This article is a commentary on the Ridder Thirst LP, a double 12” vinyl record produced by artist and writer, Abri de Swardt. A remarkable project.

The record includes commissioned tracks by artists, student activists, curators, academics, musicians and writers in response to the state of tertiary education at Stellenbosch University amidst the rise of student protests taking place at the University of Cape Town and the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg.

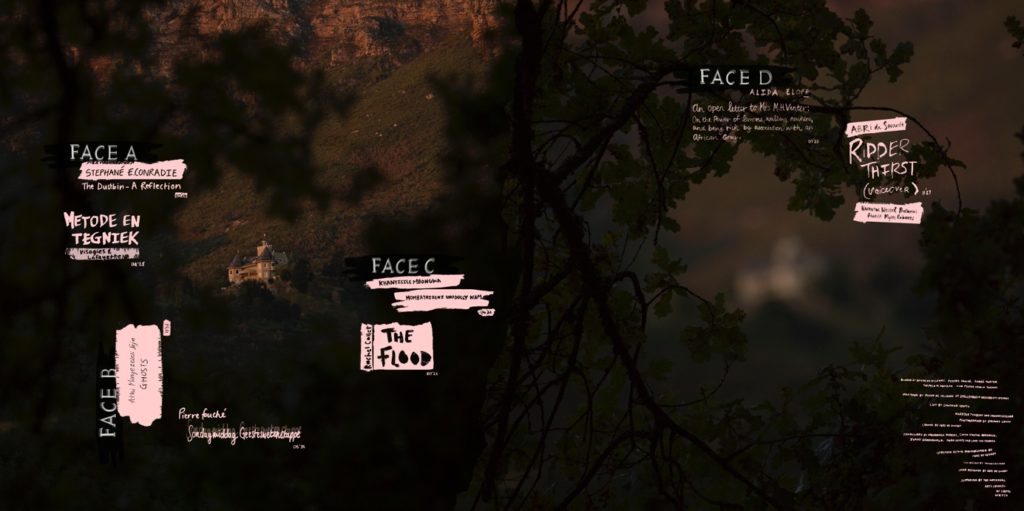

Each of the four sides of the record presents two tracks in dialogue, pairing divergent formats such as judiciary documents, punk music, the lecture, the fable, spoken word poetry and paralinguistic expressions, to foreground listening as political act.

Bhavisha Panchia on Abri de Swardt’s project Ridder Thirst LP

Abri de Swardt, Ridder Thirst (still)

Abri de Swardt: Ridder Thirst LP

Ridder Thirst LP (2016 – 18), with Stephané E. Conradie, Metode en Tegniek, Athi Mongezeleli Joja, Pierre Fouché, Khanyisile Mbongwa, Rachel Collet, Alida Eloff and Abri de Swardt, Double 12’’ Vinyl Record, 62’40 min. Installation view Ridder Thirst, POOL, Johannesburg, 26 April – 17 June 2018

Ridder Thirst

Ridder First

River Thirst

River First

First River

Eerste Rivier

Slippages, mis-translations and mis-readings are what contemporary artist Abri de Swardt, alerts our ears towards. I take the title of the 12-inch LP, Ridder Thirst (2016 -18) as a provocation, not only raising caution against simplified interpretations, but also reminding us that oftentimes histories, events, and experiences cannot be solely ascertained from a single, homogenous vantage point. The slippages across vernaculars and positionalities, force upon us an acknowledgement of the conditional status of reading and listening, and how we are often situated within and against discourses with which we identify. This is what Ridder Thirst LP attends to: a score of voices and opinions (racial, class and gendered) which register subjective multiplicities, in a country fraught with legacies of white settler colonialism, slavery and apartheid.

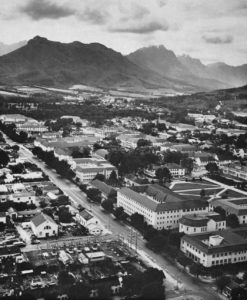

Stellenbosch and Stellenbosch University specifically are De Swardt’s sites of enquiry. The city basks in the hum and tranquillity afforded by former systems of oppression – an affluent veneer of grandiose properties and pristine gardens. Underground, lies the stories of slaves, rebellions and ruin. Black bodies have been at the mercy of white monopoly capital since Dutch Governor Simon van der Stel fell deeply in love with the ‘land’, and established the Colony in 1679, along the banks of the Eerste Rivier. The planted oaks that line the city streets witness blatant racist attacks and micro-aggressions against black students and residents. It is a site in which historical forces beat against the present; a site where the future fails to arrive. Stellenbosch is a microcosm of the nation state, in which the critical masses contest, debate and legitimate claims to land, language, memory and heritage. The historical legacy of Stellenbosch University in particular, is steeped in white Afrikaner national politics: it is the university where theories underlying the Nationalist policy of apartheid were outlined by a group of professors, who would be the founders of the South African Bureau of Race Relations in 1947.

