After all colonization was essentially based on the art of seeing – of seeing the other through the perspective or gaze of the western world. Or fixing the observed other in a frame or lens like photographer or a hunter tracing a wild thing through the pistol’s lens.

Athi Mongezeleli looks back on two controversial exhibitions of Alfreda Jaar in Johannesburg.

Frantz Fanon Tribute, 2016 (photo David Mann).

Alfredo Jaar’s Show

“I am haunted by the vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain…of starving or wounded children…” Kevin Carter’s suicide note. (1)

Alfredo Jaar’s Johannesburg shows at the Goodman Gallery and Wits Art Museum (WAM) respectively, came at an opportune moment. The pervasive aura of decolonization, from students to workers, seeks in the first instance to change the ways of “seeing” and “being” in the world. Colonization does not only refer to mere seizure of space through conquest. In its essence it exceeds the geographic reference to space (res nullius), to dispossession of mental, labor and ontological faculties. It is an overall stripping of the very essence by reducing the colonized into a palatable, consumable and disposable instrument. Decolonization can then only refer to retrieval of the pocketed and disfigured human essence by way of a radical overhauling of the colonial status quo.

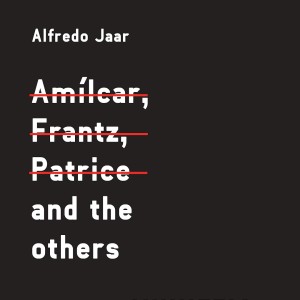

Goodman Gallery and WAM, offered two shows running concurrently, significantly titled Amilca, Frantz, Patrice and Others (1) and The Sounds of Silence (2)at respectively. Seen individually or together, both shows resonate with the current hypertensions in South Africa. They speak to the climate and echo its pervading sentiments.

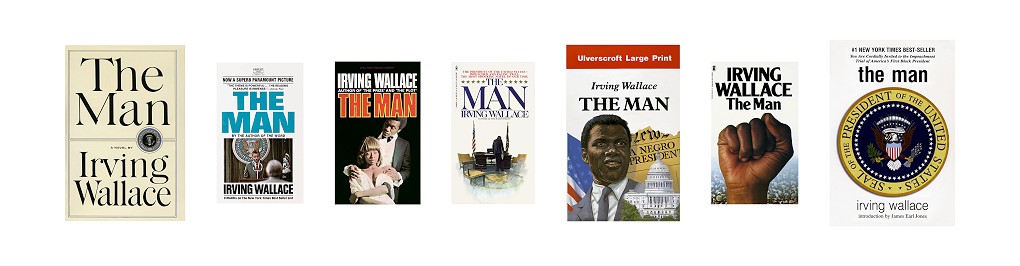

The Man, 2016.

The Man, 2016.

Due to this mood, the show by the Chilean born New Yorker is impossible to see outside this pervading lens. After all the idea of seeing, imaging and picturing is central to Jaar’s body of work. To “see” isn’t mere an automatically coded reflex, but always part of the larger project of social conditioning and interpellation. There’s always an aesthetic and ethic to seeing informed by particular libidinal interests. Seeing is contingent and constructed. But seeing is also, sometimes, unstable and in flux.

After all colonization was essentially based on the art of seeing – of seeing the other through the perspective or gaze of the western world. Or fixing the observed other in a frame or lens like photographer or a hunter tracing a wild thing through the pistol’s lens. Such a gaze is riddled with all the epistemological strictures, beginning in the early European Renaissance, which distinguished humans from the rest. This “rest” in which Africa fades at its unfathomable end, constituted the alien world on which violence was unscrupulously decreed.

Jaar’s projects concentrates not only on this continued liquidation of essence through denial of being and normalized misrepresentations in the media especially. It shows an awareness of the casual circulation of images in the public domain – its sensational penchant for caricature, and the spectacular, always drawn to the morbid and necrophilia, furthering its own perverted classic interests. These have been insatiable desires of the west – always looking from without, with a seeming inculpable and unaffected yet “sympathetic” gaze, while in reality depending, parasitically, on the wild thing’s flesh to live.

Kevin Carter, Starving Child Vulture, 1993 (copyright estate Carter).

After twenty years since Kevin Carter’s image, The Sound of Silence returns to the now half-forgotten but part of the global paragon of historical images – the famous and award-winning picture of the crouching Sudanese child pursued by a vulture. As an architect and filmmaker, Jaar draws quite intensely from these respective fields to illuminate what was concealed through the veil of global white empathy. As an iconic image in the world’s visual portfolio on Africa, Jaar’s video piece strips Carter’s project into its barest minimum.

The Sound of Silence, 2006.

The Sound of Silence, installation view, 2009.

A big rectangular structure sits transversally in the middle of the museum floor, sheathed in a metal cover, with florescent lights with a luminosity that blinds us like a camera flash. At the entrance, sits the museums marshal instructing the audience when and when not to go in. He sees me gushing into the museum with urgency, and rushes towards. Instructions are laid bare, “wait until it shows green. Now its red.” There’s a cross-like emblem at the entrance – red (no entry) cuts across horizontally and green (entry) rushes up vertically. It gleams green and I walk into the nocturnal space. There’s absolute silence, it screams. Kevin Carter’s name blinks and story unfolds, written across the screen. But in no time the story of a heroic South African photographer, the star of the famous anti-apartheid Bang-Bang Club, evolves to nightmare. At eve of the end of state apartheid, as the tale unfolds we realize that Carter hadn’t taken to kind the looming end of his perilous pastime of taking pictures while ducking bullets, and so he decided on another adventure of once again snapping decrepit blacks up North-east Africa. And yes, luckily, while strolling looking for the killer image, he stumbles into a little black child crippled to her knees by famine. A vulture was on site. He waited for its ambush. But alas, the vulture wasn’t too keen on feasting on black flesh in the presence of humans. Though it didn’t, the presence of the vulture in the scene was enough to keep us cringing at the prospects of the slowly dying child in the zoo that is Africa.

