The work of Nour-Eddine Jarram shows the assimilation process of an artist who is impressed by the culture of his new homeland, who wants to be influenced by it, refer to it, without ignoring or denying his Moroccan background.

Rob Perrée on the work of Nour-Eddine Jarram

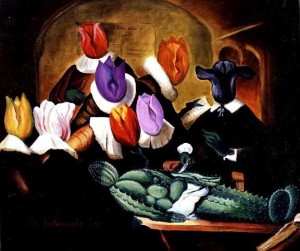

De botanische les, 1991.

Nour-Eddine Jarram

TWO WORLDS COMING TOGETHER

“In a way I imitate the ‘masters’. I make big works referring to all kind of styles and genres that were used in the history of painting in order to clear my way to the museum. What they can (do), I can do too. Their representation of white people is no less than my representation of black people. If the Prado is going to collect contemporary art I want my work to be part of that collection.”

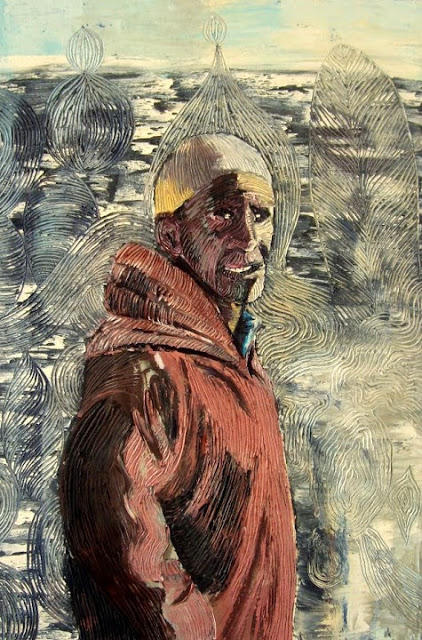

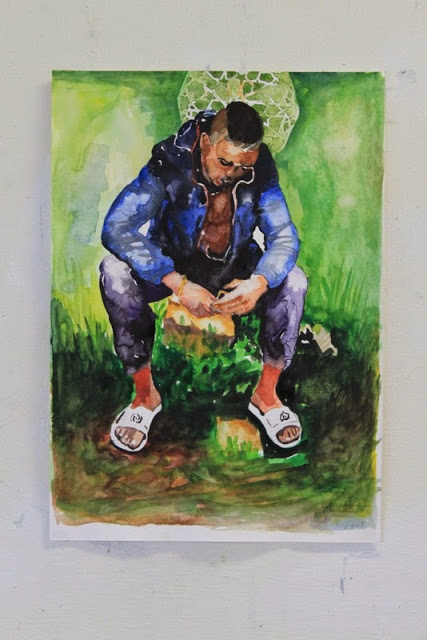

The Hitchhiker, 2014.

This is a quote of the African American artist Kerry James Marshall whom I interviewed last year in Antwerp. That quote came to mind when I visited the last exhibition of Nour-Eddine Jarram in The Hague. I got the feeling that I was stepping into the 17th century world of Jacob van Ruisdael and Jan van Goyen, famous Dutch landscape painters. The pastel works of Jarram looked like copies – at first glance – but they differed from the original. In one, all the colors were taken out. I was facing a black and a bit scary landscape. One human figure and what appeared to be an animal were added. Singletons? They were dominated by the landscape. In another work the cloudy sky was colorized with some transparent, pastel-like colors. They seem to be used to create a composition of round forms with a star in the middle. The meaning of this escaped me. In both works there was a variation on Superman built out of Arabic characters representing Islam. In the foreground, as eye catchers. Did Marshall replace the colors of Newman’s ’Who is afraid of red, yellow and blue’ by the Pan-African colors red, black and green in his version of the recognized masterpiece, Jarram puts (elements of) his culture in the ultimate cliché of Dutch-ness: a landscape with a windmill and a cloudy sky.

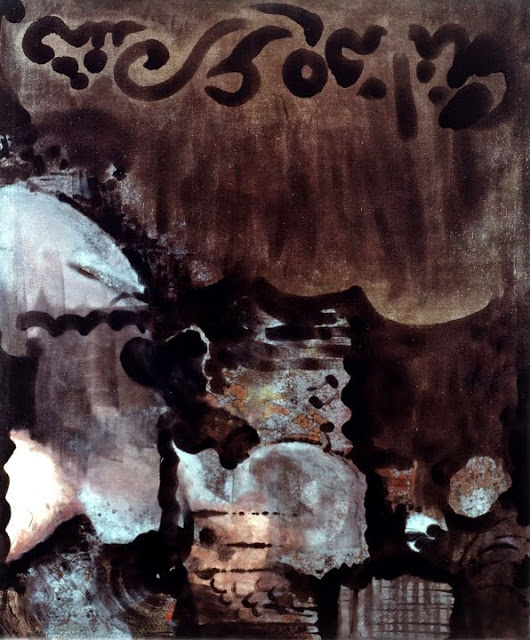

Ennemies of Art, 1985.

