Among many other youths in Zimbabwe, Pardon Mapondera has followed this trajectory of working beyond the waithood, whether caused by the unavailability of resources or a global pandemic. On the path towards his own visual style, art wakes up Pardon Mapondera’s personal god of small things, with which he can make his “silent noise” heard.

Lifang ZHANG on Pardon Mapondera

Choda Ropa, 2020

Pardon Mapondera:

thinking with the crisis, working beyond the waithood

Since the day Corona pandemic burnt through the world, we have been forced to live in a new way. We are told to keep social distance and limit non-essential movements, as we, human beings, are now the carrier of potential danger. Maintaining personal hygiene became the protector of our lives and the prerequisite to keep society functioning. Thus, we consciously defamiliarize the ordinary and suspect the innocence of every small items we access to. As Arundhati Roy asked, “Who can look at anything anymore—a door handle, a cardboard carton, a bag of vegetables—without imagining it swarming with those unseeable, undead, unliving blobs dotted with suction pads waiting to fasten themselves on to our lungs?” However, beyond a pandemic, what does hygiene mean in one’s life, in a tradition, or in a society? What kinds of burden one or a society might carry as the cost of our uncleanliness, especially in a spiritual sense? How does that happen and how to deal with it? These are the questions Zimbabwean artist Pardon Mapondera asks through his work created during the on-going pandemic.

Todini, 2020

Pardon Mapondera was born and growing up in Chitungwiza, a high-density dormitory town about 30 kilometers away from Harare, the capital of Zimbabwe. He became very determined to choose a career of art in his teenage years. In 2015, he was enrolled for the two-year art program and graduated in 2016 from the National Gallery School of Visual Art and Design, which is the incubator of artists in Zimbabwe. Since then, he has been working as a full-time artist and has taken part in exhibitions in Harare, Grahamstown and now Cape Town. Pardon Mapondera’s art mostly focuses on his personal experiences which are entangled with the social conditions he lives in. His choices of materials often play a significant role in the meaning production of his work.

*

During this crisis of global pandemic, he speaks his mind through artwork created with found dishtowels. Right after the extremely strict lockdown moved from Level 5 to Level 4 in South Africa, Mapondera knocked on the doors in his neighborhood with some brand-new dishtowels. Encountering the neighbors’ curiosity, inquiry and at times rejection, he managed to collect some used dishtowels for his work by exchanging with them the new ones. He also went to the nearby shops, restaurants, car wash and pubs for towels. The artist explained why and how he collected the materials in our conversation:

“With this pandemic, at the shop they use the towel more. When you are in queue, they use sanitizer and wipe things with the towels all the time. I have some works way back at home with those towels but I was still learning about them. Now is the time to explore more. In this lockdown again, dishtowels are always the things at most risk of getting the virus. And dishtowels also have more memories which is attached to the human being. They collected so many information about us, like family life. Straws [which I also use in my work] can say a lot about hygiene but it’s just a metaphor. But with these ones I’m talking about our physical hygiene and spiritual again.”

Tsamba ye mayo, 2020

In tsamba ye mayo, Parddon Mapondera shaped the found dishtowels into the form of scroll which is a symbol of letter before the modern time. Connected by the red strings, they are hanging scattered among the strips of old tent, which is often a temporary shelter for humans. As indicated in the beautiful title in Shona language which means Life Is A Letter To The World, the social life of the dishtowels, accumulating its memories from a shop to a family, to a pub or to a restaurant, touched by a mother, a waiter or a child who helps with housework during lockdown, now transformed into a metaphor of our life through the artist’s creative process. What messages does one leave to the world after his/her life, a hole or a stain?

Tozvitura kunani zvamati makunamata, 2020

In another work tozvitura kunani zvamati makunamata, the intricate red strings which symbolize both life and danger create a bloody image viewed from afar. Tied by these tangled lines, the old dishtowels are transformed into the shape of hata, which means the pad African women put on their head when they are carrying something on top of their heads. According to the artist, this work attempts to visualise the burden and danger a person, a family or a society might carry without hygiene in a moral and spiritual sense. The artist is also questioning the antagonism towards traditional cleansing rituals in modern society where a new way for spiritual hygiene is not provided with the old ones being abandoned.

Installation view

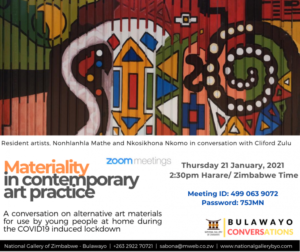

These two works, together with a few other works that talks about the similar issues in relation to hygiene, form part of the exhibition [Fig 3] in THK Gallery after Pardon Mapondera got the runner-up for the 2020 Emergence Art Prize held by the gallery. In our interview at the beginning of this year when South Africa moved the lockdown back to Level 3 due to the second wave of the pandemic, I asked the artist about his plan for 2021 that does not seem promising so far. He told me that he still has some materials and he will work with what he has and what he could find. Coincidentally, a similar conversation was happening among his peer artists back home in Zimbabwe which also returned to strict lockdown and closed its border at this time. On 21 January 2021, the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Bulawayo held an online conversation on “alternative art materials for use by young people at home during the COVID19 induced lockdown”. Artists including Nonhlanhla Mathe and Nkosikhona Kkomo participated in the talk and shared with the audiences how they created artwork with their alternative materials, such as old magazines, homemade glue, soil, fruits and leaves. I was impressed by how genuine and down-to-earth these conversations are.

It is fair to say that, this is not the first time for Zimbabweans to think and work with the conditions in a crisis. It was exactly during the social and economic collapse over a decade ago in Zimbabwe that a young generation of artists pushed the movement of working with found materials which then became a dominant phenomenon in the local artistic landscape. Instead of waiting for the situation to change, they choose “tinoona yekutamba”, to “make a plan”, using their creativity to invent new ways of being and intervening into the social process. Among many other youths in Zimbabwe, Pardon Mapondera has followed this trajectory of working beyond the waithood, whether caused by the unavailability of resources or a global pandemic. On the path towards his own visual style, art wakes up Pardon Mapondera’s personal god of small things, with which he can make his “silent noise” heard.