KG_01.tif

Good Hope is a feeble attempt by the Rijksmuseum to bring better understanding to the ‘relationship’ between South Africa and the Netherlands. While there is merit in bringing awareness to this narrative, what it fails to do is bring home the message of how the colonized continue to struggle to break free from the shackles of oppression and it excels at continuing to pacify the voices of these people, allowing the Dutch audience to continue living in oblivion or perhaps ignorance.

South African art critics Alfred T.M Rossouw and Phumzile N. Twala on the exhibition Good Hope in Rijksmuseum Amsterdam.

Nelson Mandela, Leidseplein Amsterdam, 1990.

Good Hope: A Hopeless Exhibition in Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The persistence of Europe, through its colonial institutions, in telling a one-sided account of global history, sweeping under the rug all of the violence they’ve foisted on others in their pursuit of power, has created a cobweb of lies so thick that even they find it hard to get out of. Their continued muffling out of ‘other’ voices in the telling of global history, hiding behind having “consulted with specialists” and having their work anchored on scientific or concrete facts, has gotten them so deep in their lies that they fail to see the consequences of their violent past actions on the present lives of so many people.

One such act of European arrogance, perpetuated through one of their biggest colonial institutions, is the Good Hope exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

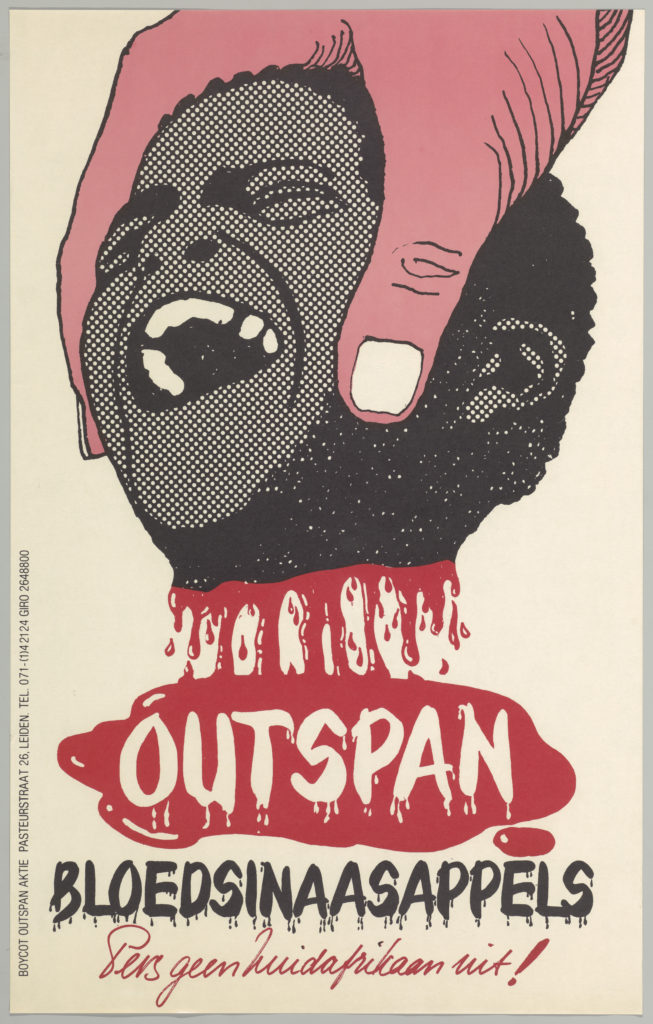

Rob van der Aa, Outspan bloedsinaasappels, Pers geen Zuidafrikaan uit, 1975. International Institue for Social History, Amsterdam.

The imposing figure of Jan van Riebeeck looms large and ever-present in the Good Hope exhibition. Some of the South Africans who were present for a recent walkabout during the opening day of the exhibition, led by the curator Martine Gosselink, are unfortunately products of a schooling system that emphasised the presence of this figure in their history books for many years. As scholars in South Africa, Jan van Riebeeck has always been a point of departure in their understanding of the historical ‘relationship’ between South Africa and the Netherlands. And here he was again, a symbol positioned as the starting point to an exhibition which, according to the curator, seeks to give the museum’s Dutch audience a better understanding of the historical relationship between the two countries.

Installation View, Photo Olivier Middendorp.

Honesty speaking, the two grand portraits of Jan van Riebeeck and his wife Maria de la Quellerie, which act as a welcoming mat for visitors who came to the exhibition, represent a physical manifestation of a severe case of European selective amnesia – i.e. their sick ability to remember and retell only certain parts of its violent history – more than anything else.

Charles Bell, Jan van Riebeeck landed at the Cape.

The danger of putting such an exhibition together is that, in their effort to appeal to their ‘target’ audience, curators can leave other narratives twisted, make them insignificant, or completely ignore them. While Gosselink and her colleagues have curated a monumental exhibition, the narrative it portrays is found painfully wanting. The exhibition, which is meant to explore ‘what took place between 1652, when van Riebeeck landed at the Cape and Mandela’s visit to Amsterdam in 1990’, feels more like a nostalgic retelling of a past of conquest – sans the violence foisted on and the dehumanization of a lot of people that came with it.

