“Zanele Muholi not only wants black lesbians and transgender individuals to be portrayed in a more honest and respectful way, her photos are also a visual protest against the sexual assaults and violence directed towards the LGBT community. On many occasions she has made it clear that she is more than a photographer, she wants to be known as an activist.”

Rob Perrée on South African Zanele Muholi.

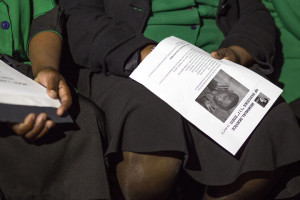

Duduzile Zozo’s Funeral, Thokoza, July 2013.

ZANELE MUHOLI: THERE WERE NO IMAGES OF PEOPLE LIKE ME.

“At the time I was working for ‘Behind the Mask’ (a communication initiative focusing on the rights and affairs of lesbian, gay, bi- and transgender (LGBT) people in Africa, launched in 2000, (rmp)) as a reporter, and I was really, really frustrated because I realized that there were no images of people like me. There were no real images of black lesbians. Even though there were some images that were there for people to see what a black lesbian looked like in my space, they were not quite representative as to how I wanted people to perceive black lesbians in South-Africa. So I took it upon myself to make sure that we were present in historical documents in my country. So much change had taken place since 1994 and I could not help but think, how is it, that you still do not see yourself in this place.”

This quote of Zanele Muholi (Umlazi, Durban, 1972) explains clearly why she ones started with her ongoing photography project. The recently published book – ‘Faces + Phases, 2006 – 2014’ – proves how amazing this project worked out.

Simphiwe Mbatha, August House, Johannesburg, 2012.

Simphiwe Mbatha, August House, Johannesburg, 2012.

Muholi was born in Umlazi, a township on the east coast of KwaZulu-Natal. Her mother was a maid, a domestic worker. The Muholi’s were a family of five kids. To keep a family like that together under Apartheid and the difficult living circumstances that went with that system, was a big deal. It disturbed her already as a girl that photos of maids like her mother never showed the reality of who and what they really are. She missed the representation of their heroism, their courage, and their determination.

The difference between reality and the representation of the reality would become an enduring theme of her work.

Collen Mfazwe, Women’s Gaol, Constitution Hill, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, 2013.

Collen Mfazwe, Women’s Gaol, Constitution Hill, Braamfontein, Johannesburg, 2013.

Muholi was admitted to the Market Photo Workshop, a training institution founded in 1989 by the renowned David Goldblatt for young photographers who otherwise don’t have access to photography. Although she wasn’t very fond of academia she continued her education at Ryerson University. “I needed to get myself the equipment to tell my story and defend it when it comes under attack.”

Nelson Mandela was released from prison in 1990. Apartheid was officially abolished two years later. Then in 1994 the first democratic elections took place. In 1996 South Africa issued a new constitution in which the human rights of the people were guaranteed. Compared to the constitutions of other African countries the one in South Africa can be called progressive. In 2006 the law that made gay marriage possible came into force. It was an unique law because at that time only a few countries had legalized gay marriage. In Africa it is still the only country.

Chairman Carrol, Park Town, Johannesburg 2013.

Chairman Carrol, Park Town, Johannesburg 2013.

These facts presume an almost ideal society. The reality tells a different story, especially for the LGBT community. Homophobia is wide spread. Also among people who represent official (governmental) institutions like the police, health care institutions, city offices, and, not to forget, the churches, anti – gay sentiment is pronounced. In 2009 the minister of culture walked out of an exhibition with photos by Zanele Muholi because in her eyes the work was “immoral” and “pornographic”. Violence against black lesbians and transgender men is not incidental, in that society, it is a frequent occurrence. The rates of sexual assault are high. Many lesbians in South Africa have been victims of a so called ‘corrective rape’, rape perpetrated to cure them of their sexual orientation.

Zanele Muholi not only wants black lesbians and transgender individuals to be portrayed in a more honest and respectful way, her photos are also a visual protest against the sexual assaults and violence directed towards the LGBT community. On many occasions she has made it clear that she is more than a photographer, she wants to be known as an activist. “How does (being a photographer) validate and remind me of my agenda? Instead of being someone who is just taking an image of Pam, my friend, I am also highlighting that such women are alive, live and love others and aspire to the same things heterosexual people aspire to while they have the capacity to contribute and actually do contribute to our society as a whole. How does being simply a photographer keep that permanent? I am an activist first, being a photographer allows me a greater and more influential audience (…).”