Alice Mertens, The university buildings, grouped together on the foot of the Jonkershoek Valley, have retained the bright white-washed exteriors, traditional to the Cape, from Stellenbosch (1966, Nasionale Boekhandel: Cape Town)

Ridder Thirst LP’s assembly of voices and positions, bring together eight audio tracks in conversation with De Swardt, during the FeesMustFall protests/movement in Stellenbosch in 2015. The pieces respond to the state of tertiary education at Stellenbosch University amidst the rise of student protests taking place at the University of Cape Town and the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Audio pieces by Stephané E. Conradie, Metode en Tegniek (band), Athi Mongezeleli Joja, Pierre Fouché, Khanyisile Mbongwa, Rachel Collet, Alida Eloff and the artist himself, range from official testimonies and narrated events to non-verbal utterances and musical arrangements. These recordings vary formally in texture, grain and pitch, and employ different vernaculars which traverse with ease. The student-led protests in Johannesburg, Cape Town and Stellenbosch were catalysts for conversations and debates concerning land reform, a spiralling economy and inadequate knowledge systems on a regional and national level.

This ensemble of voices reminds us that the voice is a material, sonic and aesthetic production, representing the life of the body of the individual and its capacity for expression. Douglas Kahn (7) argues that the voice is “the most widespread private act performed in public and the most common public act experienced within the comfortable confines of one’s own body.” For scholars such as Rosi Braidotti, “There is something about the voice, isn’t there, something special. It’s the acoustics, the sonic footprint of the soul of the person that expresses.” (1) Conversely, disciplines such as voice and sound studies have discursively taken the voice as the ultimate cue of estrangement from the body, leaving the voice autonomous to the body that produces it. Such a disassociation of the body from the voice operates differently and holds different repercussions depending on what body you occupy. (2) As a social and material phenomenon, the voice is the medium through which declarations are made, a medium for self-realization and self-assertion, individuality, authorship and agency. It is a force which is mediated, recorded and played, as in Ridder Thirst, leaving its acoustic traces, embodied memories and associations with us.

Members of Open Stellenbosch protest next to the red carpet at the inauguration of Stellenbosch University’s new vice-chancellor, Professor Wim de Villiers, 29 April 2015

Pressed onto two transparent vinyl records, these eight tracks are housed in a jacket designed by De Swardt, featuring images of excess and indulgence: two women are adorned in jewellery, and crowns made of collaged pictures, exhibiting wealth, decadence, excess and sovereignty. These pieces of jewellery were created by Mouroodah Darries, Carla Maxine Germann, Joani Groenewald, Nora Kovats, and Lani van Niekerk, all graduate of Stellenbosch University’s Visual Arts Department. Each carries with them a glass of wine; their glances of indifference express class affluence. The image of Herstein Estate and the Bavarian-styled castle located in Jonkershoek, Stellenbosch is featured on both inner covers of the gatefold. The architectural style of the castle has been described as a ‘contemporary fantasy castle’ in the “Heritage Survey: Stellenbosch Rural Areas”, whose authors further describe the castle as, “an alien element in the cultural landscape, sited obtrusively where it is visible from many surrounding viewpoints.” Highly visible and unsympathetic to the character of the winelands, the castle offers a clear example of the intrusion of white settler colonialism and the disregard towards the land and its inhabitants. The Eerste Rivier is another key site from which De Swardt found interest. He draws upon the work of Alice Mertens, a Namibian ethnographic photographer who captured indigenous peoples of Southern Africa, including Stellenbosch and its inhabitants during apartheid. Mertens was also one of the first lecturers of photography at Stellenbosch University. Resonant for De Swardt were Mertens’s images of Stellenbosch University students/lovers rendezvousing on the bank of the Eerste Rivier, which speak to the relationship between land, desire, pleasure and entitlement during the 1960s-70s and today.

