It would be a shame if the festival is discontinued before it has reached its potential, and before we can see the impact it can make. As for plein-air paintings, even the harshest of critics can succumb to that one nostalgic picture. Plein-air paintings call attention for the places they depict. They encourage a dialogue about the things that happen there. In an ideal world, the Lamu Painters Festival would work to create awareness about Lamu and to promote the preservation of a special place.

Zihan Kassam on The Lamu Art festivals in Kenya

The Lamu Art Festivals in Kenya

A Change Is Gonna Come

It used to be predictable, but the plein-air painting festival in Lamu is changing shape. The Lamu Painters Festival is a biennale that was founded in 2011 and is directed by Herbert Menzer, who is a philanthropist and holiday-home owner. Menzer invites artists, most of them European, to work in the open air and paint attractive scenes of the island. Resident admirers pass by, greet the artists, watch them paint, and attend the exhibitions. But where does plein-air painting stand in a world consumed by conceptual art?

.

Outdoor painting became popular in the 1840’s with the introduction of paints in a tube, which allowed an artist to carry paints to an observation point to reproduce the scene before them. The tradition began with the Barbizon School of oil painters in France. Today plein-air painting still occurs, but is it outdated? One cannot deny that plein-air painting is an effective way to develop technical drawing and painting skills, and there are certainly alluring plein-air paintings that ease the eye and soften the heart. Then perhaps the better questions are: Do plein-air paintings serve a purpose? and Does art need to have an objective?

.

This year’s Lamu Painters Festival (February 2 – 19) was fused with the second edition of the annual Lamu Art Festival (February 17 -19), which is also organized by Menzer and partners. The Lamu Art Festival includes a group exhibition at the Lamu Fort, a dhow race, a musical component with live concerts, a sunset sail, and dj parties organized by Rachael Feilier of Diamond Beach Hotel. Typically, each of the festivals host between15 to 20 visual artists, and the majority of the artists are German, Dutch and Russian. The merging of the two festivals this year doubled the number of participating artists. Organizing 41 artists is no easy feat, even with a larger administration team. Menzer should be acknowledged and praised for his open-handedness and perseverance for implementing two momentous affairs. The work of making Lamu an ‘Island of Festivals’ is a demanding task, to say the least.

.

It requires remarkable coordination to bring copious numbers of artists together. Menzer and his team ensured that each of the participating artists had a space to show their work despite the new format of the combined festivals. By February 15, paintings by the quintessential plein-air painters were hung at the Baitil Aman Hotel, which is the standard exhibition space for the Lamu Painters Festival. Then the conceptual artists, installation artists, Kenyan artists, and experimental plein-air painters were shown together in a large exhibition at the Lamu Fort for the Lamu Art Festival. The inclusion of new blood, new ideas and a variety of contemporary art on display has the ability to surge the number of people who attend art festivals, which sometimes can be limited to a small contingent of followers.

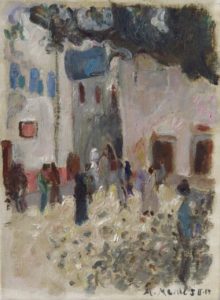

Marjolein Menke, Corner of Luma Square, 2017

The reason for the original scepticism is because it is genuinely difficult to understand the value of plein-air painting. How are the artists satisfied by bootlegging what nature or man has already fashioned once? And how can a buyer be satisfied with something that looks just like a photograph in paint? What about creativity? What about artistic concept? It is much easier to appreciate plein-air painting when the artist is not creating a replica, but instead, an interpretation, of what they see. Dutch artist Marjolein Menke from the Lamu Painters Festival explains. “In plein air painting, you are surrounded by the subject. There is just the subject to breathe.” Of portraiture in particular, she says, “Working in the direct presence of the subject is seductive and so easily creates a deep concentration.” Menke makes many good points. “Only the painter knows, the moment he starts painting. He has to know, in whatever his way of knowing might be. Starting to paint without being struck by what to him is the essence, makes no sense. Painting is not about picture. It is about meaning; it is the difference between image and story.”

.