Nosiphiwo Kulati, Orlando, Soweto, Johannesburg, 2013.

Nosiphiwo Kulati, Orlando, Soweto, Johannesburg, 2013.

I believe what she says, but she underestimates the quality of her work by putting it that way. Her work is not just a catalogue of portraits of black lesbians and transgender individuals. It is not just a collection of passport photos or an ordinary archive. It is much more and, because it is more, the photos have the effect she is trying to create. Almost all her ‘models’ are women that she knows. There is a relationship. There is a sort of friendship, a mutual interest in each other. Often the photo that hangs on the wall of a gallery or a museum is not the first image she made of that particular person. All of her photos show an intimacy. They show vulnerability because ‘the model’ was not afraid anymore to really show herself. The images show pride because ‘the model’ felt safe. One of her models put these sentiments into her words: “I found it difficult to look at the photo. It was taken two days before a very painful transition in my life. When I looked at that picture, it was almost unbearable to look at the sadness in my eyes.” That encapsulates the unique quality of Muholi’s work, that’s why her message has such resonance. As a viewer you feel that you are viewing more than simply and image. You feel the intent and the emotion behind the image.

Of Love & Loss, installation view, 2014.

Of Love & Loss, installation view, 2014.

In a number of recent projects not only does the intimacy seems to be stronger, but she also manages to illustrate the schizophrenic situation in South-Africa by juxtaposing love and death, joy and pain. In ‘Of Love & Loss’ – an exhibition at the Stevenson Gallery in Johannesburg in March 2014 – she presented an installation and a number of photo series. In the middle of a darkened room she places a transparent coffin with flowers on top and a portrait at the back. When you enter the room it feels like you are part of the ceremony, as if you are a friend or a family member. You want to look at everything and at the same time you are afraid to look. You are curious and at the same time you feel ashamed to be curious. With the transparency of the coffin Muholi refers to openness of these events: funerals of the victims of violence get a lot of media attention. In spite of that fact, the violence against lesbians and transgender people goes on and it is still impossible to openly talk about lovemaking between lesbians and gay men. In the same exhibition she juxtaposes photos of lesbian weddings and lesbian funerals. At first sight these photos seem to be simply documentary, plain registrations of events. In reality, that is not the case. A number of the images focus in detail on the crucial moments and aspects of these events: the tears, the rings, the fun, the high heels, the kiss, the acts of protest, the burning candles, the remarks of the minister etc. By focusing on these details she creates intimacy. Intimacy is also the key concept for the ‘ZaVa’ series. They show two women displaying their love for each other, in vague, somewhat blurry, black and white images. They are touching as well as exciting. The compositional beauty of the photos makes them a precious present, a celebration of love, love that is legalized by law but brutalized by the population.

ZaVa I, Paris, 2013.

ZaVa I, Paris, 2013.

In 2012 Zanele Muholi was invited to present her ‘Faces + Phases’ series at the Documenta 13 in Kassel, the best platform you can get as an artist, the culmination of an artistic career. For her it was all the more important because she doesn’t want to work for just a queer audience “To have all of these people coming into this space and appreciating us means a lot.”

There is another reason why she wants to go on with her ‘Faces + Phases’ project. For her it is also important to archive African-ness. “We live in a time when we don’t know what is African anymore. Who is African and who decides what is African? We, as black communities, have not had our histories documented properly.”

Ayanda & Nhlanhla Moremi’s Wedding, Kwanele Park, Katlehong, November, 2013.

Ayanda & Nhlanhla Moremi’s Wedding, Kwanele Park, Katlehong, November, 2013.

Courtesy Stevenson Gallery Cape Town, Johannesburg.

‘Faces + Phases. 2006-2014’

Hardcover: 368 pages

Publisher: Steidl (November 30, 2014)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 3869308079

ISBN-13: 978-3869308074

Hardcover $40,90.