“After Feni’s initial success in Johannesburg, increasing police surveillance and interference made living in South Africa untenable.”

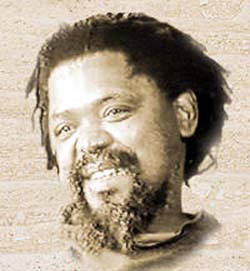

“Dumile Feni played with identities, sometimes challenging and sometimes adopting the expectations placed on the artist outside the canon.”

His work is shown in the MOMO Gallery in Joburg, till September 22.

Fragments from the article:The Dumile Feni Retrospective at the SANG

by Tavish McIntosh

Published on: Artthrob, November 2005.

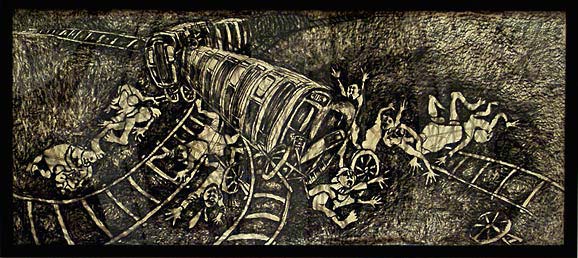

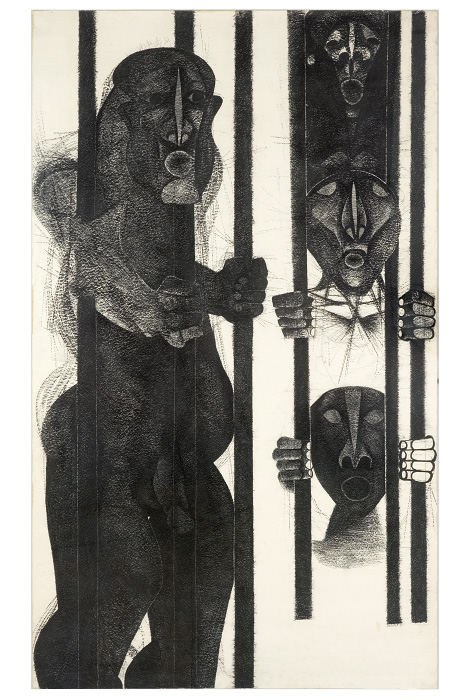

“Dumile Feni was associated with and inspired by many of the leading protagonists of a then new wave of black artistic production that arose during the 60s in South Africa. Although he never received any formal art training, he was exposed to stylistic developments of the European art world through his association with the Polly Street Art Centre. This can be seen in his use of German Expressionist techniques from 1965 onwards, as Feni worked to articulate something of the experience of urban living through this highly charged, emotive visual language. Possibly the most dynamic work of this period is done in charcoal and crayon, and Feni manipulates these media to their fullest expressive potential, playing up the drama of a situation with dark, confident lines.

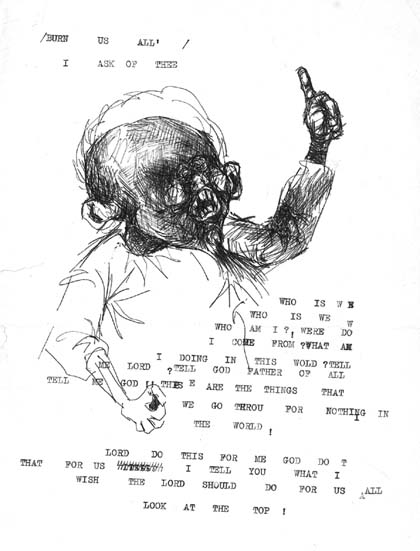

Burn us all ask o thee, 1975.

Burn us all ask o thee, 1975.

