Street art has been a means of education, awareness raising, increasing knowledge and moulding public attitudes; which encourage constructive behaviours that can lead to a peaceful co-existence, mutual respect, common goals and aspirations.

Craig Halliday on the importance of street art.

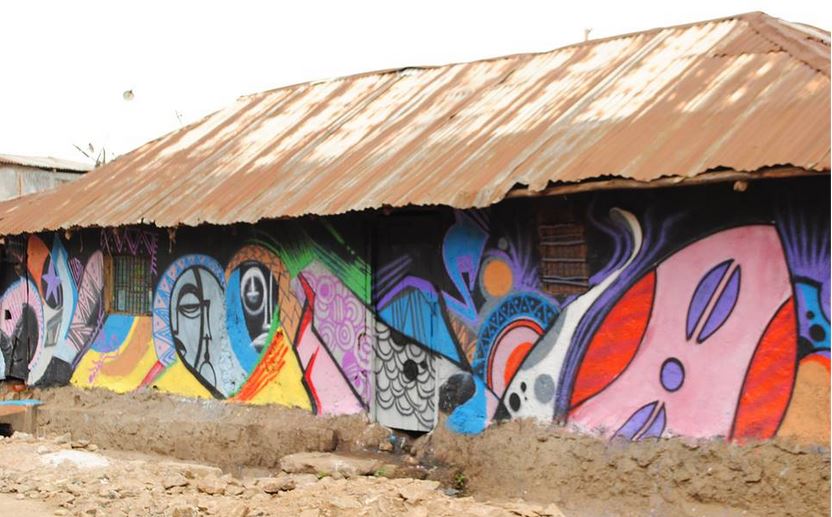

HRI Talking Walls Project transforming Korogocho.

Taking art to the people: public space, cohesion and protest

Outside of Nairobi’s conventional art spaces, such as galleries and museums, street art is being used to change the city’s environment and (re)create its socio-political spaces. Street artists are engaging in activism and community development in unique ways, extending the remit of arts transformative abilities.

Placing visual art in Nairobi’s open spaces extends possibilities for social transformation. Street art has been used globally for publicising protests and resistance movements, while creating public socio-political spaces of engagement. I refer to street art as the art forms of wall painting, murals and graffiti in public spaces, or spaces accessible to everyday Kenyans. Public spaces are recognised as all places publicly owned or of public use, accessible and enjoyable by all, for free and without profit motive; which consist of streets, open spaces and public facilities.(1) It is here where people meet, interact, form collective memories, identities, meanings and construct themselves, city life and space. These areas are important for improving community cohesion, and contributing to the overall quality of life and civic identity. However increased urbanisation, population growth, land grabbing, insecurity, poor planning and lack of resources has put public space at risk in Nairobi. The following case studies will demonstrate how organisations and artists, through the use of street art, are (re)claiming public space, shaping identities and opinions, being a voice of the people and changing the urban landscape.

(Re)Claiming public space and strengthening community cohesion and peace

Art has been used to redefine neighbourhoods in Nairobi, particularly informal settlements. Here open space is all too often absent; resulting in public space mainly consisting of streets, a platform where urban life unfolds daily. Land allocated to streets in Nairobi is just 11.5% however this drops hugely for informal settlements; for example 3% in Kibera.

Given that 47% of people’s main form of transport in Nairobi is walking streets become the spine of all communities, connecting the city, playing a prominent role in shaping its culture and history. However, in informal settlements, these spaces are often seen as isolated entities, separated from the larger city network, dangerous and insecure. Youth, who make up the majority of inhabitants in these communities, are regularly viewed as perpetrators of crime, vandals, idlers or disturbers of peace; and are often left out of any community planning processes and activities. This may leave residents without a sense of belonging; resulting in the space’s potential losing value and importance.

However, organisations working in the poor settlements of Korogocho, Kariobangi, Kibera and Mathare have been using street art; while actively engaging their communities (particularly youth) as resources in urban transformation; in order to (re)claim the ‘street’ as public space, while strengthening community cohesion and fostering peace.

‘Sauti Ya Mtaa’ (SYM) uses ‘data murals’ to visually display relevant and localised information enabling communities to become better informed on issues pertinent to their lives. In Mathare SYM discussed issues of insecurity, extra judicial killings, mob justice, poor policing and lack of accountability; thus creating a space which can be used as a resource and outlet to empower community members to engage in dialogue to make data-driven arguments with local authorities.

‘Hope Raisers Initiative’ (HRI) uses street art to aesthetically transform the streets of Korogocho through messages of hope and peace. Since 2014 over 1.5km of surfaces in public spaces have been painted. (2) Daniel Onyango, the director of HRI, says that “The idea is to beautify and make our streets better… We are encouraging people to express themselves, which is a democratic right”.