While Menke shares her insight in to the plein-air technique, there are still no answers about the lacklustre palette shared many of the plein-air artists. The palette is typically comprised of dull browns, greys and other muted shades, which tend to make the paintings feel the same. Lamu is alive with colour and it is unsettling to see scenes reproduced in a flat palette. What is also baffling is the unremitting focus on seascapes. Lamu offers so much more than ocean views. There are the intricacies of the Swahili Muslim culture and engrossing Kenyan idiosyncrasies. But aside from this, there were some competent artists with compelling paintings. Russian painter Natalia Dik seduced the crowd with her pentaptych Africa-4 Elements in Colours. In cool tones and feathery strokes, she captured the spirit of the people, the animals and the place. With Natalia Dik work, you can feel her connection to her subject matter.

Diedrick Vermeulen, Luma Square (photo: Roland Klemp)

Diedrick Vermeulen captured a scene attempted by so many of the painters who visit Lamu. His painting Lamu Square is an exuberant impression of the steps that lead up to the Lamu Fort. Made of squiggles and abrupt lashes of oil paint, Vermeulen uses touches of red and yellow to pull you in to the picture. Once you are in, you see a crowd standing under the big tree in the courtyard. It is an energetic painting that can be enjoyed by plein-air and abstract enthusiasts alike. Vermeulen, who lives between Holland and Portugal, is no stranger to the Lamu Painters Festival but he keeps to himself, uses his words sparingly and saves his energy and wisdom for the paintbrush. Rob Jacobs’ approaches plein-air with a kind of friskiness. He creates colourful, dynamic contemporary expressions of Lamu beach-life. Jacobs strikes a nice balance between technical expertise, inspiration and recreation.

