Working with technology offers too a medium for communication to audiences, particularly broader publics. Technology is a form of spectacle, a form of offering pleasure and excitement to audiences. Within the pleasure, critical ideas can be carried

Sanya Osha talks with Ralph Borland about Wire Art

Ralph Borland: An Engineer of Possibility

Albert Road in Woodstock, Cape Town exudes a mixed aura combining the old and the new. During ‘normal’ working hours, there isn’t much to say about the high-rise buildings, organized commerce, practices of everyday life and the general 9am to 5pm diurnal rhythms. As with every other major South African metropolis, there are loudly honking commercial buses (called taxis in the country) in flight or fight mode engaged in dare-devil driving. The security guards visible everywhere remind you that crime and violence are a moment-to-moment reality. Of course, nighttime in the vicinity births an entirely different scenario where all sorts of creatures spring out of the woodwork. But it is also a road where artists maintain studios to pursue their various artistic dreams.

The complex where Ralph Borland runs his studio is no different from the Albert Road atmosphere. Filled with other artists’ studios, the complex looks austere, safe and productive. I didn’t catch whiffs of marijuana or sight scraggly crowds of freeloading artists partying up a storm with their shirts off.

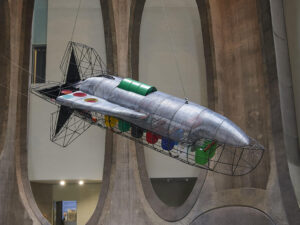

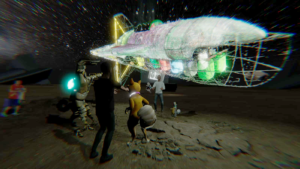

Ralph’s studio is occupied by a large spaceship-like installation that takes up most of the space. Otherwise, it remains spare and fastidiously functional. Perhaps a safe way to describe Borland is that he is a multi-media artist who strongly believes in the merits of technology for fostering understanding and social good. Meanwhile, he has taken aspects of his work into virtual reality which, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, makes absolute sense as a way to generate novel three-dimensional realities, creative interactions and experiences.

If the workman-like ambience of his studio seems so spare, Ralph’s mind, on the other hand, is buzzing with exciting creative ideas. There looms Marcus Garvey, the early 20th century Jamaican liberator of blacks with his Black Star ocean liner to transport formerly enslaved Africans back to the motherland from the New World. This idea segues into Afrofuturism and possibly a utopia defined by cosmic liberty and enlargement. There are intimations of George Clinton and the Parliament-Funkadelic collective together with the mothership connection. There are also the spirit of Sun Ra and the powerful motif of escape and celestial magnitude and infinity.

Back to reality, Borland has also been involved with street artists engaged in wire art from Cape Town to Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Brazil. He seeks to traverse the divide between academic art and street art. He is indeed besotted with technology as evidenced in his fascination with spaceships and notions of time travel.

Time itself is a thoroughly philosophical subject conceptually split as it is between the African phenomenon of cyclicity and western-defined linearity. If Cartesian rationality and Hegelian dialectics seem to be hegemonic it is possible for this perspective via only minor sleights of conceptual shift to become relative and relational. The underside of scientific cognition is primarily what informs our imaginations, dreams and neuroses. And it an underside structured by its own language and logic as Freudian psychoanalysis strongly suggests. Borland would sometimes imply that the implacable dichotomization of perception between the conscious and unconscious, the rational and irrational, can be overcome through irreverent conceptual play, non-intentional friskiness and hybridity.

This state of affairs would appear to celebrate the entombment of metaphysics including agnosticism and atheism. As a final measure, the sacrificial lamb is set free never to be sighted again. The deity is within, shrouded in the autonomous light of its own blinding independence. A comparable metaphor would be the image of a girl frolicking on a bright sun-kissed field totally ignorant of the omniscient power of her own luminous reflection. In other words, the little girl is the new self-sufficient reality, a post-metaphysical borderless being in whose unfathomable presence the universe awaits its rejuvenation and in fact, its re-creation.

In simpler terms, Borland interrogates the schism between art and science. Perhaps it isn’t always useful to maintain the conceptual separation between the two domains if only to enlarge our imaginations. Art and science constitute most of our intellectual existence and more specifically, epistemic architecture. Furthermore, in an ideal world, art and science combined form a horizontally arranged epistemological totality. But in a (pseudo) epistemic culture driven by false hierarchies, binaries and rabid technologies of domination it is often seen as necessary to maintain epistemic divisions in order to further entrench all manner of inequalities; racial, sociopolitical, economic and least of all, cultural.

At the heart of this aesthetic philosophy are yearnings for mutuality and solidarity, a social technology of care, so to speak. Indeed, mutuality and solidarity are important aspects of Borland’s practice as he often works with multiple artists with different backgrounds, specializations, expectations and material requirements. Ultimately, all that counts is realizing mutual objectives.