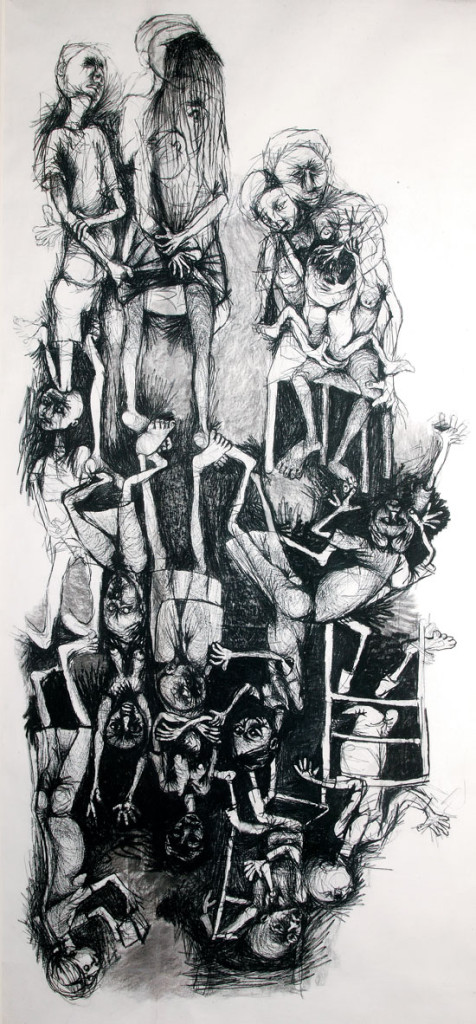

It is astounding to observe the rapidity with which Feni developed his unique brand of expression and visual vocabulary; something eloquently demonstrated by the SANG’s initial chronological arrangement. The first two rooms of the exhibition are arranged to show Feni’s stylistic developments from bland pastel sketches of township scenes in 1964, through his expressionist drawings from the next half-decade, to his more calligraphic and refined visual idiom of the later years. Feni produced both sculptures and drawings throughout his career, but it is the graphic works that show his real strength. Informed by his forays into sculpture, his later drawings focus on underlying structure and striking, graphic forms emerge from the ceaseless interweaving of delicate, fine lines. Feni’s romance of line and form string together seemingly disparate concerns, managing to seamlessly blend the sublime and the erotic with the tragic, the bestial and the lyrical.

Railway Accident, 1966.

Railway Accident, 1966.

Critically successful artistic production in South Africa was not an unmixed blessing in the 60s and living under the yoke of apartheid, to remain unmarked and invisible was often advantageous. After Feni’s initial success in Johannesburg, increasing police surveillance and interference made living in South Africa untenable. In 1968, he left for London, where he held a number of successful exhibitions. Later he crossed to the United States and lived there until his death in 1991. Feni’s negotiations with the variety of influences and contexts in which he worked resulted in striking stylistic alterations, although his fascination with the expressive potential of line remains constant.

The Classroom.

The Classroom.

Besides Feni’s increasingly expert manipulation of the graphic medium, his positioning on the borders of the Western canon and his co-option of this monolithic tradition make him a fascinating example of an outsider through his African negotiation with the tenets of modernity and Modernism. The evident influence of artists like Pablo Picasso and Kathe Köllwitz – who had themselves adopted African forms in their own work – demonstrates how Feni’s artistic vision was mediated by a European influence, and the ambiguity inherent in his adoption of African stylistic conventions. Melding forms from diverse African traditions, Feni sought to establish a position of authenticity as an urban, African artist working within the paradigms of modernist Western art – something beset with difficulties and paradoxes. The tension and pressures inherent in this negotiation result in work that is sometimes disjointed, but always extremely potent and moving.

The Prisoner, 1971.

The Prisoner, 1971.

Dumile Feni played with identities, sometimes challenging and sometimes adopting the expectations placed on the artist outside the canon. This performative notion of identity means that any simple interpretation of Feni’s oeuvre is inappropriate and our understanding is necessarily complicated by his desire to remain unfixed and forever enigmatic. Thematically the works resonate, and enriched by their juxtaposition, Feni’s concerns with religion, sexuality, maternity and metamorphosis divulge his ultimate unease with human dis/connections.”