Both SYM and HRI projects inspire young artists in these neighbourhoods. Kerosh, a Kenyan graffiti artists, who works with both SYM and HRI says: “The community appreciate what we are doing. We involve them, consult them and they help us come up with ideas for the artworks, that way we see so much interaction, especially with the youth. The youth have been neglected in every part of planning or every part of making the community their own. When they have an avenue where they can be involved in creating the change they want, which also engages them with a form of self-expression, then it gives them a sense of responsibility and also a sense of adding value to their community. It has become their way of saying that they also belong in this space, because generally they are left out of these decisions and activities.”

The use of street art as a means to foster peace and social cohesion has been used across Nairobi.(3) The “Kibera Walls for Peace” project, implemented in 2013 by Kibera Hamlets (KH), local children, American artist Joel Bergner and Kenyan graffiti artists, used street art to promote peace, understanding and cooperation between groups within Kibera; contributing towards a large peace narrative across all media platforms in the run up to Kenya’s 2013 elections. Youth (aged 14-24) from different backgrounds participated in peace building and public art workshops; which informed the creation of seven public murals (and the painting of a commuter train) in Kibera’s different ethnic and religious communities. John Adoli, director of KH, says: “People find the murals attractive and when people are attracted to the murals they get the message. The murals were placed at strategic points where many people pass so the messages were shared among communities quickly. Before, these spaces were not appreciated or taken care of, people would urinate or rubbish there. They now use these places to gather, sit, talk or do business. They are spots which are now valued and appreciated.”

The murals used a mixture of imagery and text (coming from the youth and community consultations) covering ‘tribalism’, corruption, unity, peace and reconciliation. Some imagery and text was straight to the point; such as “Kabila lango ni m’Kenya” (My tribe is Kenya), “Amani ni Kusameheana” (Peace is Forgiveness), “Vijana Tuishi kwa amani” (Youth we live for peace), and “Tuwache Ukabila, Tuwache Ubaguzi, Tuishi Kwa Amani” (down with tribalism, down with prejudice, up with peace). The use of characters in other murals offered a less confrontational means of communicating sensitive or unspoken topics in society. The project received wide media coverage (4) and visiting Kibera in 2015 the majority of murals were still present. Speaking to John, he says murals as a medium of communication were chosen because “Murals bring people together, raise awareness and give people time to reflect on what the art is communicating. This isn’t always achieved verbally, especially between a young and old person and those of different genders or tribes. However, murals do not have an identity behind them, they are neutral and anonymous.”

The use of street art has transformed once neglected sites into spaces of greater public use which feel valued, are enjoyed and provide a sense of ownership and pride for residents. In Korogocho, a neighbourhood where few people visited, Kersoh says people now come from all over Nairobi to see the graffiti, especially musicians who film their music videos there. The involvement of youth in planning and decision making activities regarding the visual transformation of their community’s spaces shines a positive light on their potential as agents of change; while also inspiring new generations into art, social transformation and ensuring their voices are heard. Street art has also been transformational through educational and awareness raising means. Renowned graffiti artist Bankslave, who worked with SYM and KH, claims graffiti speaks to youth like no other visual art. The messages communicated in street art, and activities surrounding these, build ideas of citizenship and community cohesion, which can generate urban and individual transformation. Together these actions of (re)claiming public space can be truly transformational; by strengthening communities through the involvement and coming together of a range of stakeholders, creating a shared view and responsibility through inclusive practices, changing perceptions, views and responsibility.

