She depicts Goddesses, monsters, and animals that incorporate a new and subversive mythology. She facilitates a transgression and in turn makes the viewer an accomplice in decoding imagery. If the female body does carry the language and nuances of culture, there is something conspiratorial in taking imagery— subverting it—and creating a new language.

Hannah Snyder on the work of Wangechi Mutu.

Eye Spy, 2011.

First published: November 10, 2019

WANGECHI MUTU

On Goddesses, monsters and animals

“Females carry the marks, language and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.”

Merrily Kerr, Wangechi Mutu’s Extreme Makeovers, Art On Paper, Vol.8, No. 6, July/August 2004. posted on: http://www.akrylic.com/contemporary_art_article73.htm

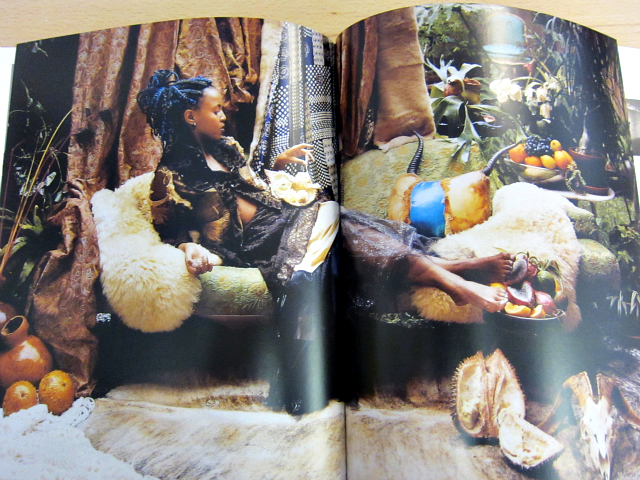

1. Portrait of The Artist, Portrait of Wangechi Mutu (2008), by Kathryn Parker Almanas, in “A Shady Promise”

In Portrait of The Artist (figure 1), Wangechi Mutu reclines on her side like so many female subjects before her. She gazes down at an open fruit on her lap, her hand hovering above it, carefully poised. Her surroundings are tapestries, furs and fruits, and she is in what looks like a rain forest, although an interview with Deb Willis tells us the background is only a projection set up in her backyard. The setting and props allude to the exoticism and Orientalism at play. She self-ascribes the portrait as ‘tongue-in-cheek,’ employing a subversive humor that confronts being African, being a woman: unique spaces in their own rights, but each often leading to being fetishized and seen as ‘the other.’

Mutu’s photomontages take ethnographic history into consideration, creating contemporary fictions by piecing together fashion magazines, pornography, documentary photography, and medical catalogues. Thematically, Mutu tends to represent women and woman-like creatures. She talks about her Catholic school upbringing as the origin of her interest in depicting women figures: “In some ways a lot of my singular female images are always a dedication to reworking that ultimately unfathomably impossible ideal of the Madonna.”

The women are in various states of birthing, healing and eating. Many are depicted squatting, close to the ground adhering to the type-cast of African primitivization, while other characters have their mouths wide open preparing to engulf: on the verge of eating everything (like the title of Mutu’s video for artist Santigold). Their beauty has been described as dystopic, and they seem to propose an alternate mythology.

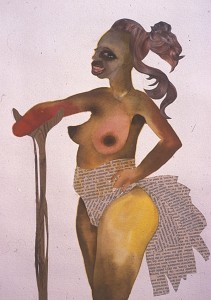

2. Pin-Up 7, 2001, mixed media on paper, 13 x 10 inches

In the Pin-Ups Series, Mutu’s use of collage and watercolor create women who smile seductively like the many pin-ups before them. They are in two sets of twelve, mimicking a calendar format. Mutu’s Pin-Ups are not the conventional calendar girls, but are inspired by the survivors in Sierra Leone. They have amputated limbs, and are maimed and disfigured (figure 2). There is something beautiful and confrontational about these women, asserting their sexuality with bodies that are both wounded and aggressively healing in fragile watercolor and heavy collage. They support themselves on canes and pegged legs and they all make eye contact with the viewer, presupposing questions of ‘the gaze’ and employing agency.

Surrealist and French intellectual George Bataille argued that the images in “The Deviations of Nature” confront the idea that all individual forms differ from the common ideal and are therefore, in some degree monstrous.” The 1775 catalogue, “The Deviations of Nature” illustrates Siamese twins, children with no limbs, and other scientific anomalies. Like Mutu’s Pin-Ups, Bataille subverts the notion of ‘the ideal’ and highlights the seductive horror of what is deemed monstrous.