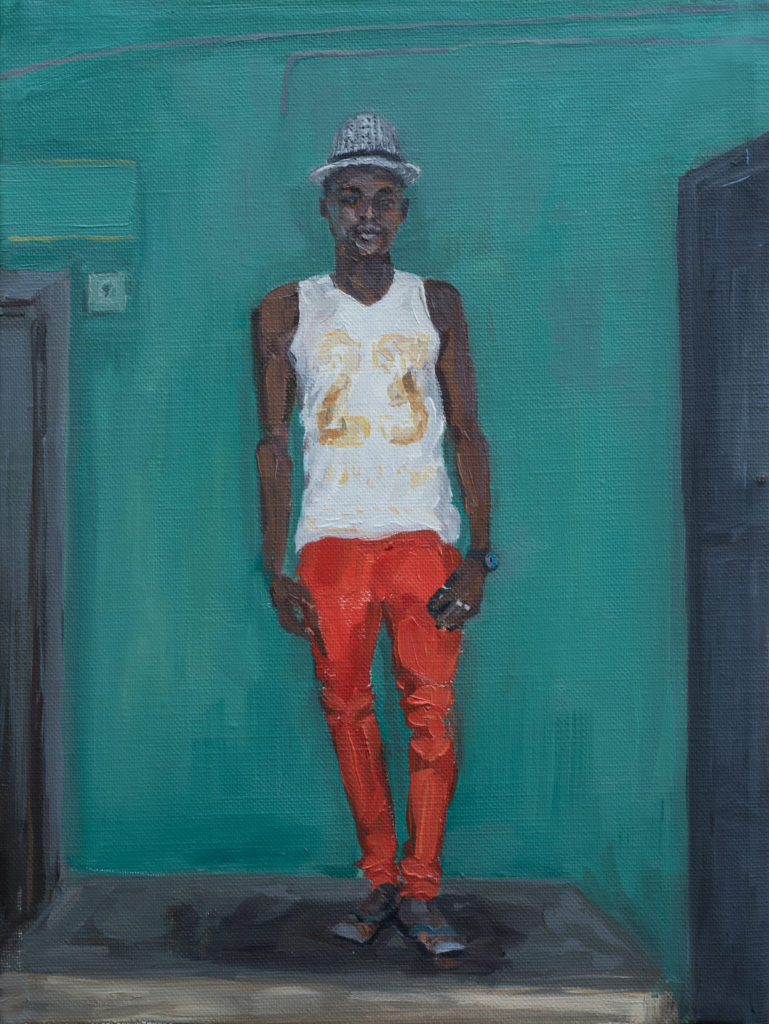

Hartmut Beier, 23, 2017

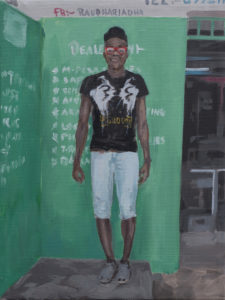

It was inspiring to see a few plein-air artists use the Lamu experience to explore the island a little more. This is easier for artists who are already acquainted with the place. Hartmut Beier (Hardy) from Hamburg, Germany, decided to spend his second trip to Lamu frequenting Gardeni, which lies on the outskirts of Lamu Town. He spent six weeks painting portraits of the people there. Gardeni is considerably poorer than the interior of Lamu, and Hardy worked to capture the feeling of the place. His portraits captured the poverty of the people but also their sense of fashion and sense of humour. Two of his portraits stood out. One called Safari, featuring a young man leaning against an Mpesa kiosk painted in magnetic green. The other, the same size (30x40cm), called 23, features a hipster leaning against an attractive aqua-blue wall of a shop. The paintings complement each. They belong together.

Hartmut Beier, Safari, 2017.

Also from Hamburg, Germany were the dynamic duo Marc Einsiedel and Felix Jung, travelling artists who have worked together for the last seven years under the Wearevisual umbrella. They conduct material studies using found objects and locally sourced materials specific to each place they visit. Producing a variety of installations, they inspire youth, showing them that art is not limited to drawing or painting; it is about investigating concepts and using those concepts to change the way we think and live. Einsiedel and Jung produced a wealth of artwork during their six weeks in Lamu including a whale bone sculpture on Shela beach and a make-shift kaleidoscope for all to try out. A giant flag hung in the atrium of Lamu Fort. Made from textiles found in Lamu, each unique material found or bought, represented a different walk of life in Lamu.

Juliana Bastos Oliviera, Sound Installation, 2017 (photo: Eric Gitonga)

Originally from Portugal but living in Hamburg, theatre and performance artist Juliana Bastos Oliviera produced a sound installation; a compilation of sounds from Lamu Island. This was a new concept for many Lamu locals who attended the exhibition. The sound emanated from an installation of burnt tin cans that hung on the fort wall. It was hard to tell where the familiars sound came from and so the cat meowing or the man snoring took many visitors by surprise. Other compelling artwork included Eveline van de Griends’s coral stone sculptures made with the disappearing Vidaka technique and Ajax Axe’s mixed-media installation , a pyramid of plastic bottles that calls in to question our priorities and what the future holds for humanity and the planet.

