By playing photographer and subject, Muholi keeps the authenticity of both roles and redefines the transaction between those roles. It is true to say that she is both (and neither) the dominant and submissive party. This is the traditional power dynamic examined through the styles she uses.

Christabel Johanson on Zanele Muholi

Somnyama Ngonyama II, Oslo, 2015 © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York.

First published: June 6, 2021

Zanele Muholi:

Hail the Dark Lioness

The Cummer Museum in Jacksonville Florida was hosting Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail The Dark Lioness), by artist Zanele Muholi. The museum is this touring exhibition’s final venue in the United States phase of international travel.

Hail The Dark Lioness sees visual artist Muholi use “their body as a canvas to confront the deeply personal politics of race and representation in the visual archive” through the 80 self-portraits offered in the viewing. Using conventional styles found in the Western traditions, such as classical painting, fashion photography and ethnographic imagery, Muholi questions the politics of identity especially around the human rights issues surrounding the black body.

As a South African, the country’s racial history lends extra gravitas to Muholi’s work. As they state, “I’m reclaiming my blackness, which I feel is continuously performed by the privileged other. My reality is that I do not mimic being Black; it is my skin, and the experience of being Black is deeply entrenched in me. Just like our ancestors, we live as Black people 365 days a year, and we should speak without fear.” Muholi employs every day materials to comment on South Africa’s past as well as international issues. The series of photographs were taken during 2012-2019 accruing a new visual codex of signs and signifiers. Modern domestic cleaning products like scouring pads and rubber gloves symbolise slavery, gender identities and cable ties evoke the image of brutality, imprisonment, exploitation.

Colorism also plays a role in the photography. Using editing to increase the contrast of Muholi’s skin tone, their complexion becomes the “interrogation of beauty, pride, desire, self-care, well-being and the many interlinked phobias and isms navigated daily such as homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, racism and sexism, to name but a few.”

Their fearless approach comes from a mission steeped with activism and a drive to “re-write a Black queer and trans visual history of South Africa for the world to know of our resistance and existence at the height of hate crimes in South Africa and beyond.”

An interesting focus of Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail The Dark Lioness) is the ethnographic pastiche based on traditional photographs. This reclamation of colonialism finds its voice initially in the title Somnyama Ngonyama which itself is an IsiZulu translation. IsiZulu is one of the languages of South Africa. The “dark lioness” pertains to Muholi but also champions the history of likening Black bodies to animals. The lion is one of the most synonymous animals of Africa and evokes power and regality. This directly challenges the stereotype of the primitive Africans.

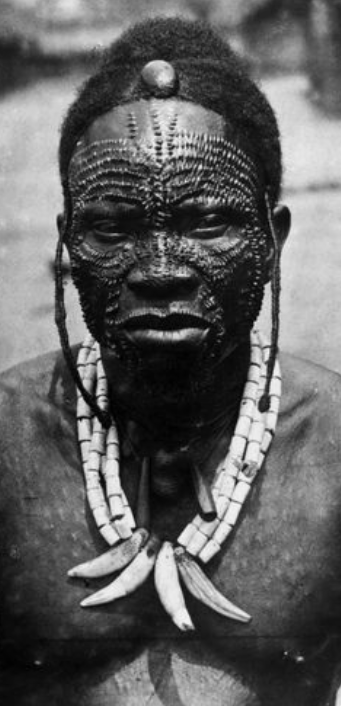

During the 19th century and 20th century (white) photographers travelled the world capturing images of exotic landscapes and people. It was a branch of Anthropology that was popular at the time. These expeditions were often to tribal communities across Asia, South America and Africa and the photographers were considered pioneers of the time. However there exists a fine balance between exploration of new cultures and the exhibitionism, exploitation of fetishism of them.

Chief of the Bapotos Tribe with facial markings. Congo, c.1919, credit E. Torday, National Geographic Society

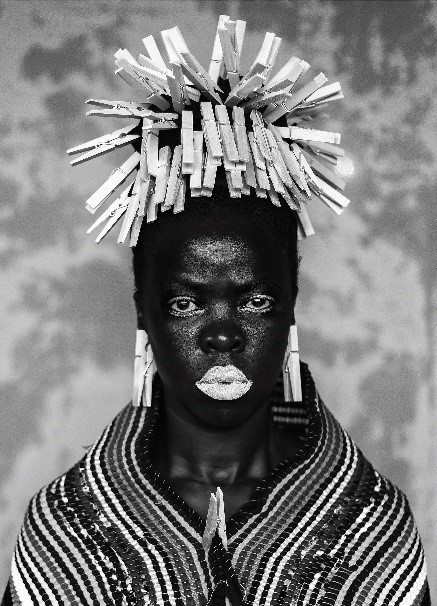

Bester I, Mayotte, 2015 © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

This is the power dynamic that Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail The Dark Lioness) revisits and challenges. In Muholi’s portrait above she brings emphasis to their lips using white lipstick which makes them appear fuller. Their body is covered with a tribal cloth. Most noticeably is the use of wooden clothes pegs on the ears and hair. Muholi’s use of these everyday objects signify contemporary issues. Perhaps here the pegs comment on gender bias and the role of women within the home. Visually the pegs also mimic the bone jewellery that many tribesmen like the Chief of the Bapotos Tribe (above photo) would adorn themselves with. What occurs is a modern contextualisation of the past; there is a sly mockery of the old ethnographic lens through the hyper stylisation Muholi uses.