Does Nour-Eddine Jarram want to work himself into the Western canon, into the conventional history of art, like Marshall, or is there another reason why in his work different cultures are always mixing, mingling or contrasting?

Jarram was born in the suburbs of Casablanca, Morocco in 1956. At the Ecole des Beaux Arts he received his education in the traditional skills of his future profession. Useful, but not very exciting or stimulating. Because it was easy to get a scholarship to study abroad, he decided in 1979 to apply for the academy AKI in Enschede, the Netherlands. He was accepted. The contrast couldn’t be bigger.The AKI at that time was an academy with few strict rules. You could do whatever you wanted to do, you could attend class whenever you wanted to come. Teachers were giving input only if you asked for assistance. They stimulated you if you were open for it. For Jarram it must have been a double culture shock: living in a country that was very different from his motherland and studying under circumstances that were in no way comparable to the ones that were considered normal at home. He seemed to manage, but in his work you could see that his struggle was bigger than it seemed to be at first site. After he finished the AKI it did not take him long to be represented by a gallery. A very hip one. ‘The Living Room’ was showing work of upcoming artists with international potency. It was the most talked-about Dutch gallery in the eighties. In fact, Nour-Eddine Jarram made a dream start.

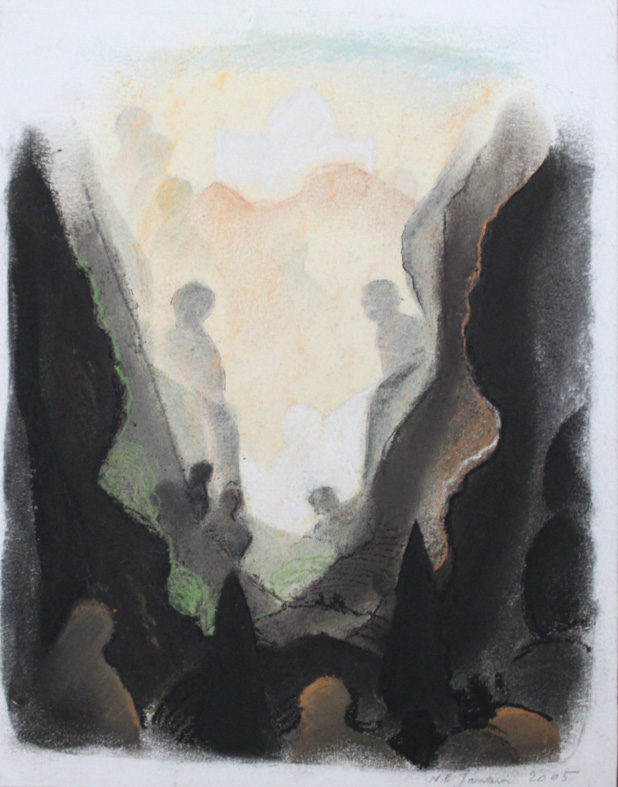

Untitled, 2010.

From the beginning on pastels and paintings were his mediums. Perhaps as a consequence of his traditional but solid education at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Casablanca, Jarram is always experimenting with the possibilities of the materials he is using: the kind of paper; the kind of paint; the kind of linen; the effect of paint brushes, hair brushes, combs and spatulas; the size of his paintings and pastels; the mixing of paints; the tactility of the skin of a painting; the result of light in relation to space; the effect of stillness versus movement; the relation between color and content etc. These experiments lead to an oeuvre that, apart from the content, always knows how to surprise, how to trigger the viewer to pay attention.

Portret van een onbekende kunstenaar, 1985.

