Black art has always been around, like the Harlem Renaissance which came about in the 1920s. We have always existed within this creative space and will continue to do so.”

Jennie Baptiste in coversation with Christabel Johanson

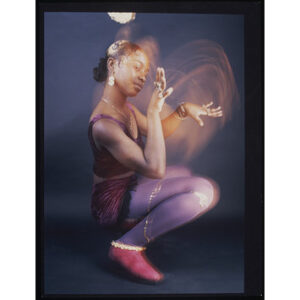

Pinky, 2002

Jennie Baptiste

London-born Jennie Baptiste has been working as a photographer for several years. Focusing on music and youth culture, her work has been exhibited in Paris, Berlin, New York and London. She has been featured in the V&A Museum, National Portrait Gallery as well as the Black Cultural Archives.

With the swelling protests around the globe, it is fitting that we catch up with Baptiste now when at the forefront of the demonstrations is the black community and its youth calling out police injustice, political inaction and social prejudices. As Baptiste’s work has been a marker of contemporary black experience, heritage and life, what does she think of this latest wave of unrest?

*

“It was hard to watch a whole mixture of emotions during this time, the brutality and rawness of the pain and injustice going on and the scale of it. It was overwhelming at times; I had to switch off from social media.” Baptiste grew up learning about racism and reading about Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr. To her they were freedom fighters. “To see it happening again more than 50 years later in real time via social media, was heart-breaking. A totally different experience from reading about it through history when I was at school and learning about it through my family.”

*

For younger generations that grew up in the 1990s and beyond, the black civil rights movement came straight from the pages of history books. However the reality of our modern world began to serve reminders every few years, each one more stark and unhidden than the last. They were reminders that jolted through the news and right into our consciousness. In 2020 George Floyd’s death was yet another tear in the thin veil of society’s illusions. For Baptiste truth-seeking and the importance of documenting real black experience, no matter how raw they are, was and still remains an important cause and a vital legacy to leave behind.

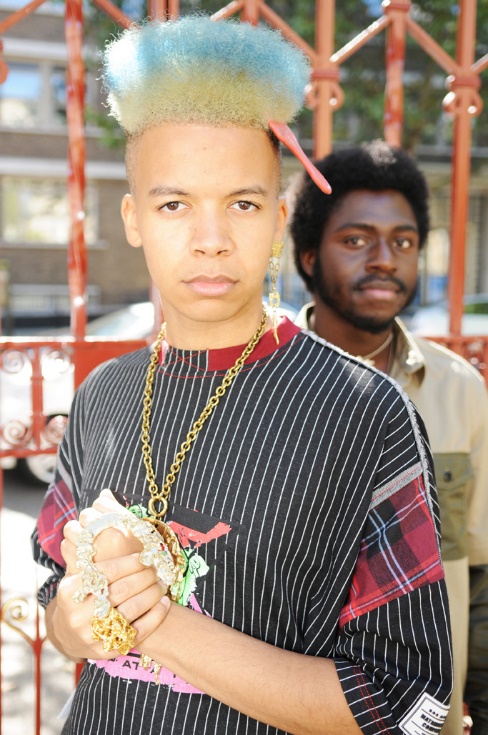

Blue Lab Beats, Jennie Baptiste, Stylist: Romario Chevoy

“[It is] a legacy that reaches generations beyond my lifetime, which I have achieved with some of my work in The V&A Museum, The National Portrait Gallery and Black Cultural Archives. Audiences will be able to explore and see the richness of our cultural heritage through the eyes of me. My photography depicts everyday people from our culture and I like to think that that resonates through my work in a way that is not always seen in mainstream media.”

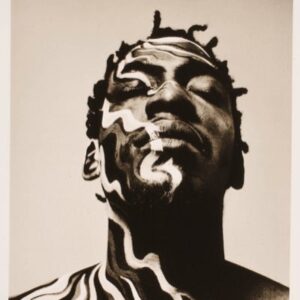

Ragga Crouching/Roots Manuva

Perhaps one of her most striking photographs is the above one entitled Pinky. Shot in 2002, Baptiste explores the merging of music and fashion in her subject who is adorned head to toe in pink. Not only did the subject only wear pink but her home was also decorated in shades of pink. Pinky’s flamboyant dress-sense reflects her lifestyle as a Dancehall Queen in Brixton and the suggestive clothing can be seen as empowering and expressive. Baptiste’s lens offers a different perspective to what would otherwise have been labelled too sexually provocative or lurid by mainstream media. It is important to understand that as a black female, Baptiste offers an intrinsically different viewpoint than the Male Gaze. Her focus was on the strength of the women, how they represented themselves and their body confidence. These are virtues that would otherwise be exalted and promoted in Feminist circles. Furthermore dancehall music and culture are an important part of Caribbean identity, with its own traditions and history which would otherwise have been disregarded as just another fad.