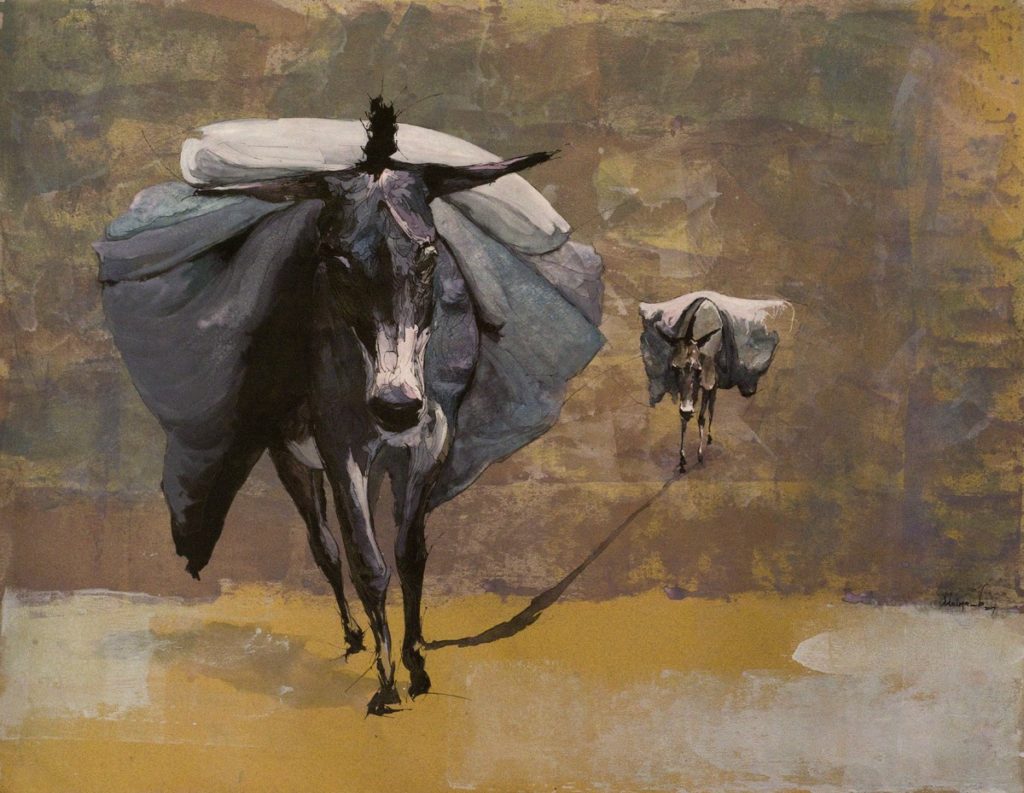

Maina Boniface, Lamu Land Transport, 2017 (photo: Eric Gitonga)

For several weeks before the festival the island was dotted with many European artists and a handful of African artists. Usually the Kenyan representation at the Lamu Painter’s Festival is almost invisible but this year, with just a few more artists on board the change was both palpable and positive. The Nairobi-based artists altered the flavour of the two exhibitions, refreshing the audience with their atypical approaches to plein air. A small ink work by Maina Boniface called Lamu Land Transport (42cm x60cm) turned heads and became the topic of conversation at many events. It is a surreal depiction of two donkeys, one following the other in to a nowhere-land of coral tones and texture. The expressions of the sweet spirits induce a sense of woefulness. The shadow of the leading donkey falls in a Dali-esque streak on to the distant donkey. It becomes the cord that ties the fate of two sombre, broken-hearted souls.

Peter Ngugi, from Walls Have Ears Series, 2017 (photo Roland Klemp).

Lamu is a live colour-field, and when contemporary artists like Maina Boniface pull from its vibrant palette, to produce rare interpretations of the place, magic happens. Peter Ngugi’s Lamu palette has an equally captivating effect. He pulled from the warm russet tones, ochre and ginger, contrasting them with castes of blue and green. He extracted patterns from traditional Swahili architecture and he took notice of the designs from Swahili traditional attire. Combining these Lamu effects, Ngugi produced nine figurative paintings each showing one, two or three Lamu residents going about their day. He stencilled circular Swahili motifs, over and under the Lamu men and women, producing a fancy veneer effect in his paintings. In select pieces, a megaphone is featured, which in Lamu, is used for the call to prayer. Ngugi explores how the megaphone is used in Kenya, comparing its use in Lamu with other parts of the country, mainly Central Kenya, where it is used for political campaigns. By studying the role of the megaphone in different places, Ngugi is creating an awareness of the religious, political and social philosophies and propaganda circulated in Kenya.

Peter Ngugi, painting live in Shela, 2017 (photo: Roland Klemp)

“This series is an investigation into the dissemination of information,” Ngugi says, in his own words, about the larger Monologue Series he is working on. “It is a general look at how information is passed from source down to the intended recipient. I look at how this information is shared among the recipients and how it affects the actions and decisions they make.” Ngugi’s paintings at Lamu Fort were small, 42cm x 30cm each and he hung them in three rows and three columns directly on the fort wall. He called this mini-series of his, which falls under his larger Monologue Series, Walls Have Ears. Walls Have Ears was immediately snapped up by an unnamed collector rumoured to live in an old fort in nearby Shela.

Peter Ngugi, Under the Kahawa Tree, 2016.

At the end of 2016, Peter Ngugi’s impressive 32 foot installation Under the Kahawa Tree was commissioned at the Hub, a new outdoor mall in Nairobi. Made from stainless steel spoons and aluminium sheet metal, he fashioned a giant coffee tree and under it, the different people who have benefitted from an education through small scale coffee farming in Kenya. There is a pervasive mall culture in Nairobi. Two Rivers is another opulent mall with a 65,000 square metre shopping facility. It just opened, in February 2017, and the gateways flaunt four mosaic murals, two hundred metres each, one of which depicts a shopaholic revelling in her loot. They are by Kenyan artist Maryann Muthoni. It seems there is a new trend in which international organizations in Kenya are commissioning local artists to create public art. All this to say that Kenyan contemporary artists are generating superior artwork and the interest from the local and global audience continues to grow. This was evident in Lamu where the artwork by Kenyan artists at the Lamu Fort received a lot of attention comparatively.

