But caught between limits of representational possibilities and the contradiction of colonial representation, here portraiture finds itself in an interesting aporia. That is between an enchanting representation, and the existential reality of knowing oneself as a problem for humanity. This performative contradiction creates problems for the lauded humanizing acts of the photograph as a general conflict in Black Chronicles IV.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja on the travelling exhibition Black Chronicles IV

Wellington Majiza, The African Choir, London 1891. By London Stereoscopic Company.©-Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Courtesy of Hulton Archive and Autograph ABP, London.

Black Chronicles IV

A Review

Humanism, be it self-critical and renewed, restores anti-black racism. A reproduction that isn’t a result of misconstrued intensions, but foundational. How than do we rehabilitate a corrupt essence? This resurgent humanism appears, instead, interested in obfuscating the status quo. In the first instance this not to a problem of particular notable acts of terror, but of the conception of “who” is the human and not, which than informs ongoing racial parity. That essential default in scholarly and creative platforms has been overwhelmingly obscured in the name of “humanizing” practices. That is, representational approaches that have, past and present, affirmed a black “human” beingness.

Recently, FADA Gallery at the University of Johannesburg (UJ) opened the traveling photographic exhibition entitled Black Chronicles IV that attests to these ocular modes of humanizing. In collaboration with London based photographic agency Autograph ABP and Visual Identities in Art and Design Research Centre (VIAD), Black Chronicles IV assembles an archive of photographic studio portraits of original late 19th century glass plates negatives re-discovered in 2014 gathering dust in a London studio. It is also accompanied by an equally compelling collection of African Americans’ studio portraits, shown in Paris in 1900 under auspices of scholar and activist W.E.B DuBois. Curated by Renee Mussai of Autograph ABP, this photographic conversation, like the 1900 Pan-Africanist conference led by Edward Blyden under the umbrella “African personality”, echoes this forge for black subjectivity. But do these images iterate this?

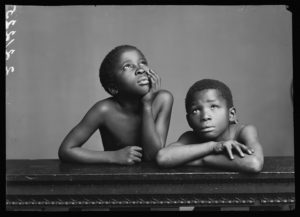

Albert Jonas and John Xiniwe, The African Choir, London 1891. By London Stereoscopic Company.©-HultonArchive/GettyImages. Courtesy of Hulton Archive and Autograph ABP London.

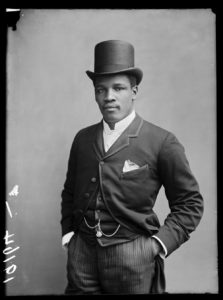

Black Chronicles IV is populated by rare but yet prominent and ordinary South African figures who have gone to become national and political symbols. Some of these images include the young Charlotte Maxeke and members of The African Choir ensemble that she was part of, before her activist’s days. As images, these portraits perform a different explicatory mission in the very quality of their representation. Arguably, they dispel the ethnographic photographic strictures, whose visual template hinges on a dubious distinction primitive Africa vs. enlightened West that has become standardized toolkit of difference. That optical register remains formative for continual reconstruction and social vilification of a blackened world.

But the same photograph, to an extent the written word, as a mediating instrument and medium of representation, indexes a latent ambivalence or slippage within colonial mo-dernity. That is photography as a generative instrument for self-reinvention. It is this propensity re-invents oneself that the photographic event for example confers to the op-pressed. This was amongst many concerns topical in the conference Curatorial Care, Humanizing Practices, to which Black Chronicles IV was the artistic culmination. Overall, the meeting seemed concerned by the curatorial and artistic possibilities that humanize black folk in spite of historical banishment from the human fold.

Charlotte Maxeke née-Manye, The African Choir, London 1891. By London Stereoscopic Company.©-Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Courtesy of Hulton Archive and Autograph ABP, London.