The question may be posed; what lies between man and machine? The minds of man and machine converge to create new realities, possibilities and also perhaps, nightmares. In this sense, stasis would appear to be a nightmare while adventure and escape offer remedies to the cultural quagmires it (stasis) creates. And so, a sorely required project for our common humanity would be to conjure a marriage of man and machine in order to birth a new ethos of being. Most probably, this would lead to a catharsis of liberty, a relentless unfurling without limits.

The idea of bricolage often comes to mind; concepts, objets d’art and objectives are seemingly whisked out of possibly thin air only to materialize like fully formed doppelgangers. Indeed, the allure of the conjurer as a shape-shifting, chameleonic entity is all too powerful. A trickster deity in the making. Totally fabricated worlds separate from mundane reality have indisputably been the most cherished ambition of current commercial cinematography. There are connections and synergies between animate and inanimate entities, at least, ideationally. These synergies promise untold and therefore unknown possibilities, the magical fruit that may or may not be rotten at its foreboding core. This seems to be the kind of universe Borland seeks to create, if not realistically, then at least conceptually.

In a world oftentimes seamlessly polarized between the rich and the poor, further objectified and banalised by hunger, squalor, disease and death, reality becomes science fiction and vice versa. Indeed, the ontologies of science fiction hold far more believable promises of redemption. And so, we’d rather leverage our bets on elusive projections as with uncontrollable visits to gambling dens. Salvation might be just a few seconds away.

Given these vortex-like conceptual linkages between art and commerce, street art and academic art, Garvey, normal science and abnormal science, Black Lives Matter, mothership vibrations, George Clinton, Sun Ra, cosmic superhighways and freedom, Borland appears to want to transform himself into an engineer of potentiality, futurity and possibility. In this interview, he further explains his ideas and efforts to realize them.

What are your initial motivations and inspirations for working on wire art?

I made my first – actually my only – wire car when I was about 14 years old, in Harare, Zimbabwe when I was at high school. I had seen wire cars around me, probably for sale in the streets, as well as being pushed along by kids; they were a popular image of Africa as well, so reproduced in films, TV and in print. I wanted to make one myself, and made a small Citroen 2CV – there was a 2CV that drove around Harare, and I thought it was a great little car. I also made jewelry with copper wire, and scooby wire (telephone wire) when I was a teenager. Scooby wire jewelry was a popular style, probably based on work from KwaZulu Natal. It was part of identifying with an African identity too for me I would say, in the politicized environment of the 1980s and 90s in South Africa and Zimbabwe, learning to make vernacular popular culture items out of available materials, and to adorn myself with them. I think this is part of teenage identity formation, to want to acquire and wear symbols of belonging.

As an adult, and after many years of studying and making art, my interest in wire art remained. It’s about an interest in making – how people use materials around them to depict the world; and in the context of street wire art, how people make a living from making and selling art. My interest in art has always been broad, and I like to identify (or I identify with) modes of creativity outside of the art world as well as within it. I’m fascinated by how techniques and ideas get passed around – how do kids tell the same jokes, play the same games or sing the same songs in different locations? How is it passed on? With wire art, I could see something similar happening: the same or similar forms made in different places. I noticed particular stand-out designs, like characters from movies, which became popular and proliferated. I wondered if I could catalyze new designs in the street wire art scene, which if they were popular would get carried through the network like a virus.

How has been the experience so far? The highs, lows, dashed expectations and triumphs? Would you like to comment on that?

The high point in this project has been the realization of Dubship I – Black Starliner (2019 – ongoing), the giant music-making spaceship sculpture we installed in the largest contemporary art museum in Africa, the Zeitz MoCAA in Cape Town in 2019. This was the first demonstration of the scale of our ambition for the project, and it was a real labor of love, with blood, sweat and tears gone into its production. It came about thanks to a coincidence of opportunities: a grant from the National Arts Council of South Africa, and the offer to show the work on an Afrofuturist art exhibition at the Zeitz, courtesy of their acting director at the time, Azu Nwagbogu. We had 3 months to go from an idea on paper, to the fully-realized piece. I knew the only way I could do it was by pulling together a team, and running this in the way I imagine a film gets made: with a team of specialists working together. I allocated the budget, asked people for advice, and assembled the team.

Crucial was entering into 3D-modelling and Virtual Reality, starting with scanning the atrium of the museum where I proposed to hang the work, and using this to design the work in response to the space. My collaboration with Jason Stapleton started then, and we’ve worked on a number of projects since. Other collaborators included musicians and instrument-makers, electronic engineers, welders, painters, industrial designers, and of course wire artists. Having wire artists working on the sculpture in the center of the museum was a real achievement for the project, as bringing wire art into the establishment and having it celebrated, elevating its status in the art world, is on the of the goals of the project. Craft and vernacular street forms challenge the art world, and particularly in South Africa bringing an art form that some people would associate with ‘airport art’ and tourist kitsch into contemporary art spaces sets up a friction with the establishment. I was happy to see the wire artists I work with feeling their access and status enhanced by this opportunity.

