In the end I discovered a show making bold social commentary – speaking to the past, the contemporary and the future of Zambia, if not Africa.

Barnabas Ticha Muvhuti on an untitled exhibition with works of Aaron Samuel Mulenga and Mapopa Hussein Manda

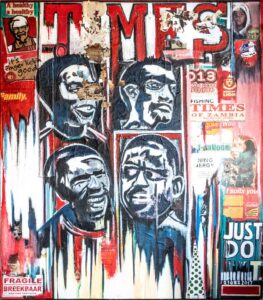

Aaron Samuel Mulenga, I can’t breathe, 2021

Searching for patterns of resemblance in parallel:

Aaron Samuel Mulenga and Mapopa Hussein Manda in the FNB Art Joburg 2021

While viewing Modzi Gallery’s exhibition in the FNB Art Joburg 2021, showcasing the work of Aaron Samuel Mulenga and Mapopa Hussein Manda, I found myself drifting and wandering in search of points of intersection and divergence. Evident at first glimpse were parallel themes like the politics of climate change and ancestry, punctuated by a marked difference in materiality, styles, and symbolism in the untitled show. Yet I understood that pairing two artists in a show or juxtaposing their work generates dialogue, if not multiple ones. As such, I appropriate the title of this essay from writer Rebecca Solnit’s In Praise of the Meander (1), an essay I have engaged with whenever my mind oscillates ‘back and forth’ in pursuit of a linear narrative. Reflecting on it always licenses me to wonder, even go wild in my waking dream, searching for common elements. In the end I discovered a show making bold social commentary – speaking to the past, the contemporary and the future of Zambia, if not Africa. The beauty of not assigning a title to a show is that it frees art from the burden of ‘meaning’ and gives viewers the liberty to interpret it however they want. (2)

Mapopa Hussein Manda, The 1960 Murder of Lillian Burton, 2021. Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 100 cm

Both Mulenga and Manda revisit the nation’s archives referencing selected events. In The 1960 Murder of Lilian Burton, a portraiture painting collaged with newsprints, Manda highlights the harrowing May 8, 1960, incident in which a white housewife and her kids had their car doused in petrol and set alight by a mob in Ndola. Depicted in the portraits are John Chanda, Robin Kamima, Edward Creta Ngebe, and James Paikani Phiri, four UNIP (3) members who were tried for allegedly masterminding the attack, in what is considered the longest and most costly trial in the legal history of Northern Rhodesia. The incident strengthened the settlers’ resolve to consolidate power, yet also intensified the nationalists’ fight for self-determination.(4) In his analyses of ochlocracy, novelist and critic Teju Cole states that mobs, characterized by their quickness, do arise out of a crises.(5) It is that context Manda does not want Zambia to forget, as well as the strange fact that on her deathbed, Lilian did not want the Rhodesians to avenge her death.

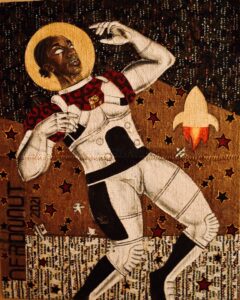

Aaron Samuel Muleng. Afronaut Jojo, 2021. Fabric Acrylic on Hessian, 100 x 125 cm

Although Afronaut Jojo and Afronaut Chintelelwe are Afrofuturistic works asserting Black liberation and aspiration, in them Mulenga also references the 1964 Zambian Space Program initiated by Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso, a man who seemingly had a vision well ahead of his time and that of a nation whose citizens questioned his sanity at the time. “When certain people speak others listen, as long as they are not the marginalized,” exclaimed Mulenga. Nkoloso was not deterred by those who thought his was mere wishful thinking, declaring instead, “But I’ll be laughing the day I plant Zambia’s flag on the moon.” (6) The artist also wants us to engage with the seemingly disparate objects he incorporates in the frames, mostly drawn from the “witchcraft sections” of anthropology and ethnographic museums. For how long the European knowledge system will continue to vulgarize masks and other objects originating from Africa is a matter that troubles Mulenga.

Zambia recently lost its first president Kenneth Kaunda, considered one of Africa’s great statesmen. Both artists memorialize him in interesting ways. In Welcome Home KK, Mulenga uses a mask borrowed from the Chokwe ethnic group, marked with the icingelyengele symbol. Most notable in the work is a replica white mouchoir, symbolizing the late former president’s trademark handkerchief. According to the artist, “KK has had great moments for the nation of Zambia, and for the continent of Africa too. So, I saw it befitting to pay tribute to him.” It was while in Mbala, an area of rich histories and natural beauty in northern Zambia, that Mulenga seriously thought about the subject of the ancestors of the land and conceptualized the work. By passing Kaunda transcended to become one of them.

Aaron Samuel Mulenga, Welcome Home KK, 2021.Sculpture Handkerchief with Hessian on wooden plinth, 13 x 9 x 8 cm

Mapopa Hussein Manda, The Zambian Last Supper, 2021. Acrylic on canvas, 150 x 300 cm.