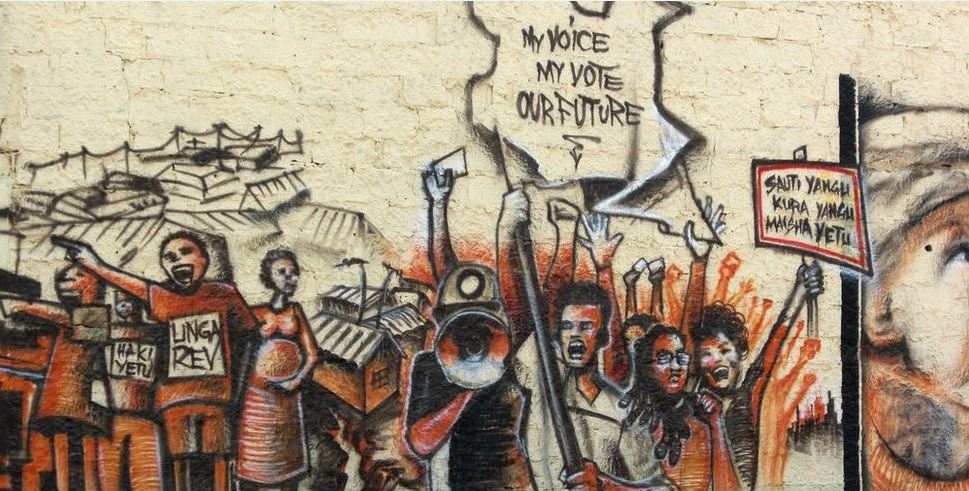

Voicing dissent and protest

The use of street art, specifically graffiti, has a history of being a means and medium to voice dissent and protest. The very existence of this art form, which is often illegal, is itself a clear symbol of resistance. Placing street art in unexpected or prohibited places can stimulate reflection and social action. The organisation PAWA 254 (5) has proactively used street art in its campaigns and protests – raising critical awareness around issues of corruption, land grabbing, oppression, brutality, injustice electoral violence, tribalism and governance issues.

One popular campaign led by Boniface Mwangi and Kenya’s top graffiti artists (6) was ‘MaVulture’ which through the use of street art, drew attention to endemic issues of bad governance, corruption, and abuse of office perpetrated by the political class.

Imagery used centred on a vulture; satirically representing the scavenging political class feeding on the weak. Other imagery and text (some contributed online by Kenyans) highlighted corruption, ‘tribalism’, tax evasion, internally displaced people, post-election violence, land grabbing, and political assassinations; relating to how MPs have been ‘screwing Kenya since 1963’. Out of 41 locations where the graffiti murals were painted some were illegal. Mwangi says “Some laws have to be broken for people to be heard”.Despite Kenya’s ‘partly free’ press status and reputation for vibrant and critical reporting there is a feeling among Kenyans that some discussions are still not taking place; Mwangi feels it is his and PAWA 254’s responsibility to do this, saying “If the mainstream media doesn’t tell this story, we have to tell it.” Therefore, these artworks broke a conspiracy of silence. Asked why he felt visual art was an appropriate medium to communicate these issues Mwangi said: “Art is very complex… but art is very simple at the same time as a tool for communication. The power of art makes you stop and think, makes you stop and feel emotional about it…. Art goes beyond gender, age, social background, class, race, sexual orientation, because art drives life, without art there is no life.”

The artworks present a clear challenge to the hegemonic and their (mis)practices; with all political parties coming under attack no one is favoured. The campaign elicited huge public engagement and was generally well received by society. Unsurprisingly there was uproar among parliamentarians; which perhaps more so than the art works illegality motivated its removal by local authorities. However, in a viral age these artworks were quickly reported by local and international media (7) and were carried widely across independent blogs and social media; creating much discussion and debate amongst Kenyans and the international community; contributing to Kenya’s public sphere. For example the hashtag #LetMwangiDraw and #KenyaNiKwetu started trending as support for the project and freedom of expression grew.(8) Ironic as one of the murals read ‘middle class Kenyans, get off Facebook and Twitter and do something positive offline’.

While it is difficult to truly understand the impact of this project Mwangi says “What we are doing is planting a lot of seeds, some will germinate and some will die, but eventually we are going to get a harvest.” The metaphor of vulture continues to be used. It was also appropriated in a number of popular music videos which advocated for peace and how everyday Kenyans hold the power to change the status quo.(9)

This campaign, through its use of art and straight to the point messages, was described as “heralding a new dawn in political activism”. The imagery and accompanying text in the campaign are far from the more subtle and questioning works of studio artists. Mwangi explains his reasoning for this approach: “We are trying to shock you so that you can actually think about what we are trying to do. We are provoking you so the provocative and shocking is our intent. We are not here to sooth your emotions or sooth your ego, or make you feel comfortable. We want our work to make you feel uncomfortable to do something…..We shade off the complexity in art, we don’t want it to be complex….we want to give you the meaning. For example we say pigs are greedy, these guys [MPs] are pigs, that’s why we give you pigs. The vulture takes advantage of the weak, the oppressed. So the vulture represents MPs. It is direct there is no double meaning there.”

The other artists involved in this campaign also see art’s role in activism. The graffiti artists Uhuru B says “We have to wake people’s minds … If it’s not us, it won’t be done”. Smokilla, another graffiti artists says “We want to bring about a ballot revolution …. We want change. We are a vessel that gives a voice from the people,” whilst the artists Swift 9 calls for a “political awakening among us, the majority”. The graffiti artists involved in this project describe their actions as ‘Artivism’ (a term popularised by PAWA 254 which is the coming together of art and activism). However, there is a concern that artists may well allow their creativity and point of view to be restricted by organisational agendas. This doesn’t detract from the agency of visual art in communicating with society but does pose questions as to the role of some artists in such campaigns and projects. What is clear nevertheless is how this and similar projects contribute to freedom of expression through creative means that openly challenge the state or conventional narratives which is a key value of democracy.

