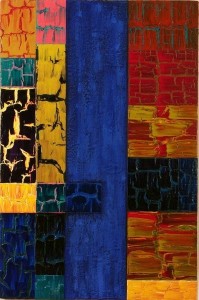

In collection of the Studio Museum in Harlem: Trane, 1969.

About:

“My art is about my experience which, by nature, makes it about other people’s experience . . . I’m trying to evoke human response. My demographic is the human arena. I hope my work is about celebration, about an affirmation of life in the face of diversity, to reaffirm that we’re human, that we’re alive, that we can celebrate existence.”[i]

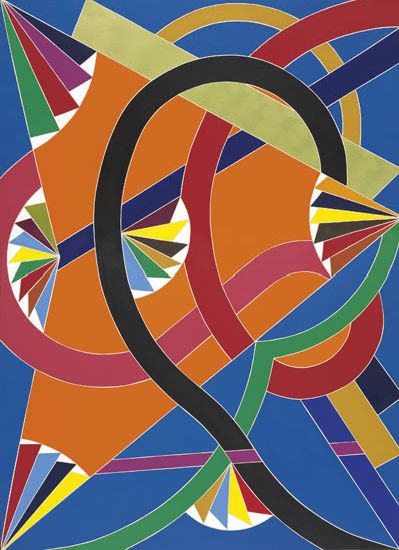

Hook and Ladder, 2000.

Born in Cross Creek, North Carolina in 1942, William T. Williams moved with his family to Jamaica, Queens at the age of four, but returned to Cross Creek frequently throughout his childhood. When he was a teenager, Williams met Jacob Lawrence and was inspired to pursue art as a profession. In 1956, he was accepted into the School of Industrial Art (now the High School of Art and Design), and he also began visiting the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art on a regular basis. Williams finished high school in 1960 and attended community college before enrolling in the BFA program at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. In 1966, Williams finished college and went on for graduate study at Yale University. He earned his MFA in 1968 and moved back to New York, settling in a loft in SoHo.

The Tattoo Artist, 1970.

When Williams began his career in the late 1960s, abstract expressionism was in decline while pop art, color field painting, and minimalism were on the rise.[ii]At the same time, artists, intellectuals, and activists were challenging the exclusionary practices of New York’s white- and male-dominated art institutions. These critiques came in multiple forms, including an approach to art that favored figural representation embedded in a politics of struggle and an assertion of identities long misrepresented by or excluded from US national culture. As an artist, Williams believed that abstraction offered him much greater creative and expressive freedom than figural representation, but he was also wary of painting that was merely about painting. Instead, he searched for a way to make abstraction represent his personal and cultural history. Williams turned to jazz as a stylistic influence that imported associations with a specifically African American contribution to art. He also employed the diamond shape as a visual motif that functioned “as a stabilizing force, a form that interacts compositionally with what’s around it. But it goes back to the quilts of my childhood, the patterns and forms I grew up with.”[iii]

Up Balls, 1971.

The synthesis between narrative and abstraction that Williams developed met with deserved success. Soon after his return to New York, Williams was included in several important 1969 exhibitions, including the Whitney Biennial and X to the Fourth Power at the newly opened Studio Museum in Harlem, a show that also featured work by Sam Gilliam and Melvin Edwards. That same year, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) purchased his Elbert Jackson, L.A.M.F. Part II (1969), which was featured in New Acquisitions. In 1971, Reese Palley Gallery, New York mounted Williams’s first solo exhibition. Every single work in the show was purchased, many by MoMA and its trustees.[iv]

Truckin, 1969.

In 1971, Williams began teaching at Brooklyn College of the City University of New York (CUNY), where he is currently a professor, and he spent a summer in residency at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, returning again in 1974, 1978, and 1979. In 1977, he participated in the Second World Festival of Black Art and African Culture, held in Lagos, Nigeria, which marked his first time in Africa. The trip, especially the movements of patterned clothing he saw on the street, had a profound effect on his art, and Williams began a series of paintings organized around “an underlying grid [that] produce[d] a pattern-like effect but retain[ed] a painterly expressionistic touch. This new body of work, like its predecessor, was created using a . . . chromatic range based predominantly on earth tones, but now added animated slashing marks and a crackled surface exposing layers of paint underneath.”[v]

Williams has continued to revise, adapt, and transform his style, and this dynamism combined with a consistent set of formal and thematic concerns, has contributed to the longevity of his luminous career. Williams has been the recipient of numerous awards and fellowships, including: a Guggenheim Fellowship (1987), the Studio Museum in Harlem Artist’s Award (1992), a National Endowment for the Arts Regional Fellowship (1994), the Brandywine Workshop’s James Van Der Zee Award for lifetime achievement in the arts (2005), the North Carolina Governors Award for the Fine Arts (2006), and the Alain Locke award from the Detroit Institute of Art. For over forty years, Williams’s work has consistently been shown throughout the United States as well as in Japan and Venezuela. Recently, in addition to multiple solo shows, he has been included in the 1999 traveling exhibition To Conserve a Legacy: American Art from Historically Black Colleges and Universities, What is Painting? (2007, MoMA), and the 2009 exhibition Tradition Redefined: The Larry and Brenda Thompson Collection of African American Art (at the David C. Driskell Center at the University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland). He is represented in several public collections, including the Fogg Museum (Harvard Art Museums) in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Menil Collection in Houston, Texas; , North Carolina State Museum; and in New York City, the Studio Museum in Harlem, Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.(text and courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery New York)

Sister of Eastern Star.

[i] William T. Williams, quoted in Hobey Echlin, “Spirit and Chance: The Informed Lifeline of William T. Williams,” Metro Times (1995). Reprinted on William T. Williams website: http://www.williamtwilliams.com/archive/articles/SpiritandChance/page2/ (Accessed February 2014).

[ii] Lowry Stokes Sims, “William T. Williams: Variations on Themes,” William T. Williams: Variations on Themes, exhibition website, David C. Driskell Center for the Study of the Visual Arts and Culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora at the University of Maryland, College Park, MD (March 31-May 28, 2010). http://www.driskellcenter.umd.edu/WilliamTWilliams/essay2-1.php (Accessed February, 2014).

[iii] Williams, quoted in Echlin.

[iv] Marsha Miro, “Master Colorist: African-American painter added new shades of meaning to 70’s art,” Detroit Free Press (1994). Reprinted on William T. Williams website: http://www.williamtwilliams.com/archive/articles/MasterColorist/page1/

[v] Marshall N. Price, “Paint and Perseverance: The Art of William T. Williams,”William T. Williams: Variations on Themes. http://www.driskellcenter.umd.edu/WilliamTWilliams/essay1-3.php (Accessed February 2014).

Michael Rosenfeld, 100 ELEVENTH AVENUE @ 19th

NEW YORK, NY 10011