The representational interest of these portraits, especially Du Bois’ album, is undergirded by an impulse to portray this humanity, as supposedly imprinted on their face, speaking from “within the veil.” And how else to best eradicate the same effacement than by the same photograph, a medium whose materiality strives for illuminance, almost as if to unblacken, to humanize? Yet both portraiture, in its traditional aristocratic sense, and photography as a fracturing in the image production, seem to bolster each other here. The vestiges of elitism remain prominent in Du Bois’ choice of sitters; his crisp looking Victorian subjects who are generically fair skinned, and seem acquiescent enough to fit the declaratory measure of “the human.” In conversation with these images, is knighted British artist Yinka Shonibare’s picture quirkily entitled Effnik, which is the only contemporary photograph included in the show. It depicts a black subject dressed in late medieval regalia with his sprawling wig gently spilling over his maroon velvet coat. He stands diagonally, in a contrapposto pose; his head slightly turned and balanced on his right shoulder as he side-eyes the viewer. He takes himself serious, a vintage; a true subject of enlightenment. Shonibare’s self-portrait as a 16th century subject, anachronistically performs this pomposity of a different, if not civilized blackness, with the irony it deserves.

Jaswantsinghji Fatehsinghji, London 1887. By the London Stereoscopic Company. © Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Courtesy of Hulton Archive/ Getty Images and autograph ABP, London.

This general aura gives visual impetus to the now defunct notion of The Talented Tenth – an elite ersatz from which the excluded “rest” ought to vicariously enjoy in the name of a racialized collectivity. Indeed these images of the pristine looking blacks, culled out and differentiated from the rest, adumbrate a “striving” as Du bois would say. That is a repudiation of the stereotypic image of blackness, but also a diminution of one to an impossible copy.

The show is punctuated by wall inscriptions, some Du Boisian and others arbitrary. One such a curious line reads: “This is an archive which will bring it alive, which will make it human. Put a face to it, but bodies to it, put places to it, put clothes to it.” It is this humanization of the “it” – a thing without interiority that through a ventriloquial exteriority can re-articulate itself as “human.”

Black Chronicles IV seems to peddle an almost parallel imagery. Located in the room above, you have studio portraits of sitters in Victorian apparel, black children shown carrying gowns, wearing suits and others handling the camera or idling. These images instantiate the reach of the civilizing mission. In the room below, a different theatrics unfolds. This time not particularly contingent on their august exterior show offs or activities. A rather tentative instantiation takes place. The photograph, it appears, isn’t simply a conduit of staged humanity, but rather a medium engaged in a performative humanizing mission. These are portraits of The African Choir (1891) in individual and group contexts, including the Maxeke siblings. They are dressed in their blankets and adorned in the “traditional” head and neck wear. Re-imagined sonic compositions of the choir echo in the background. The camera seems to pay attention on the subject without traceable ulterior anthropological motives. Neither their garments and accessories nor their actual physical features appear as properties of curiosity. At least that is my first reaction: these are pretty pictures of pretty people. Their gazes on the camera give nothing less but a sense of individual and cultural subjectivity.

Peter Jackson, London 1889. By London Stereoscopic Company.©-Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Courtesy of Hulton Archive and Autograph ABP, London.

But caught between limits of representational possibilities and the contradiction of colonial representation, here portraiture finds itself in an interesting aporia. That is between an enchanting representation, and the existential reality of knowing oneself as a problem for humanity. This performative contradiction creates problems for the lauded humanizing acts of the photograph as a general conflict in Black Chronicles IV.

Alluding to the novel and its plot, Sylvia Wynter once insisted that “emporialist forces and imperialist the forces are one.” That is to say the colonial expedition and artistic enterprise are co-constitutive. Whilst the work supposedly attempts broaching assumptions of coloniality, on another side the humanist discourse attached to it, reproduces it. So even when we imagine these things as oppositional or pushed towards relative tension, the implicit logic of humanizing inhuman creates a disjuncture. The need to humanize the inhuman under the same measure of “the human” and context is dissuasive.

Thus, the unspeakable discord between representation and reality, ethically trumps the formalistic insistence on “in spite of,” if the conditions under which the re-presented subjects remain unchanged. More so, if in their reality objecthood historically extends to their beings as “thingification”. Black Chronicles IV has indeed extended to us a beautiful show of black portraits, but we are yet to truly see them as humans.