Photographer Aaron Siskind once said that “photography is a way of feeling, of touching, of loving” and “what you have caught on film is captured forever” because “it remembers little things, long after you have forgotten everything.” In the case of ethnographic photography, the medium was used as a tool for the science of Anthropology. As it was primarily recording what the explorers saw – like a travelogue – and much of the social commentary that came from it was driven by people’s own biases and discrimination. Muholi’s photography poses as art which itself is politicised. Therefore the viewers, unlike audiences of ethnographic photography, are attuned to the layers of meaning from the imagery. Or at least aware that there are layers there at all. This leads to a gulf of difference in how the photographs are received. If something is presented as factual we are likely to judge based on those “facts”, yet if something is presented as artistic we open our minds to interpretation.

Herein lies the true power of the images captured by Muholi because she is consciously setting up a scene or conversation in each pose.

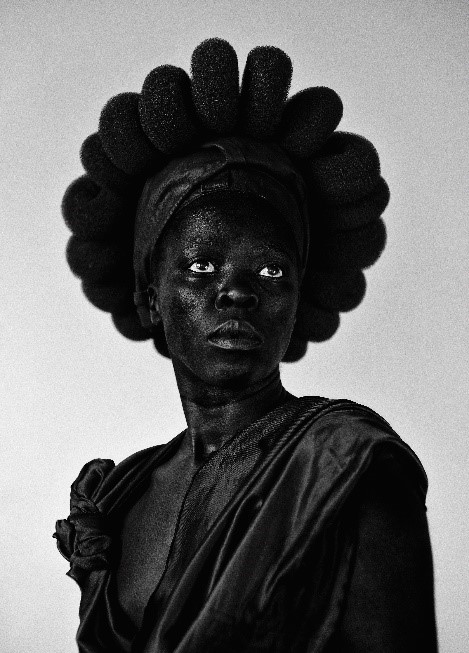

Ntozakhe II, Parktown, 2016 © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

More importantly these series of photographs teach the viewer an important lesson in discernment. It teaches critical thinking in what we see. Who created these images? Why did they do it? What do we actually see and what do we interpret? How can this be read in a wider context; whether social, political or otherwise? These are the question that feed us when we view such imagery whether we are conscious of it or not.

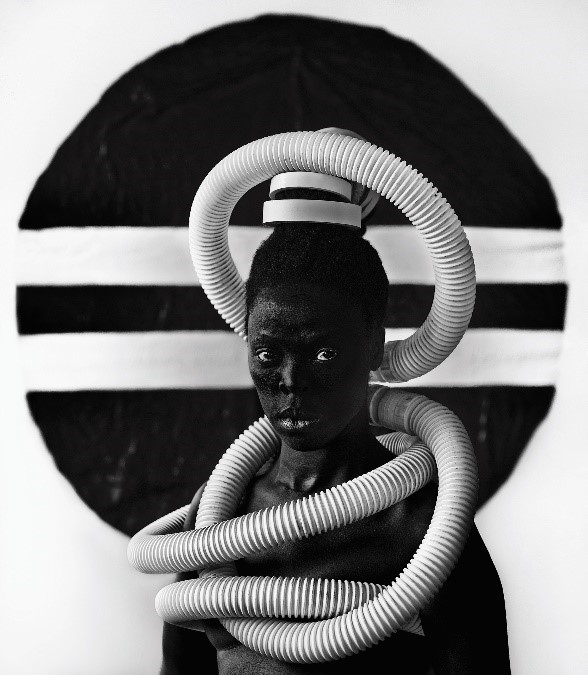

Sebenzile, Parktown, 2016 © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of Stevenson, Cape Town/Johannesburg and Yancey Richardson, New York

By playing photographer and subject, Muholi keeps the authenticity of both roles and redefines the transaction between those roles. It is true to say that she is both (and neither) the dominant and submissive party. This is the traditional power dynamic examined through the styles she uses.

As a Black body posing for these pictures she transforms herself into a living canvas and questions what piece of the subject is taken away through photography. The camera was once feared by tribal communities because it was believed it took a piece of their soul. Perhaps in some way this was true. Through the ethnographic research conducted in the last century, the West was given a glimpse of another world shown as “exotic”, “primitive” and “Black”. What piece of this collective soul was taken away by the West? The lack of understanding towards tribal norms, culture and another way of life brought much racism, stereotyping and ignorance towards black people which is still prevalent to this day. The flip side of this was the archival usage of photography. Keeping records of how people lived in the past so we can see how things have changed also resonates with elements of Muholi’s modern twist.

Ultimately photography is just a tool for its users and their intention. It can shape or warp our impressions of its subject. Somnyama Ngonyama (Hail The Dark Lioness) was designed for us to witness the varied impressions that photography can bring to us. Yet what makes it a captivating exhibition is Muholi’s ownership of the image as photographer and ownership of the image as the subject. This ultimately is what empowers the work.