“Yet perhaps even more impactful than the biennale’s official exhibitions are the more than 250 unofficial OFF events, exhibitions and happenings that their occasion engenders, providing a more accurate look into the city’s ever-growing contemporary art scene. Independently organized and funded, the OFF led local art enthusiasts and visitors like me on a scavenger hunt across the city, aided by blue banners posted along the streets and a packet of no less than six maps detailing the locations of programs within Dakar and across other parts of Senegal, including Thiès, Lac Rose, Saint Louis and elsewhere.”

Perrin Lathrop is impressed by the OFF- program of Dak’Art.

OFF Site: Dak’art 2014

Soon after my arrival at the Village de la Biennale, the host of the International Exhibition for this year’s edition of Dak’art: the 11thBiennale of Contemporary African Art, I was greeted by an employee stationed at the site. Led by this slightly overeager gentleman through the former television studio’s sprawling buildings on the busy Route de Rufisque, my attention was directed to an arresting sculptural installation by Tunisian artist Faten Rouissi. My guide proudly proclaimed that this piece was the winner. Of which prize (Le Prix de la Ville de Dakar), I did not find out until following up with my own research later on.

Faten Rouissi, “Le fantôme de la liberté (Malla Ghassra),” 2012, Village de la Biennale.

Faten Rouissi, “Le fantôme de la liberté (Malla Ghassra),” 2012, Village de la Biennale.

Seat-less toilets were arranged like a gathering of figureheads around an oval conference table set upon a platform with microphones, pairs of eyeglasses and rolls of toilet paper strewn across it. Entitled “Le fantôme de la liberté (Malla Ghassra)” (2012), the entire tableau was doused in a particularly assaulting shade of yellow. Made soon after the 2011 so-called Jasmine Revolution in Tunisia, the piece demonstrates the artist’s frustration following the elections that the revolution wrought. Plainly moved by the work, my guide found the topical theme of ineffectual and corrupt political governance to resonate with his own experience in Senegal. As I moved on to look at other works, a second biennale employee arrived with a feather duster to clean off the installation. My guide took this opportunity to carefully adjust one of the pairs of glasses on the tabletop. A gesture that would perhaps be frowned upon elsewhere, I saw it as a sign of his personal investment in the work, taking its appearance and preservation into his own safekeeping.

The overarching theme for the International Exhibition, and this year’s biennale in general, was “Producing the common.” Inspired by the literary theorist Michael Hardt, curators Elise Atangana, Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi and Abdelkader Damani write in their joint curatorial statement that they “seek to connect politics and aesthetics in a vigorous and sustained way” with their exhibition choices.(1) My biennale guide’s actions during my visit to the Village quite clearly declare the success of their mission. Yet perhaps even more impactful than the biennale’s official exhibitions are the more than 250 unofficial OFF events, exhibitions and happenings that their occasion engenders, providing a more accurate look into the city’s ever-growing contemporary art scene. Independently organized and funded, the OFF led local art enthusiasts and visitors like me on a scavenger hunt across the city, aided by blue banners posted along the streets and a packet of no less than six maps detailing the locations of programs within Dakar and across other parts of Senegal, including Thiès, Lac Rose, Saint Louis and elsewhere. Haggling with cabdrivers or traipsing through dusty streets under the blazing mid-afternoon sun, I found myself searching for art in unlikely places, often puzzling locals who I encountered along the way to the restaurants, cafes, hospitals, hotels, government buildings, nightclubs, banks, gas stations, former factories and more traditional art galleries that promised to reward me for my diligence. At points I was disappointed, at others blown away. But this mix of the good and the bad is endemic to the ethos of the OFF—and part of the fun. In an interview with the journal Contemporary And, OFF initiator and coordinator Mauro Petroni confirms, “…we want to protect the spirit of freedom that goes together with improvisation and amateurism, but also with freshness and sympathy.” (2) Thus, all entries to OFF are accepted: the one stipulation is the presentation of a work of contemporary art.

Ousmane Sow, installation, Eiffage Sénégal

Ousmane Sow, installation, Eiffage Sénégal

Yet some of the venues I visited had curated museum quality monographic exhibitions. The visceral, larger than life figural sculptures of celebrated Senegalese artist Ousmane Sow filled the courtyard of the Eiffage Sénégal headquarters—one of the corporate underwriters of OFF. Evoking bondage and slavery, Sow’s moving, alienated figures are covered in flesh that seems to come directly from the earth. The artist often uses his work to make investigations into different cultures, here the Nuba, Peul and Masai ethnic groups. During my visit, clean pressed bankers skirted around these intrusive strangers while I somewhat uncomfortably examined the scars, blank expressions and bodily contortions that made them appear permanently wounded.