Ridder Thirst LP (2016 – 2018), 12” vinyl gatefold front and back cover designed by Abri de Swardt; Marijke Tymbios and Jeanne Gaigher photographed by Strauss Louw, featuring crowns by Abri de Swardt, and jewellery by Mouroodah Darries, Carla Maxine Germann, Joani Groenewald, Nora Kovats, and Lani van Niekerk

The Record

The vinyl record is a site in which data can be stored, inscribed, archived and retrieved. Within the tacit grooves of the vinyl record, lies a repository of encoded information. The introduction of Thomas Edison’s phonograph in the late nineteenth century introduced new possibilities for aural mediation, and shifted communication and listening practices. Arguably, it was the first instrument to reproduce sonic phenomena in the sense of “rephenomenalizing them or playing them back” (Feaster 139). Audio that could travel across time and space would open the world up to people and cultures that were previously inaccessible. This writing of sound into history is the “project of embodying the transient motion or perception of sound itself in writings as enduring objects.”

Phonography, the combination of the Greek phone (sound, voice) with graphe (writing) meaning sound-writing, or voice writing, is to embody “the transient motion or perception of sound itself in writing as enduring objects” (Feaster 137). De Swardt’s decision to use audio as both a site for expression and carrier of information is not incidental. In recording these audio pieces, De Swardt is creating a record for futurity. It is a vessel that carries these notes, letters and sonic remarks across time. Acts of recording are acts of space making. In recording these audio pieces, they are given material precedence and a physicality which could otherwise easily slip through data streams online.

Stephané E. Conradie, The Dustbin – A Reflection, 07’16 min, Ridder Thirst LP Face A

Ridder Thirst LP opens with Stephané E. Conradie’s soberly reading a letter she wrote that was addressed to the Magistrates Court for a student protest (a call to action by students demanding free education) in which she participated and was arrested for malicious damage of public property on 23 October 2015. The letter was mandated as a form of punishment, an act of repentance demanding her to reflect on the consequences of her actions, in this case, the setting alight of a dustbin. Fire is no stranger to South African protests: protesters and disgruntled citizens have set trucks on fire, buses on fire, foreigners on fire, Ubers on fire, books on fire, artworks on fire, and dustbins on fire. Fire is what protesters use as a call for radical action. “Can any decision in South Africa be made without violence?” is a question Conradie leaves us with. Testimony was a crucial form in facilitating processes of healing in post-apartheid South Africa. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) initiated in 1995 was formed to aid and advance reconciliation of human rights abuse carried out during the apartheid regime. While there have been critiques of its effectiveness in bringing about actual justice, it nonetheless became a key site for the sharing of grievances. They created a space for abuses to be heard and acknowledged.

Ridder Thirst LP (2016 – 2018), 12” vinyl gatefold inner spread designed and photographed by Abri de Swardt, font design by Monique Biscombe

South Africa is built on multiple forms of violence: material, psychological and epistemological. Responding to these persisting legacies is Khanyisile Mbongwa, who recounts a racial incident that took place in Stellenbosch when a couple of black female students from Stellenbosch University were celebrating the end of their exams. In Mombathiseni Unodolly Wam Mbongwa narrates the incident on behalf of one of the students who is unable to tell it herself. Despite the victim’s absence in the telling of events that transpired, the story is told through another’s voice in resistance to being silenced, to give precedence to narratives that would otherwise go untold, and thus unheard. Switching between English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa, Mbongwa’s voice is strained in anger, yet remains defiant; her tone is unwavering and unapologetic. Her voice carries with it the violence and terror of that night.

“I’m sick of you blacks acting like this!” screams a white Afrikaans student at the group of female students. This statement is telling of the social and spatial dynamics affecting black bodies in Stellenbosch. Who sets the norms for existence and behaviour? And whose body and action is rendered deviant to those established norms? Dominant cultures dictate the default, the system in which the subjugated group must succumb. Eurocentrism is a clear example of world-making, which wilfully disregards any societal or cultural forms which lie outside of its norms and conventions. The same applies to language under colonial rule, and white settler colonialism, reminding me of Andrew Putter’s video installation Secretly I will love you more, that looks to the violent erasure of the Nama language by the Dutch settlers who forced indigenous people such as the KhoiKhoi to speak Dutch. Anti-colonial scholar Frantz Fanon pointedly wrote in Black Skin, White Masks (17-18), of dynamics of language as a cultural and material form, to understand the violent effects of colonialism and racism on society. What is it to speak in the tongue that wields power? Quoting De Swardt (36), “Afrikaans not only became emblematic of the enunciation of racist violence, but constituted racism and violence in and of itself.”