Nadia Wanjiru, painting live in Shela

This kind of interest is heartening for emergent Kenyan artists like Waweru Gichuhi and Nduta Kariuki who are stepping in to the art market in Kenya and slowly building a name for themselves. Both artists concentrated on portraits during the Lamu Painters Festival. There was also Nadia Wanjiru Wamunyu whose artwork has evolved significantly since the last time she participated in the festival (2015) and she continues to impress the crowd with her drawings and paintings, last year of baobabs and this year of the Lamu donkeys. Then there is James Njoroge, a respected, more established artist from Nairobi whose impressive collages of Lamu brought life to his segment of the Lamu Fort. He is a master colourist. The Kenyan artists did not feel the need to conform to the quintessential plein-air oil paintings. They worked in mixed-media with progressive interpretations of life in modern-day Lamu.

.

Also from the contingent of artists residing in Kenya, was British artist Dale Webster, a talented portrait artist who used his first experience in Lamu to juxtapose the psychological interiors of his subjects with the physical exteriors of Lamu. Webster was grossly aware of the contradictions of life in Shela and the fact that many holiday-makers ignore the hardship on the island. Incorporating elements from their surroundings, his paintings captured some of the sting and soreness felt by his sitters. Or perhaps he was capturing his emotions in their faces? Three of his portraits were exhibited at the Lamu Fort for the Lamu Art Festival.

Fitsum Berhe Woldelibanos, Untitled, 2017 (photo: Eric Gitonga)

Also showing at Lamu Fort was popular Eritrean artist Fitsum Berhe Woldelibanos, who has been living in Nairobi since 2003. With six colourful acrylic paintings, he introduced a fresh concept. He has taken his brand of portraits to a new place. In his latest series Lamu Studio 70’s, inspired by old photographs from Lamu, he is exploring the construction of identity and memory though picture-taking. Fitsum looks at the various roles that photographs have played in the past and present. What do people want to be in front of the camera? Painted on the rooftop terrace of Fishbone house in Shela, Woldelibanos depicted people of Lamu-past – families, couples, a bride with flowers – in starched poses and prescribed settings. They are all creating a legacy through photographs. Having returned to Nairobi, the series continues to evolve but it will be difficult to outshine his untitled beauty; an arresting painting, in red and blue, featuring a Swahili man sitting on the sofa in his family room in Lamu.

.

From Karen in Nairobi is British watercolour maestro Sophie Walbeoffe. Amazingly, she paints with both hands and can produce a painting within minutes. Her technical competency resounds in her sound compositions. Walbeoffe continues to paint pretty pictures that tackle only the surface of Lamu existence; Dhow sails in fairy pink, wispy clouds in lollipop orange, rainbow-colour palms bopping in the wind, hints of dazzling purple and pink. Other regulars to the island are aware that there are two sides to the Lamu equation. There is the blue sea, sunshine, handsome houses and margaritas at Peponi Hotel but there is also the steep decline in tourism, a new port that threatens local business, chronic land grabbing and an impending coal plant that threatens the environment. There is also a serious problem with narcotics and a shortage of concern for the welfare of the residents and the preservation of local culture.

.

To be fair, these are difficult things to capture through plein-air painting, definitely not as much fun, and probably not the point for many artists and art collectors. And perhaps it serves Lamu better to share beautiful images of a place that is definitely worth visiting? But then again, if we ignore certain aspects of Lamu life and if we do not use art for the sake of dialogue, who will know about what is happening to such a special place and who will help? Walbeoffe has a large following, mostly tourists and expatriates, who love Kenya and her fairytale depictions of it. The Karen audience especially, was excited about the launch of her latest book ‘An Artist’s Impression on Lamu’, produced by Herbert Menzer and written by Julia Seth Smith and Errol Trzebinski. The Lamu edition of the book launch, which preceded the Nairobi edition, took place at Lamu Fort where she temporarily showcased some of her watercolour fantasies.

.

The inclusion of conceptual art is transforming the Lamu Art Festival. If it is supported by local government, it stands to evolve even more. It would be a shame if the festival is discontinued before it has reached its potential, and before we can see the impact it can make. As for plein-air paintings, even the harshest of critics can succumb to that one nostalgic picture. Plein-air paintings call attention for the places they depict. They encourage a dialogue about the things that happen there. In an ideal world, the Lamu Painters Festival would work to create awareness about Lamu and to promote the preservation of a special place.