Marlene Dumas, from the series Being Held by Others, 1989.

After admitting that this is where their introspection will begin, the exhibition, together with the catalogue that accompanies it, begins the ‘scrutiny’ of this ‘shared history of The Netherlands and South Africa’ in the days leading up to van Riebeeck’s docking on the Southern-most tip of Africa. Then, after again admitting that they weren’t able to find other accounts of this history besides the ones from the colonialists, the narrative perpetuated throughout the exhibition continues with an erasure of the agency and abuse of the Natives that were found in South Africa by the colonialists by failing to show evidence of any resistance against them and paints them as the agitators of the violence that transpired throughout the early years of the Dutch colonization project.

The main language used in the exhibition, Dutch, is translated for English-speakers but fails to evoke the magnitude of the atrocities committed by the VOC and Dutch settlers since van Riebeeck’s arrival at the Cape. The language used romanticises a rather violent history and almost nullifies the brutality and violence suffered by the Khoi at the Cape at the hands of Dutch settlers. The imagery used in the exhibition also poeticizes the realities of colonial conquest.

The use of words such as “intermenging” alludes towards voluntary “interbreeding,” although this wasn’t always the case. The word “rape” is sorely missing in both the exhibition and its accompanying catalogue.

Installation View, Photo Olivier Middendorp.

The decision to depict the historical relationship between these two countries, and the ‘reciprocal influences between them,’ and still insist on having curatorial autonomy shows how uninterested the curators of the exhibition, and Europe as a whole, are in including ‘other’ voices in the narration of global history. The fact that the curators believe that the 10 trips they’ve made to South Africa over a three year period, and the interactions they had with the three hundred ‘specialists’, is enough to give them authority on how to narrate the story of the Khoi, is proof of how arrogant Europe and its institutions can be.

.

The catalogue, edited by Gosselink, Maria Holtrop and Robert Ross, is another example of lack of attention to detail or blatant ignorance. Surely one of the “three hundred South Africans consulted” throughout the three-year process could have pointed out the incorrect spelling of the name of Mbuyisa Makhubu, not once, but twice? Where was the prudence?

.

The narrative of this exhibition, told from a Western point of view, enforces the sentiment that allows white privilege to distort and justify the persecution of black bodies.

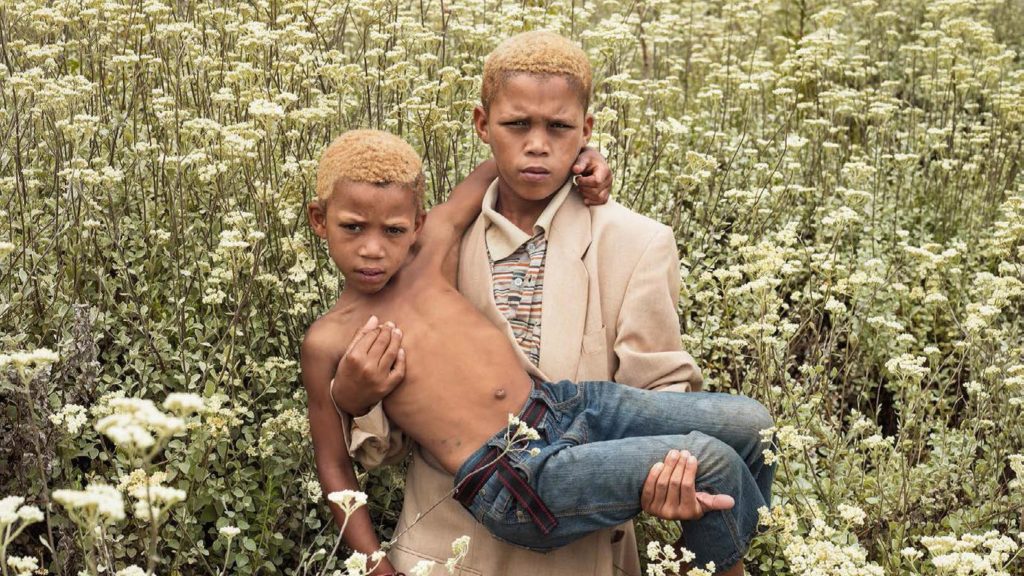

Pieter Hugo, from Series 1994, 2016.

A lack of imagination on the part of the curator (or the board of the Rijksmuseum as we were told) made it possible for yet another white body to tell (and profit from) the story of black bodies. The “born-free” generation narrative portrayed through photography by Pieter Hugo was in no way reflective of the present-day realities faced by this generation. Why not embody the spirit of “good hope” by giving the platform to a young, talented and dynamic black photographer instead?

.

Good Hope is a feeble attempt by the Rijksmuseum to bring better understanding to the ‘relationship’ between South Africa and the Netherlands. While there is merit in bringing awareness to this narrative, what it fails to do is bring home the message of how the colonized continue to struggle to break free from the shackles of oppression and it excels at continuing to pacify the voices of these people, allowing the Dutch audience to continue living in oblivion or perhaps ignorance.

.

As long as Dutch historians and curators continue on this path, there is no good hope; the situation is rather hopeless.