Summary

Placing art into communities exposes segments of society to elements of contemporary art, which they otherwise may not encounter, and also opens community dialogue into the role which the arts can play in positive social transformation. This has been seen through making spaces more public, valued and endowing them with a positive identity. Street art has been a means of education, awareness raising, increasing knowledge and moulding public attitudes; which encourage constructive behaviours that can lead to a peaceful co-existence, mutual respect, common goals and aspirations. These have been used for the purpose of social cohesion and peace building. In addition ideological messages in street art have challenged the dominant hegemony of the Kenyan political and ruling class. These actions and practices broaden the idea of citizenship, which resort to the very basic democratic values and the freedom of expression.

The involvement of young people in these projects (engaged directly and communicatively through the medium of graffiti and workshops) open possibilities to individuals and groups who previously may have be unaware of their ability to create social change, but now may choose to lead a life of activism or the desire to improve one’s community. Furthermore a young generation of Nairobians, particularly those from slum communities, have learnt how to express themselves through art rather than anti-social acts, violence or risky behaviours.

1. This is a widely used description public space and one that is adopted by the Charter of Public Space

2. This has been part of the talking walls project started in 2014 and the seven day festival ‘Koch Fest’, held in August 2015

3. Examples of this include the work of artist Solo 7 who spread hundreds if not thousands of simple messages declaring ‘Peace Wanted Alive’ and ‘Keep Peace’ on all surfaces of Kibera and other localities across Nairobi during and after the 2007 post-election violence. Later came projects such as the ‘Amani Lazima’ (Peace is a must) campaign by Sarakasi Trust; and the ‘Art4Peace’ project run by Maasai Mbili with local children whom together transformed spaces such as the walls of Kibera Drive and burnt out ruins; using art as a means of therapy for traumatised children and to physically and symbolically engender a positive environment promoting concepts of peace and reconciliation between fractured groups within Kibera slum.

4. Media coverage came from Arise (http://www.arise.tv/latest/arise-news-27-feb-1183 from minute 8:40-11:12), BBC (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-21616945#), National Public Radio (http://www.npr.org/2013/02/19/171916072/kenyas-graffiti-train-seeks-to-promote-a-peaceful-election), CNN (http://ireport.cnn.com/docs/DOC-934024) and Reuters (http://www.english.rfi.fr/africa/20130227-kibera-fears-repetition-kenyan-election-violence).

5. PAWA 254 is a space promoting the use of art for social change. It is based in State House Crescent, with two mobile hubs in Kariobangi and Kibera. Established in 2011 it claims to have trained 100,000 artists through workshops and trainings, held 5 peaceful demonstrations calling attention to various social issues, hosted weekly debates and discussions on current social issues and sees an average of 400 artists using the space weekly

6. These artists included Uhuru B, Swift 9, Smokillah and Bankslave, while some other graffiti artists chose to remain anonymous

7. Media outlets included BBC, Daily Nation, Aljazeera, The Guardian, TED, NTV Kenya, Capital FM Kenya, The Star Kenya, Capital Talk, Reuters Africa, CNN. A digital library containing links to many of these reports can be found on the ‘KenyaniKwetu’ Storify website at https://storify.com/knk/political-graffiti-in-kenya

8. This was especially the case when Mwangi was summoned to a local police station for questioning over his actions and involvement in the campaign (during which time he was the only person who declared his involvement, while other artists remained anonymous)

9. The song ‘Matpeli’ by the artist Jaguar spoke of the deceitfulness of the political cartel and how “you and me” have the ability to change the status quo. The music video, which was published on 12th August 2012 and has over 91,000 views, can be watched on Youtube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmGzA7iHSYE the music video of Kenyan hip hop artist Juliani’s song titled ‘Voters vs Vultures’, which features Boniface Mwanigi, and ends with an energetic crowd shouting “People, Power, Possibilities” – advocating for peaceful elections that will provide Kenya with trustworthy leaders. The music video, which was published on 13th February 2013 and has over 29,000 views, can be watched on Youtube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7DMMlpIrIIw

Craig Halliday is pursuing a PhD in the role of visual art in Kenya’s democratisation. Prior to this Craig completed a MA in African Studies, MSc in International Development and has worked and lived in Kenya, Myanmar, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Zambia. When not working or studying Craig is a keen photographer and has a painting studio in Norwich, UK, where he lives.