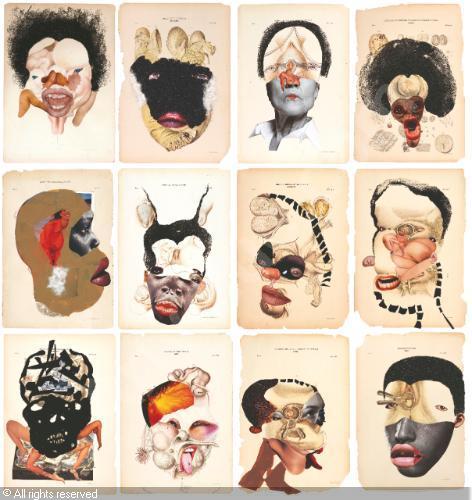

4. Histology of the Different Classes of Uterine Tumours, 2004,

Glitter, ink, collage on found medical illustration paper

46 x 31cm

In Histology of Different Classes of Uterine Tumors, Mutu explores the monstrous as a non-ideal further, by taking diagrams from epidemiological books and fashion magazine clippings to make ludicrous faces. Mutu strays from conventional female shapes and references, and while the images are undeniably female, they are more like cellular aliens you would find under a microscope in a science fiction movie. One image combines the furry eyes of a mammal, cherry red, sex-doll shaped lips, and a 70s style afro (figure 4), all this imposed on a textbook page. Mutu self-ascribes as an “irresponsible anthropologist and irrational scientist” and Histology is another approach at defining and understanding cultural symbols by merging the internal female organs with the external.

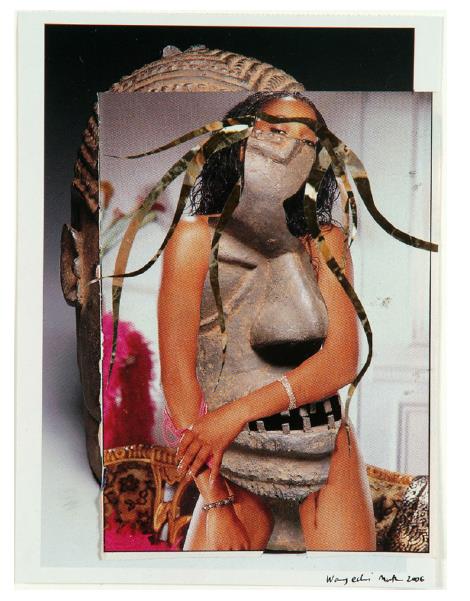

Throughout her career, Mutu continues to rework ideas of identity. The Ark Collection, which was made around the same time as Histology follows a familiar form, pornographic images are sliced together with images of African women that look out of the pages of a National Geographic. They mask one another, pornographic and ethnographic codes coming together to create a familiar language of foreign seductiveness.

In her talk for Gender Studies Feminist Technologies at The New School Mutu explained all the African images were archived from two white, women photographers who traveled East Africa. Titles like Afar Girl and Rashaida Woman Dancing purposefully point to a documentary affect and the fictive nature of Western representations of Africa.

5. Wangechi Mutu, Mask, from The Ark Collection, 2006, mixed media, 6-1/2 x 9-1/2 inches.

The images are indirectly explicit: women are touching themselves or one another, their ‘private’ parts masked or replaced with images of smiling women.

In Mask (figure 5) a pornographic image is layered onto an archival image of an African or Oceanic mask. The interior of the woman is cut below the eyes and her entire torso is hollowed out, revealing the mask as the core of this woman’s body. The nose of the mask cuts across her chest, creating an abstracted and angular illusion to her breast. The lips of the mask smiles coyly, where her pubic bone would be. These bodily shapes are ubiquitous in cubist collages. Her hair is cut out as well, whether they are thick braids, locks, or a more ‘mainstream’ style is left up to the interpretation of the viewer.

In, Michel Leiris’ Man and his Interior there is a story about a woman who happens upon an ox hanging in a butcher’s shop. Its belly is cut through, and she is so disgusted by the animal and at the idea that people contain intestinal viscera she resolves to never eat again. Subsequently the woman starves herself to death. Leiris uses this story to reflect on what purism can repress.

This allegory seems related in some way to Mutu’s Ark Collection, women who’s own intestinal viscera is ethnographic material. There is a conjoining of two different codes here, pornographic and ethnographic, and Mutu makes the correlations between the two clear by putting them in the same body. They function within one another and could not survive without.

