Artworks and projects that subtly weave in social and political awareness into a broader tapestry of our everyday human concerns have the potential to acquire more immersive and complex dimensions.

Joseph Omoh Ndukwu on Young African Artists

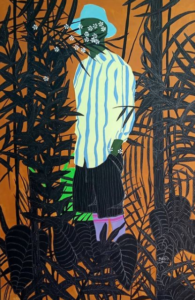

Moustapha Baidi Oumarou, Untitled, 2020

Focal Points for a Broader Imagination

In an interview at Art X Lagos, 2018, Nigerian artist and MacArthur Genius Grant winner, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, explained that politics is subtly woven into her work, but that it is through a “connection to the banality of life that everyone understands on a visceral level”. I find this thought very useful in understanding and appreciating the work of African artists, particularly young African artists in our modern (and troubled) times.

What are these artists trying to do? They are certainly not inventing new art or radical styles for rendering experience—at least not with their current works. They are invested in extending the canvas and themes of African art to embody life’s varied rhythms and intimacies. To come at the heavy themes—war, violence, politics, history, urbanity—directly is to risk being trite, to risk having a pre-packaged set of responses to your work. A serious artist tries to engage with his time with intelligence and with vision: his work must respond not merely to reality but more importantly, to the aspirations and truth within himself. Young African artists are bringing their seriousness to bear by finding a way to echo politics and the heavy themes in works that capture the complex beauty of daily life and ordinary people. The work becomes an intersection point for these thematic aims.

Richard Atugonza, Confidence 3, 2021

The sculptures of Richard Atugonza, a Ugandan artist, in his ongoing series Imperfection Perfection are sites of these kinds of intersection. There’s something almost baroque about the sculptures, but they hold back, not going all the way with their ornateness. This reluctance may be glimpsed in the rough finish and worn edges, bodies that are not quite complete, hands that do not go all the way, faces left like eroded landscapes. But the figures have distinctive features and expressions, several of them smiling, hopeful. The reluctance then is more an emotion than a sculptural technique. Hope, resoluteness, joy all emerge tentatively—but surely—out of a bleak reality, like crumbling figures pushing through walls to light. Human faces and bodies in their expressiveness and wounds become both testimony and taunt to history, become aspirational.

Looking again at his rough, pock-marked figures, subjects modelled after real people he knows, I can’t help but notice body parts that appear to have been severed off. The artist says his sculptures embrace human imperfections. Still I wonder: Are these the wounded of war? Could these sculptures be reflections on the Ugandan Bush War (1980 – 86) that left close to half a million people dead? Born in 1994, he did not live through this war, but he has had it handed to him as his history; he likely knows people, family members and friends perhaps, who lived through and possibly lost people to the war. These severed body parts, these cutting-offs—the brutality and pain of them—are almost not noticeable, subtly de-emphasized by the general wreckage of the sculptures. In Reassured (2020), a finger rests by itself on a shoulder; in Victory (2020), an outstretched arm is cut off at the elbow, like an amputation. There is always the echo of an absence, a loss—a limb, a person. Pairing these amputations and losses with the smiling or hopeful faces of the subjects throws up a kind of confusion and impatience (one is almost tempted to say, “What are you smiling for? Your smile and hopefulness doesn’t just sit right.”) However, the confusion parts a little and lets in a kind of tenderness, something almost heartbreaking.

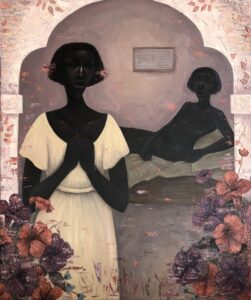

Chidinma Nnoli, A Poetry of Discarded Feelings/Things II, 2020

Bodies in artworks can remind us how broken we are in our different ways, and they can do more: they can remind us how to bear each other up through adversity, how to stand beside each other. They make us think also about what our relation to other bodies is, which ultimately is to think about our relation to society, to the world. The work of Chidinma Nnoli, a Nigerian painter born in Enugu, moves us to think in these ways. Her painting A Poetry of Discarded Feeling/Things II (2020), exhibited at the group show Orita Meta at the Rele Gallery, Los Angeles, pits women’s sexuality against a culture of shaming and hypocritical religious policing. This painting makes us begin to consider these things in the context of our own lives. How complicit are we in societal constructs—and double standards—that dehumanize women? The composition of the painting also raises a separate set of questions. In the painting a woman, hands clasped in front of her, stands in front of an alcove in which another woman, nude and silhouetted, reclines. The woman standing has an attitude of reflection and prayer, while the one reclining seems almost insouciant in her ease. Are they sisters, no? Lovers? Reflections of each other? This painting, along with the others in the Orita Meta group show, make clear that for Nnoli sexuality, identity, relationships, and self-examination are worthy concerns.

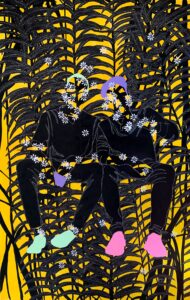

Moustapha Baidi Oumarou, Jardinier, 2020

Moustapha Baidi Oumarou, a Cameroonian artist, working in a kind of pared down realism, for his part, does something interesting with the face—the subjects in his paintings have no facial features. His paintings (which focus on family and masculinity) privilege posture, gesture and interconnectedness over facial expressions. This is a fertile point of inquiry especially in a cultural context where wearing masks—literally hiding away the face—is believed to confer a person with powers. Oumarou perhaps seeks to accomplish something similar; his skilful non-inclusion of facial features imbues the bodies and postures of his subjects with potency.

Ian Mwesiga, People and Chicken, 2020

Ian Mwesiga, a Ugandan-born artist, is another to watch. Deft depiction of skin tones, experiments with windows and traffic signs, and fluency in portraying African neighbourhoods and middle-class lives make him a refreshing break for the eye. His is not an overly intense sensibility, nor is there in his work a forced complexity. Just an artist who loves to look at his people and paint them honestly.

The three painters mentioned employ a style similar to the simplified realism of African American painter Amy Sherald. This style, gaining popularity with many young Black artists, may be perceived as an imitative weakness. Still, there is in the work and in their thematic handling an impressive facility, a certain sureness of grip.

Artworks and projects that subtly weave in social and political awareness into a broader tapestry of our everyday human concerns have the potential to acquire more immersive and complex dimensions. This is so because their impact borrows from two separate but mutually reinforcing impulses. So far, the works and artists that have been acknowledged for pursuing this kind of aesthetic are in painting and sculpture. But there is wonderful work being done in photography, film, and mixed media. I would, therefore, be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the work being done in photography by South African mixed media artist Andy Mkosi. She seems to be interested in a sincere and somewhat celebratory representation of South African townships. Whether she is photographing washing hung out in the field, or a muddy street with builders in the middle ground and dog in the foreground, or an elderly woman by a window, or a baby’s feet, or simply a shawl spread on a mattress, there is a tenderness she brings to her images. Her images evince a quality of long-interaction with her subjects, a moving patience before the shot. A number of her photographs, to be sure, are aimed at drawing attention to the struggles of queer people in South Africa and to the rights of other minorities there. But even her activism is rendered with carefully calibrated gestures.

Andy Mkosi, Beauty in the Morning (From the series There Is Beauty in Mourning). 2019

The works of these young artists step out and stretch to the external at the same time as they withdraw into themselves and attend to more intimate cares. They draw us in and become points from which we imagine ourselves more fully.