This was the image that won Carter the prestigious awards, but also pushed him to his suicide. Jaar pictures back to us a story of a white man’s picture that traded on the global currency of black social death. But still Carter’s suicide does not make this abruptly truncated life a bad end, but instead it is redemptive. Jaar tells us though the photographer died; the picture lived. So ironically Carter, by way of his participation in this economy of images, dies a hero. Contrary to our unspoken belief that his suicide was to himself and others, an index of self-sacrifice, an admission of culpability, punishing himself as a result of an encounter with the returned gaze of black graves. It is precisely through this premature death, that his infinitude was realized; living vicariously through his photograph. In fact his death confirms that Carter does not relinquish his insatiable appetite for preying on black bodies. He owns them even in death. Through his “symbolic wages of whiteness”, he ruptures the tombs of stammering graves, and waltzes back to the realm of living legends by memory.

Amilca, Frantz, Patrice and Others, installation view, 2016.

2016.

Fela Kuti Tribute, 2016 (photo David Mann).

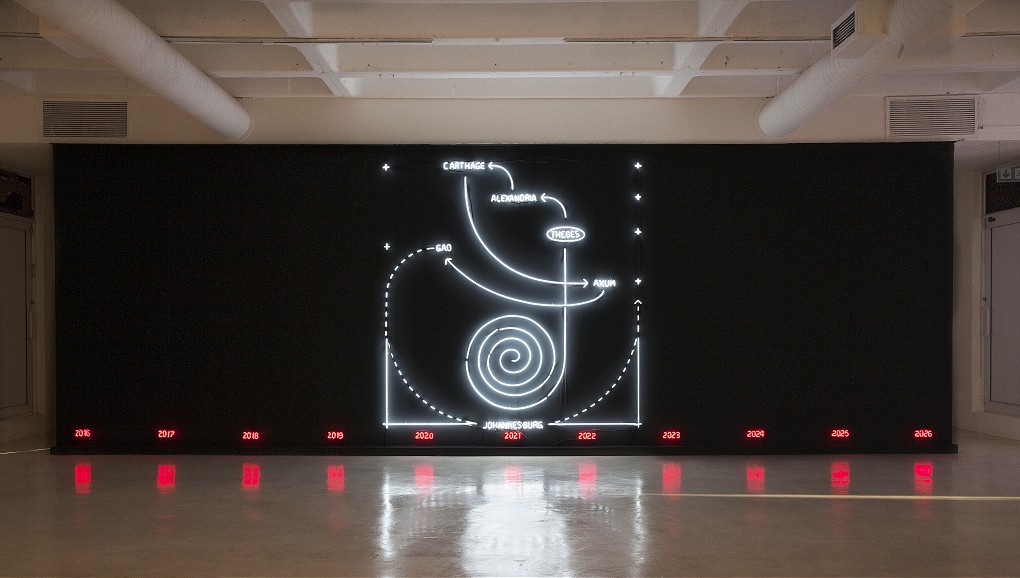

However in his Amilca, Frantz, Patrice and Others, Jaar takes a slightly positive stance or way of looking at Africa. From his futuristic cartographic wall installment titled Johannesburg 2026 (3), which shows “the elusive metropolis” (Mbembe and Nuttall) as a prominent trade centre to come, to his colorful appraisal of the four distinct figures of African anti-colonial struggles – Frantz fanon, Amilca Cabral, Patrice Lumumba and Fela Kuti – we’re presumably led to think of a different Africa. However his soundless video tribute to late former president Nelson Mandela has a bewitching aura of a subliminal critique. The picture of a slightly steaming teacup on piles of cheap jail blankets, recalls how capitalism turns everything into a consumer product, including the repackaging Mandela as Africa’s version of Santa Clause. There are also a number of other appraisals, reflections and reimaging of prominent figures and their works like Nina Simone’s revolutionary song, Mississippi Goddamn and Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

Despite his critical take on images, especially in the mass media’s production line, Jaar counters images with other images. From his, we see a different Africa. However, we must ask something about the status of this different difference? Does such seeing suggest a break from the strictures and structure of the world as we know it? Or does this positive rendering obliquely consents us to or immure us from the actual reality?

There’s just something about the stubbornness of the anti-black structure of the world that troubles this hyperactive attempt to re-render images about Africa. I think Fanon was thinking about this when he said, the black man has “no ontological resistance in the eyes of a white man.” In sense both Carter and Jaar seem to inconveniently meet in the fog, fighting over the black body, while it plods helplessly in between. Carter on one side searches for the spectacular carcass, while Jaar attempts to recuperate the corpse. This availability of the black body, irrespective of the artist’s intended interests, needs its own critical consideration. These are questions and concerns currently taking all sorts of shapes in current student and workers movements in South Africa and Jaar’s show could not be timelier.

1. When this photograph capturing the suffering of the Sudanese famine was published in the New York Times on March 26, 1993, the reader reaction was intense and not all positive. Some people said that Kevin Carter, the photojournalist who took this photo, was inhumane, that he should have dropped his camera to run to the little girl’s aid. The controversy only grew when, a few months later, he won the Pulitzer Prize for the photo. By the end of July, 1994, he was dead.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja is an art critic based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He is studying towards his MFA at Wits University.