The low points have probably been around friction and sadness in relationships within the project. I’m thinking of one period in particular of estrangement with an artist on the project, which has since been resolved, and the relationship strengthened as a result – but at the time it was very hard. Working with talented artists means working with temperamental people; often the people with a lot of vision and creativity are also difficult to work with – or one has to learn how to work with them. As an artist myself, I understand this well, as I also experience the anxieties which can sometimes dominate one’s life, and the way in which working with others can sometimes be a strain on one’s own desire to do your own thing. Money and the need to make a living place additional strain on these relationships; the rift that I’m thinking of came about when I was dead broke, but still wanting work from one of the wire artists I’m close to, to respond to an opportunity – and I couldn’t get what I wanted from them.

That’s been a vulnerability in the project: I’ve often been in a vulnerable position myself as a self-employed artist, trying to make things work with very little resources, and prioritizing responding to opportunities for visibility without having the means to support it. Sometimes that’s put strain on relationships, when I’m trying to find the means to support other vulnerable self-employed artists, though I’m in a similar position myself; and in that situation, friction and mutual dissatisfaction can spring up, cascading through the network: a domino effect, or a snowballing of fucked-upness It’s hard to be a provider when you don’t have enough for yourself. That’s one reason why I’ve sought more stability for myself by finding other work, so that I can provide more stability for the project and the people I work with – so I don’t get sucked into the cycle of stress and need that can threaten our work. Fortunately, through working together for several years through the highs and lows, and through all of our acknowledgement that we have to support ourselves, we have attained more peace and trust between ourselves.

Can you discuss some of your conceptual and theoretical antecedents as an artist?

I feel a lot of affinity with Interventionist Art practices. This is based in the work of the Situationists in the European avant-garde of the 1920s, which has been reworked over subsequent decades – in politically engaged art practice of the 1960s, and into the 1990s, and till now. Fundamental to Interventionism is the idea that art can live in the world, not just in art galleries; that art is not just about representing the world, but about intervening in it, creating change in the world. My work with wire artists is a kind of intervention, in that I saw something happening, a form of practice, or a community of practice, in public spaces, in the street, and wanted to get involved: to collaborate, to intervene, to influence. Interventionism has taken on a particularly direct political character in the South: one of the influences I cite is the work of the Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles, who was active in the politically repressive period of military dictatorship in Brazil in the 1970s. His project ‘Insertions into Ideological Circuits’ involved putting messages of resistance into clandestine circulation: on recyclable Coke bottles, and on money. Other European avant-garde art forms such as Arte Povera from 1960s Italy, which makes use of cheap, non-art materials, find particular expression in the South: such as in the art made from waste materials found across Africa.

One of the first art periods which really turned me on was one of the first I learnt about in art school, studying at the University of Cape Town back in the 1990s. We learnt about the Realist painters of late 19th century France, with Gustave Courbet one of the iconic figures. What distinguished their work was their depiction of everyday contemporary reality rather than the idealized world of mythology, or of royalty. They particularly depicted labor: workers. This depiction of the ordinary and the everyday is important to me too; this valuing of everyday experience. To be a Realist in art is inherently to be political: because to strive to depict the world as it is means to show its injustice and inequality; whereas focusing on depicting sanctioned subjects considered worthy of celebration by the establishment – kings and queens and military heroes – risks glossing over society’s less savory aspects.

African Robots Series

I relate to the figure of the artist as someone who wants to identify certain features of society, and work out compelling way to bring this to people’s attention. I’d think of this as playing a critical role, and on learning about modes of communication. This ties in with my interest in technology. I’ve been interested in technology since I was a child, because invention and technology are also sites of imagination and creativity: how can one imagine new ways of doing things, machinery that can accomplish fantastical things, science as a form of magic, and so on. I’m excited by the potential for invention.

Working with technology offers too a medium for communication to audiences, particularly broader publics. Technology is a form of spectacle, a form of offering pleasure and excitement to audiences. Within the pleasure, critical ideas can be carried. I’ve engaged with popular culture, intimately connected with changing technologies (recording and transmission technologies for music, visuals and other forms of information) since I was a child, taping songs off the radio on the kitchen floor of my family house. I started DJing and organizing parties when I was at art school, and that’s something I do to this day. I have a regular online radio show, I collect music, and I go to parties and love to dance. I’ve had communities in the nightlife world since I was a teenager, and wherever I go in the world, I plug into scenes whose vibe I connect to. This finds expression in my art, which plays on sound system culture and popular culture, Dubship I – Black Starliner being an expression of the interest in reggae and dub I share with the wire artists I work with. Zimbabwe is a regional center for reggae culture, and something we’ve all grown up with.