“My understanding of painting is the language of abstraction, and by abstraction I mean a world of ideas, a world of complex thoughts, a world of imagination. I believe that a descriptive approach is actually arming a subject. The more it is defined, the more it is reduced. Trying to stay open, works better for me when it comes to create strong links with reality, with facts, with my understanding of what it is to paint. …”

Raquel Villar-Pérez in conversation with Manuel Mathieu

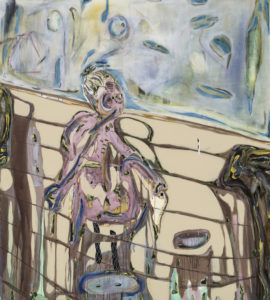

Irma, 2017, Courtesy of the artist

Manuel Mathieu.

Reflections on abstract painting and trauma

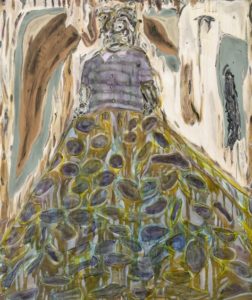

The Reception/Perpetuum, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

Reality is a complex conundrum of ideas, facts, shapes, thoughts, etc. The more reality is attempted to be defined as precise as possible by language and aesthetics, the more it is reduced into categories. To describe reality abstractly is to open the door of endless possibilities.

First of all, I want to get your eyes, you see the work, visually it catches your attention, then it gets your body, you have a physical reaction to it, then it gets your soul and your mind. For me, It has to have enough substance at all these different layers for the viewer to get closer and closer and to fully experience what is happening.

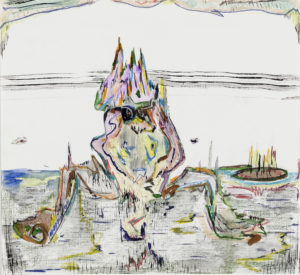

Eternal Flowers, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

It has been only under a month since Manuel Mathieu’s first solo show Truth to Power held at Tiwani Contemporary in London, closed with a remarkable sold out. The Haitian artist is already shipping works to ARCO art fair in Madrid and finalising the last strokes of his forthcoming solo exhibition at Kavi Gupta Gallery in Chicago Nobody is Watching. Manuel Mathieu’s paintings are characterised by the intuitive use of an array of soft pastel tones that inspire somehow tranquillity, combined with the organicity of gestural, and mainly, abstract shapes. The artist is relishing the reward of more than ten years of discipline and hard work. In the little temporal space in-between celebrating the success of Truth to Power and the stress of the upcoming new projects, I speak to the artist about abstract painting and trauma.

Raquel Villar-Pérez: Your artistic career took off about two years ago. What do you think was the turning point?

Manuel Mathieu: It has been an accumulation of things. When I got to Goldsmiths it took me a year to find myself, to find what I wanted to do. At the pinnacle of my experience a motorbike in New Cross, right in front of Goldsmiths, hit me. It was a terrible accident. I had a concussion, fractured my face, my jaw, lost my short time memory for a while, I almost died. My sister came to get me in London and we flew back to Canada … . It took me about 5-6 months to build myself back and start painting again. The recovery process was definitely a turning point for me because I had time to meditate and reflect.

Taking the time is important in the process of growing up. These moments when I was in limbo are very important in defining who I am and who I want to be in the world. The idea for my graduating show came from that place of reflection.

Brother I’m dying, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

RVP: Your latest project, the body of work exhibited at Tiwani Contemporary, Truth to Power, portrayed the emotional trauma left in the aftermath of the two Duvalier’s dictatorships in Haiti…. I believe the depicted scenario is very much transferrable to other contemporary contexts such as Syria, North Korea, etc. Can you expand in the ideas of atemporality/acontextuality or even universality in relation to your work?