Soly Cissé, installation, Hôtel de Ville.

Soly Cissé, installation, Hôtel de Ville.

Further downtown, in the court of the Hôtel de Ville, a more fantastical assemblage of bronze sculptures welcomed me. For his exhibition, Senegalese artist Soly Cissé created a series of storybook characters come to life, presided over by a throned king and queen. Intricately rendered animals, including dinosaurs, snakes, birds, lizards and other more imaginative beasts were paired in conversational vignettes interspersed with hulking headless court ladies and knights atop their steeds. I wandered in and out of the sculptures, contemplating the imaginary royal past from which they had risen.

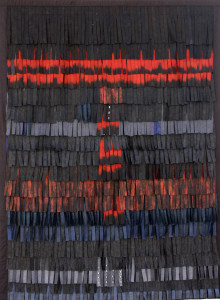

Abdoulaye Konaté, installation, Galerie le Manège.

Abdoulaye Konaté, installation, Galerie le Manège.

Down in the Plateau neighborhood, near the Corniche Est, the Institut Français’ Galerie le Manège hosted an exhibition of well-known Malian artist Abdoulaye Konaté’s wall hangings. In these works, Konaté plays with the formal qualities of the quilt to take up social questions such as the spread of AIDS, the global war against Islamic culture, biometrics and crossing borders with flattened figural compositions. In other, to me, more successful examples, he explores abstraction by sewing swatches of colored fabric in rows that create differently patterned variations depending on the direction of the breeze. The vast, whitewashed architecture of the gallery, with its high ceiling held up by colonnades of wooden pillars, made the hangings appear like tapestries in a grand cathedral.

Other sites presented group exhibitions that provided perspective on the local art scene or offered insight into artistic developments from further afield. The Musée Boribana, a contemporary art museum in the northern part of the city founded by Guyanese-American actress C.C.H. Pounder and her husband, Boubacar Koné, showcased the ceramics of Gene Pearson (Jamaica), the mannequin-like sculptures of Cheikh Diouf (Senegal) and the manuscripts of Abdoulaye Ndoye (Senegal). I found Ndoye’s floor to ceiling scrolls inscribed with elegant, invented script a thoughtful commentary on the fragility of written historical knowledge and narrative.

Abdoulaye Ndoye, Musée Boribana

Abdoulaye Ndoye, Musée Boribana

Nearby, the Senegalese branch of Fondation Total, situated behind an actual Total gas station, presented an informative exhibition on the important journal Présence Africaine and hosted a round table of scholars to discuss its legacy. The site also gave space to the Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire-based Galerie Cécile Fakhoury for an exhibition that featured a range of talented and diverse artists, including Fabrice Monteiro (Belgium/Senegal), Latifa Pouye (Senegal), Aboudia (Côte d’Ivoire), Nestor Da (Côte d’Ivoire), François-Xavier Gbré (France/Côte d’Ivoire), Vincent Michéa (France/Senegal), Cheikh Ndiaye (Senegal/France), Virginia Ryan (Australia/Italy/Côte d’Ivoire) and Paul Sika (Côte d’Ivoire).

Paul Sika, “Mister tout mignon” series, Fondation Total.

Paul Sika, “Mister tout mignon” series, Fondation Total.

Their work took up a range of mediums and techniques, including installation, paintings, photography and collage, but standouts were Paul Sika’s neon, over-saturated, collaged and carefully constructed photographic tableaus that draw on the fashion and advertising industry to comment upon African popular culture. On the opposite side of the Dakar airport from Fondation Total sits the Village des Arts, occupying the site of a former encampment for Chinese laborers commissioned to build the adjacent Stade Léopold Sédar Senghor in the 1980s. Now a thriving arts community, it hosted a group exhibition highlighting recent work by the many local artists and artisans who maintain studios there. I had the pleasure of speaking with artist Moussa Sakho, who riffs off traditional sous verre (glass) painting in his work.

Moussa Sakho’s Studio, Village des Arts.

Moussa Sakho’s Studio, Village des Arts.