In The Zambian Last Supper, Manda draws inspiration from Leonardo Da Vinci’s iconic work to also pay tribute to a leader who served the nation of Zambia with distinction. “The idea came seeing that KK was quite advanced in age and the inevitable would happen. I asked myself how I would immortalize him?” explains Manda. In the portrait, the artist includes all of Zambia’s past presidents, and the incumbent, and a few key liberation heroes, with Kaunda occupying center stage. The portraits of the leaders are collaged with headlines from the nation’s newspapers. The food and drinks on the table are not random. They either depict the nicknames for some of the leaders or the lavish lifestyles they were known for. The work is an embodiment of postcolonial Zambia’s history seen through the nation’s presidium, yet it invites the viewers to reflect and laugh at some of the flaws in the characters that have occupied the nation’s highest office over the years. Filled with humour and biting social commentary, Manda’s work compares better to a work of the same title by Uganda’s Paul Ndema. (7)

Mapopa Hussein Manda, Hope and Extinction, 2021. Acrylic on Chitenge and Hessian, 258 x-256 cm

The two artists also engage with various key contemporary issues in interesting ways. In Hope and Extinction, Manda takes on environmental issues. The artist, who is a member of Extinction Rebellion which is a global environmental movement using nonviolent means to compel governments to tackle causes of climate change, sees it befitting to use Zambia as the launchpad for his contribution to the noble campaign. The nation has witnessed the destruction of arable land and pollution of underground water systems through abandoned mine dumps on the Copperbelt. “Contrary to what capitalists think, mines are detrimental to society. Zambians deal with the toxic waste emanating from the detritus of mines,” asserts Manda. The timing of the work could not be greater, with the just ended 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference – COP26, exposing some of the leading global powers for being out of touch with the threat climate change poses to humanity. For Africa, the threat is immediate. Also speaking to the idea of standing up and acting is Mulenga’s Sanga Ishiwi Yobe, which translates to ‘Find Your Voice’. The artist calls the youths on the continent to stand their ground and participate in the formulation of the decisions that determine their future. In the recent presidential elections, the youths of Zambia did that and made sure the election was not rigged or stolen from them.

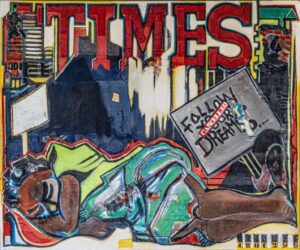

Aaron Samuel Mulenga, The Proletariat ,ca.2021. Sculpture Worker’s helmet with wooden plinth, 12 x-7-x 9 cm./Mapopa Hussein Manda, Dead Aid, 2021. Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 120 cm

Employing found materials in the form of a mask and an industrial helmet in The Proletariat, Mulenga pays tribute to the Black workers in different trades. The work is the artist’s way of celebrating Black success, which mostly comes through toiling. “Always remember, we are our ancestors’ wildest dreams. Our grandparents and parents have been through a lot to put us where we are, sometimes with no food to eat. They paved the way. So, we just cannot sit on our laurels,” says Mulenga. Perhaps, there is a serious dialectic pursuit when one juxtaposes Mulenga’s work with Manda’s Dead Aid, which engages the emotive matter of western aid and its effects on the developing nations. Manda perceives western aid as “a neo-colonial agenda to keep the developing world from realizing actual development.” In the work, lying on the ground is a woman possibly swooned by poverty. In the backdrop is a message derived from Banksy: “Follow Your Dreams: Cancelled”. I invoke the name of Dambisa Moyo, Zambia’s famous writer on the subject. The artist thinks she could perhaps do more if she was not the poster-girl of the west.

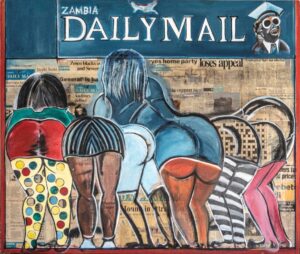

Mapopa Hussein Manda, Bend Down Boutique ‘Salaula’, 2021. Acrylic on canvas, 100 x 120cm

In the same way western aid has destroyed Africans’ industrious abilities, the importation of secondhand clothes from the east has destroyed the local manufacturing industry. This is the narrative depicted by the artist in Bend Down Boutique ‘Salaula’. “Some buyers dress as masquerades to try and hide themselves from the public gaze,” says Manda. ‘Salaulas’ are places where some customers manage to fish out the latest fashion and sports labels as well. In well-functioning economies, governments would impose protectionist policies to ward off external competition for the local industries. However, this is not the case in most African countries characterized by high levels of unemployment, with an underpaid civil service.

Aaron Samuel Mulenga, Sanga Ishiwi Yobe, 2021. Megaphone on wooden plinth, 12 x 20 x 14 cm./I Can’t Breathe, ca. 2021. Sculpture, Gasmask with Burlap on wooden plinth. 12 x 13 x 7 cm

Mulenga’s I Can’t Breathe engages with the condition of precarity Black lives are subjected to throughout the world. In the USA, the experiences of the Black subject are not a secret anymore. Blacks who have endured the perilous journey from the motherland to Europe find themselves on the fringes of society. Even on the continent, the typical postcolonial government is not friendly to its Black subjects. Even when read as signifying the moment we are currently in – the time of the pandemic – it is the Black subject that has endured the most in many parts of the world.

Besides the identified themes above, there are other aspects to consider in this exhibition. The materials the artists employ in executing their ideas are worth discussing too. Mulenga has developed a repertoire of using hessian, and the icingelyengele symbol, which he has discussed before. (8) As such I asked him about the mask. “It comes from the Chokwe people found in Zambia, Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Although I acquired the masks in this work from the market, that does not make them less authentic. This is something I would want the audiences to interrogate.” Likewise, Manda draws my attention to the reclaimed wood he uses, especially for the works that engage environmental matters. “Certain subject matter demands certain materials,” the artist states. His use of newsprints in the collages can also be read as a way of upcycling.

Again, the big lesson from Rebecca Solnit is that it is alright to meander when not certain, for structures do take many forms. I see this body of work highlighting past legacies, engaging with current contentious issues, and speaking to the future of Zambia, Africa and the world. However, as Teju Cole asserts, “… in discovering all that can be known about a work of art, what cannot be known is honored even more.” (9) I admit there could be a blind spot in my interrogation, knowledge, and understanding of the work. Like any other, this exhibition can be read in many ways.