*

In fact as a teenager, Baptiste’s dreams of becoming a photographer were disregarded by her career’s officer. At the time raga and dancehall wasn’t being depicted in the mainstream and she was told that her project didn’t mean anything as it was about a “throwaway culture”.

Here lies a big theme and reason why preserving the past through an authentic lens in vital. Mainstream media is being revealed as more of a propaganda machine rather than an outlet for truth. Long before George Floyd’s death, the media have been accused of portraying black people as criminals and propagating harmful stereotypes of the community. This feeds society’s beliefs and reactions towards them. In particular black men have had trouble finding satisfying mainstream role models that aren’t aggressive, “thuggish” or sexually threatening. Baptiste believes the media offer a distorted representation of their lives which “can then lead to negative real-world experiences.”

*

The photographer feels like media consumption negatively effects the public’s understanding and attitudes towards black males. Whilst reflecting on her experiences working with both black men and women, she notes the potential of working outside mainstream thinking. “I have worked in photography and film with black teens excluded from mainstream classes and the results of the work that they produce is astounding. I don’t go in the classroom with a stereotype vision of their capabilities because I have an understanding of how images can be created to focus on one dimension of someone’s personality. You multiply that by a million times for a specific racial group and there you have a constructed stereotype.”

“I treat them like anyone else, the difference for them is that they are able to see someone who looks like them who they can relate to culturally so that opens up dialogue with them – especially being a female photographer; they want to know how, when and why I went into this profession and it’s always a really enlightening and empowering discussion to be able to share my experience and knowledge with them.”

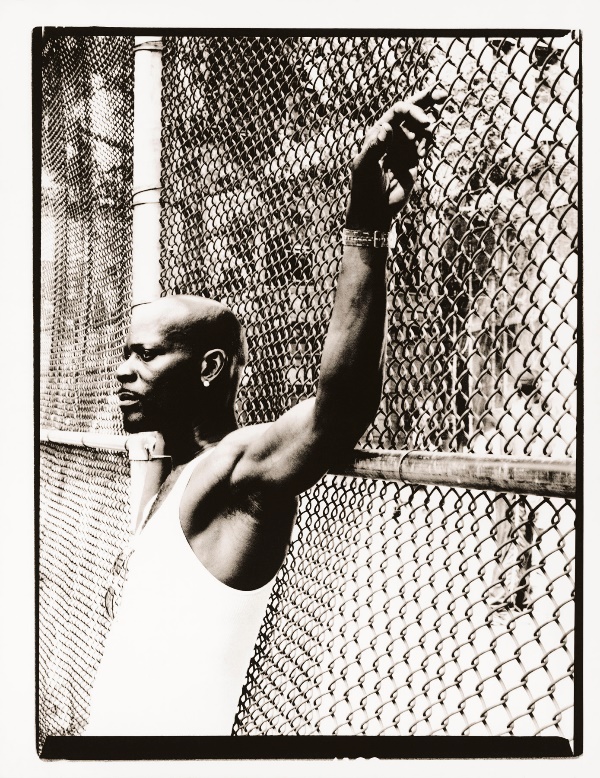

Larrick

As someone who works with the raw energy of youth culture, it is important that her portraits are anchoring for viewers. Baptiste’s work serves to inform and educate audiences on black culture, style and heritage. “I see myself as a messenger within the photographic world with the ability to give the audience a deeper understanding of the black narrative. Being a part of that I am documenting from within the culture and my images relay that affinity.”

Inspired by performers across broad creative backgrounds, Baptiste cites inspiration from Stevie Wonder, Bob Marley and Lauryn Hill as well as photographers and other artists like Gordon Parks, Albert Watson, and Derrick Adams. For her the creative importance and longevity of black art is here to stay. “Black art has always been around, like the Harlem Renaissance which came about in the 1920s. We have always existed within this creative space and will continue to do so.”

Despite the restrictions that lockdown has served across the art scene, Baptiste isn’t worried about it slowing down the spread of black artistic endeavours. “I think many artists will show on digital platforms over the next 6-9 months whilst large gatherings are not allowed. The lockdown has given creatives time to collate and strategize digital projects for the future, around the social constraints due to the pandemic.”

Estelle & Ty, Jennie Baptiste, Make-Up: Artist Bea Linton, Stylist: Chin Chinyere

As 2020 strides from month to month, we go from one headline to another. What the Black Lives Matter protests highlight is how crucial it is to capture and preserve the truth. Photographers like Jennie Baptiste offer up these authentic experiences into the archives. This is what photography and filmmaking in its genesis was created to do. This is why Baptiste’s work is educational and valuable. She channels the voices of those who would otherwise not be heard, and in the current climate this is not just a virtue – it is a necessity.