Many exhibitions were more blatantly commercial in nature but introduced the work of some innovative and talented local artists. At the swanky Villa Racine, a hotel downtown, Cheikhou Bâ’s bright large-scale Basquiat-esque paintings with pictographic symbols and figurations, written messages, drips of paint and flat planes of color were popular with collectors.

At the close by Galerie Arte, I had to wade through rooms stuffed full with African fabrics, jewelry, sculpture, furniture and other decorative arts to find the paintings of two Beninese artists Dominique Zinkpe and Tchief. In a style similar to Cheikhou Bâ’s, Tchief’s works were almost archaeological investigations into abstraction, with markings and notations scratched into the paintings’ surfaces. The Atelier Fer et Verre presented beautiful abstract, watercolor-inspired works on glass in various organic shapes, some inset into slices of tree trunks, others cut into abstracted oblong bird’s wings.

Fally Sene Sow, in front of one of his ‘paintings’.

Fally Sene Sow, in front of one of his ‘paintings’.

At the Goethe-Institut Sénégal the twenty-five year old artist Fally Sene Sow had a breathtaking show of recent works that also play on the sous verre painting tradition with collages featuring street scenes inspired by Colobane, the Dakar neighborhood where he spent his youth. Sene Sow uses detritus from the urban environment like instant coffee wrappers and used tinfoil to draw viewers into his noisy, sometimes gloomy world with tantalizing glittering surfaces and intricate details.

Zanele Muholi, participating in Precarious Imaging, Raw Material Company.

Zanele Muholi, participating in Precarious Imaging, Raw Material Company.

Still other more powerful and thought-provoking exhibitions took up community engagement and social change as priorities. The internationally renowned contemporary art space Raw Material Company contributed a groundbreaking exhibition co-organized by Koyo Kouoh and Ato Malinda entitled Precarious Imaging: Visibility and Media Surrounding African Queerness that explored homosexuality in Africa with conceptual and documentary work by Kader Attia (Algeria/France), Zanele Muholi (South Africa), Andrew Esiebo (Nigeria), Jim Chuchu (Kenya) and Amanda Kerdahi M. (Egypt). Soon after opening the show, the gallery was vandalized for the previously hidden lifestyles it had brought to the surface and faced shutdown by the authorities. The Senegalese government, which prohibits homosexuality, also suspended all other Dak’art exhibitions dealing with the subject.(3)

Kër Thiossane, an art space and multimedia center that also aims to serve the interests of the local community used the biennale as an occasion to organize Afropixel 4, a festival of workshops focused on digital mapping, open source software and a host of other diverse programs. When I visited, a member of the community was making use of a computer built by workshop participants the previous week. Satellite studios down the street from the art space host artisans and media practitioners, counting a three-dimensional printer called the FabLab among their ranks. Nearby in the dilapidated SICAP housing project, Kër Thiossane also launched a green space revitalization project under the banner Jardins de Resistance. The project supports the development of a community garden and communal space where meals can be shared or concerts and other events held. These two projects come together with the inauguration of an alternative currency designed by artist Mansour Ciss that can be earned by working in the garden and used to buy goods from neighborhood artists or in the local grocery.

Despite the seemingly endless days I spent going from one OFF site to the next, I could never have visited them all. The decentralized, improvisatory, expansive yet hyper-localized nature of the OFF allows for an innovation and excitement that the official exhibitions never could, offering a glimpse into the neighborhoods and street corners where the real creative energy of the biennale takes effect. My insights just scratch the surface of an art world that would take years, not days, to understand.

- Elise Atangana, Abdelkader Damani and Ugochukwu-Smooth C. Nzewi, “Producing the common,” in 11th Biennale of Contemporain African Art, ed. Aliou Ndiaye (Dakar: Secrétariat général de la biennale des arts, 2014), 21.

- Mauro Petroni, “ ‘We want to protect the spirit of freedom’ : C& in conversation with Mauro Petroni, Dak’art OFF initiator and coordinator,” Contemporary And, accessed June 30, 2014, http://www.contemporaryand.com/blog/magazines/we-want-to-protect-the-spirit-of-freedom/.

- For more on this controversy, see Anny Shaw, “Show on African homosexuality shut down after fundamentalist attack,” The Art Newspaper, published June 5, 2014, http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/Show-on-African-homosexuality-shut-down-after-fundamentalist-attack/32913.

Bio: Perrin Lathrop is PhD student Art and Archaeology at Princeton University.