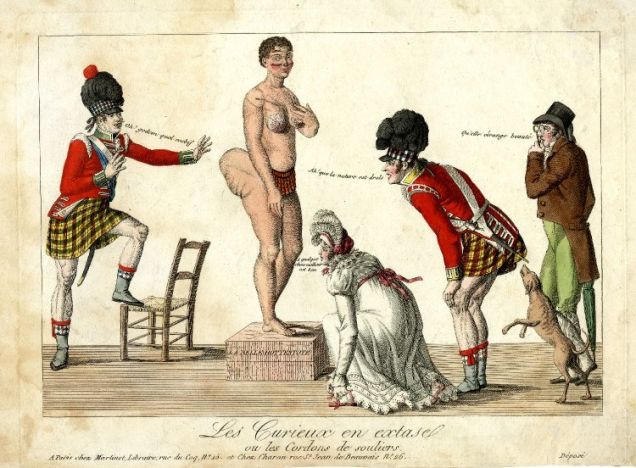

6. Saartije Baartman was sold around 1820’s.

In around the 1820’s, Saartjie Baartman was sold from the Gamtoos Valley of South Africa to London by an enterprising Scottish doctor. She spent years in France and Britain being exhibited for her anatomy, predominately for her butt and breasts (figure 6). After her death, Cuvier dissected her body, and displayed her remains, and for more than a century and a half, visitors could view her brain, skeleton and genitalia until she was buried. The treatment of Saartjie Baartman was an ethnographic excuse for human degradation. It is a history that informs Mutu’s work and illustrates how the ethnographic can be entitled in pornographic ways.

The women of the Ark Collection are more disjointed than Mutu’s previous women, and share aesthetic similarities with Histology of Uterine Tumors. While in Pin-ups and Classic Profiles Mutu is distinctly making hybrid figures, the figures in Ark Collection are more abstracted and as a result are a less subtle critique of how the female body is enhanced or contorted for historical and cultural purposes.

In 2014, Mutu presented the exhibition Nguva na Nyoka, meaning sirens and serpents in Kiswahili, which combines collage, video and sculptural works. The nguva, or dugong, is a large manatee-like mammal. It has a hippo-like head and fish-like tail. There are also allegories created around the nguva, constructed from Kenyan folklore, where it functions as a sort of sea nymph.

7. The screamer island dreamer, 2014. Courtesy the Artist and Victoria Miro, London.

In Mutu’s previous works she parses fiction from reality, but here there seems to be a mythology already in tact. Mutu acts more as observer and illustrator and less as collaborator. Not that this is any less invaluable. In her new work Mutu creates collages based off the nguva stories, (figure 7) The Screamer Island Dreamer, is less distinctly woman and more animal and monster like. It still has fashion model lips, but that is the lone, explicitly human feature. There is a serpent-like leech either clinging on or embedded into its belly, a possible reference to pregnancy or the maternal. Her images are hallucinations of the female body, incorporated with the animal or impossible anatomies; she shows internal organs writhing. They are dangerous and uncooperative, and she contrasts the intense and occasionally evil power of the Nguva to the purist mermaid of popular European culture.

9. From Nguva presentation, 2014.

There is one large sculptural piece within the Nguva series, which takes the form of an anaconda-type body the length of the room lies sleeping or dead on an elevated catwalk. Its middle section bulges with pregnancy or possibly food. I am reminded of her video with Santigold, The End of Eating Everything.

During the exhibition a video, titled Nguva, was screened. Mutu has worked in video off and on, but typically it does not get the same attention as her photomontages. The film opens with a Super 8 shot of the ocean, overlaid with the handwritten title Nguva (figure 9). It quickly jumps to darkness, where a woman and serpent like figures can be made out, accompanied by the high pitch of a whistle or electrical feedback. Her video feels harder to dissect than her collage works, because it seems less rooted in specific allegory. Instead there is an overall feeling of mythological and magical metamorphosis, all of her characters feel dangerous and powerful.

From Nguva presentation, 2014.

Mutu creates a surreal landscape between life and death, reality and dreams, the female body in the midst of transformation. She does not work within the confines of catharsis, to pick them a part seems apart of the process. The relationship between artist and the viewer is a dynamic one because while Mutu pieces together, recontextualizes and reclaims, we as viewers make our own associations and do our best to redefine what their origins mean to us. The final thing Mutu seems to be exploring is the relationship between herself, her characters and her viewers, and the relationship between pulling together and picking apart. This grants her viewers agency, and gives them the opportunity to interpret her proposal for reclamation. This in itself is reflective of the ideas she has imbued in her fictional characters— that everyone involved is granted an active role. She depicts Goddesses, monsters, and animals that incorporate a new and subversive mythology. She facilitates a transgression and in turn makes the viewer an accomplice in decoding imagery. If the female body does carry the language and nuances of culture, there is something conspiratorial in taking imagery— subverting it—and creating a new language.

1 Ades, Dawn, Simon Baker, and Fiona Bradley. “Deviations of Nature: Georges Bataille,” Undercover Surrealism: Georges Bataille and Documents. London: Hayward Gallery, 2006.

2 Frith, Susan. “Searching for Sara Baartman.” John Hopkins, Jh.edu.

3 Mutu, Wangechi. “Wangechi Mutu by Deborah Willis.” Interview by Deb Willis. Bombmagazine.org.

4 Mutu, Wangechi. “Wangechi Mutu’s Mystical Sirens & Serpents In London.” Okayafrica.com.