MM: I’m sceptical when it comes to the use of the word universality; to me there is not such thing that is universal art. Art always comes from somewhere; always means something for somebody. I think an artist is due to failure by starting a project, thinking that he or she is going to achieve something universal. If something bigger then oneself is meant to happen in the work it will just happen.

This is interesting because this word is used often in the global south. However, artists from Germany, from Switzerland, from Canada for example, don’t seem to be concerned about that concept or are even asked about it. As if they didn’t have to think about that concept at all. Within their practice, the artist self-proclaims ‘what I’m doing is what it is’.

…

As an artist I think there is a capacity to dig in to very precise subjects or concerns and find elements that people relate to, it is our strength. It is through singularity that people connect and transcend reality.

At Sea, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

RVP: We tend to encounter more descriptive works, when the theme approached is trauma and violence. However, in your work you fuse expressionist figuration and abstraction, generating utterly bold compositions – why painting and why abstract aesthetics?

MM: My understanding of painting is the language of abstraction, and by abstraction I mean a world of ideas, a world of complex thoughts, a world of imagination. I believe that a descriptive approach is actually arming a subject. The more it is defined, the more it is reduced. Trying to stay open, works better for me when it comes to create strong links with reality, with facts, with my understanding of what it is to paint. … Painting is the language I understand the most, the one I feel confortable manipulating. I think certain things needed to be seen, and painting was the way for me to go about it.

Rivière Froide 2, 2017. Courtesy of the artist

RVP: Despite the unsettling theme of your work, it has something that inspires calmness and tranquillity; it may be the palette of colours used or the organicity of the shapes on the canvases. How do you manage to talk about a brutal historical situation in Haiti in a soft tone?

MM: It goes down to what painting is. I don’t associate the colours to what I’m trying to say. It is not like if I want to talk about something dark I use dark colours, or if I want to talk about something joyful I paint yellow colours. This is a very one plus one approach to painting. I don’t use the colours to charm you nor to disgust you. I’m using colours to address what I’m trying to talk in the work. I don’t want to be as black or white when it comes to the use of colours, because something can be very colourful, but bring a lot of dramatic feelings.

The way I approach it is really more about what it is that I’m painting. That’s where the questions starts from me, and based on that I organise the painting accordingly. Sometimes the content comes from an idea I have before starting the painting, sometimes it is the other way around it is the painting that is telling me what it needs. In both situations, the most important part is to stay alert to this act of appearance and disappearance.

Also, like Joseph Albers said it, a colour is never seen alone, every colour affects each other; one colour might be bright, and put next to a different colour it is altered. For me is not drama equals darkness or joy equals sunny colours. Just like reality, it is something much more complex than that.

Fedora, 2018. Courtesy of the artist

RVP: What are you working on these days?

MM: I’m completing the body of work for my show at Kavi Gupta Gallery in Chicago.

RVP: Can you expand on the show in Chicago?

MM: For that show, I am using different ways to conceptualise certain ideas that I have. When I was recovering from the accident in London, my grandmother was coming to an end. The accident brought me to the edge between life and death. Seeing my grandmother dying, I started asking myself questions – What would I leave behind? What is it that in my life, in my history I can talk about that is very singular? How the understanding of things through the lens of my own vision manifests. I decided to turn back to my life and think about ideas like history and legacy. That journey also affected my relationship with my family, in the state of vulnerability that I was, it really forced me to look into my family and the support system that I had.

These are elements that I put together, like a kind of puzzle, when I spoke to Kavi Gupta in Chicago. It was at a very embryonic stage, sort of the genesis of my ideas. He thought that it was so appropriate that I was referring to my family especially in the context of migration that is happening in the world right now. As an immigrant myself, my family is very important, it structured and contributed a lot to my understanding of this new world I was getting into.

I am currently playing in the studio with these elements: my relationship with my family, my accident, my vision of art growing up in Haiti, and certain mental states that I went through recovering.

RVP: What is art for you?

MM: Running in a large infinite field blindfolded with a smile on my face: Life.