The depiction of human beings and animals is problematic in Islamic culture. The Hadith does not allow it, the Koran itself is less strict about this issue. The content of many works of Jarram has to do with the controversy between Western (Christian) culture and Islamic culture. For him assimilating means finding a way to gain access to the culture of his new homeland without ignoring or denying the culture in which he grew up. That struggle becomes visible in his drawings and paintings. (Nour6) They often focus on forms – geometric patterns or calligraphic signs – and spaces. They look like stages with side-scenes where the actors are missing or just left the stage. There is a more or less clear foreground – lively and mobile – and a mysterious background, a background that often draws you in because of the ingenious use of light, Rembrandtesque light. If there are human beings present than they are abstracted, they are suggestions of human beings. For a Western viewer all these elements create mystery. What is going on there? Do I see a gate to another world that is not recognizable immediately? Is it pure fantasy or is there a reality behind it? Is it just a game of light and darkness, of forms and colors in a layered space?

Rising from the Roots, 1988.

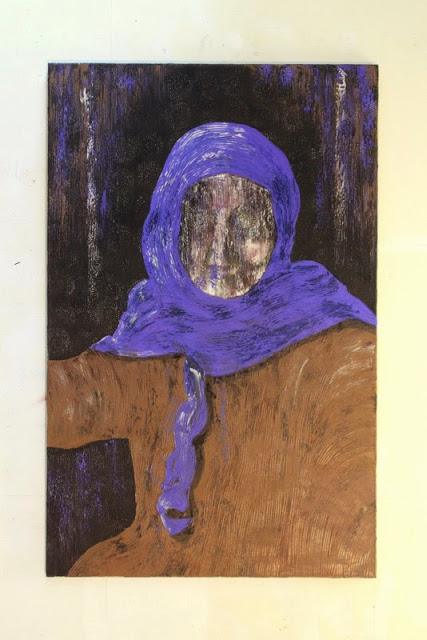

Although there were always works with people in it – without faces , but also with faces – in his recent works they show up on a regular basis. Jarram has lived in the Netherlands much longer than he lived in Morocco. He has distanced himself more from his former culture and the relatives who represented that culture. A couple of years ago his mother died. He honored her with three paintings. Two are faceless or almost faceless, the third one is a portrait that fits in a long, Western, expressionistic tradition. Only the circular signs on her face and on the background could be seen as reference to his Islamic culture.

La Sacrifiée, 2010.

La Sacrifiée, 2010.

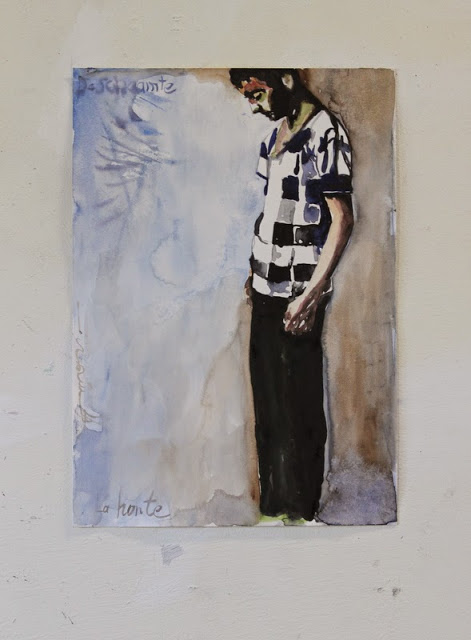

With his recent paintings and pastels based on the landscapes of Van Ruisdael and Van Goyen, though also inspired by the scenic view from his new studio, he seems to confirm that his assimilation process has come to an end. More so with his recent watercolors that he did not show, did not want to show yet. I saw them in his studio when I visited him. He talked about it as if they were not more than sketches or doodles. To fill the gap which always shows up after an exhibition. In a colorful, expressionistic, often vulnerable, loose way they portray young Moroccans, shamefaced but also proud, eyeing or looking away. More than before, as far as I know, Jarram is inspired by the political situation of the moment in which his original culture is under fire, in which you are being forced to choose or to commit to. The mixed feelings of the men he portrays and the vulnerable style he uses shows that he wants to deliver a nuanced contribution to the discussion. Perhaps these water colors are missing the mystery, the power of the unknown that characterizes many of his older works, instead they are more moving and more confrontational. An interesting development.

Untitled, 2015.

La Honte, 2015.

Kerry James Marshall’s knocking on the door of the canonized art history is a political choice. The work of Nour-Eddine Jarram shows the assimilation process of an artist who is impressed by the culture of his new homeland, who wants to be influenced by it, refer to it, without ignoring or denying his Moroccan background. It is ironic that his most recent work reacts on the political circumstances in which Islam is at the center of an international, emotional discussion in a style he could not have been used 30 years ago, when he started his artistic career in The Netherlands.