Non-verbal utterances in Pierre Fouché’s Sondagmiddag Geesteswetenskappe captures the thrust of desire, pleasure and intimacy. We hear rapid succession of skin touching, slapping; of hands slipping. Subtle breathing increases gradually, as spontaneous bursts of pleasure are vocalised. This is an encounter of eros and […]; an ensemble of “blissed-out sound of broken down speech”, where “bliss interrupts language” (Corbett & Kapsalis 102). Like De Swardt, and many others on the record, Fouché completed his studies at Stellenbosch University. His artistic practice explores and challenges gender normatives through intricate lace, rope and needlecraft for example. In Sondagmiddag Geesteswetenskappe the chosen medium is the body as a site for the production of desire and pleasure, and extra-lingual vocal sounds. This recording of a five person, all-male, circle jerk is relayed through the sensual cacophony of utterances and punctured breathing that extends beyond the threshold of gender, sexuality and normativity.

In the speculative narrative The Flood, Rachel Collet offers us an impression of Stellenbosch submerged in water, after continuous rains cause the Eerste Rivier banks to burst. Through the recollection of detritus that resurfaces in the surreal, Collet paints a disorientating image of the university through a number of objects that are visible once the water levels recede. The imagery she conjures is lucid and precise, as she imagines the debris of the university. Library equipment, artwork, thesis books and paper are strewn across the university’s campus. A diary of confession is found in which sexual encounter is recorded, a flip file of worship songs. As she recites some words in isiXhosa, we hear the struggle for familiarity with the language and its words. To return to her speculation, what would it mean for Stellenbosch to be washed away, or for all its secrets and histories that are buried in the wine farms, or at the bottom of the Eerste River, to resurface and be made visible? Perhaps it is through the collapse of persisting structures, institutions and attitudes that actual transformation can occur.

The mouth of the Eersterivier near Macassar Waste Water Treatment Works, False Bay

The mouth of the Eersterivier near Macassar Waste Water Treatment Works, False Bay

Athi Mongezeleli Joja, Ghosts, 13’52 min, Ridder Thirst LP Face B

In the form of an essay/lecture, Athi Mongezeleli Joja’s Ghosts turns our attention to the signifying effects of mythological formations of our social worlds. Joja, who is an art critic, turns to the signification of the ghost as a conjuring force in critical race discourse, whose presence, he argues, is marked through its residues and traces. His audio notes respond to the Eerste Rivier, its early colonial histories and the erasure of black bodies under colonial modernity. He states, “without erasure there are no whites”. And correlatively observes how the West simultaneously disavows its own mythological embeddedness. This is not far from what sociologist Rolando Vázquez argues when expanding on the logic of whiteness and colonial modernity. He writes,

[Coloniality] is the negation of many worlds of meaning, and the silencing of other worlds. This silencing is a form of negation of the other. While the west has been producing the other as a negative representation of itself, it has to also negate the other as world reality. What coloniality shows is a double negation by the west: the active silencing and disavowing of the other, while at the same time negating this process of silencing. In other words, when the west speaks or represents the world, it represents itself as a totality, and modernity as a total historical reality. (Vázquez, 40)

Towards the end of his notes, Joja takes an Afropessimistic turn, arguing that it is not enough to insert the black subjects into existing systems. His proposition instead is to“dispossess whiteness of the signifying power and the material elements that sustains its privileges.” Transformation requires not only symbolic change, but material change, epistemologically through knowledge and curricula in school and universities, and through land expropriation. Joja echoes thinkers like Frank B. Wilderson who, in the tradition of Afropessimism, poses a critique to the concept of the human, and the existential and affective structures of being. For Afro-pessimists, the black subject is exiled from the human relation, which is predicated on social recognition, subjecthood, and the valuation of life itself. Following this, black existence is what theorist R.L. refers to as “fundamentally marked by social death, materially living as a sentient object but without a stable or guaranteed social subjectivity.” The concept of social death referred to here was developed by Orlando Patterson, who in his book, Slavery and Social Death: a comparative study (1982), argued the gratuitous violence, dehumanization and enslavement deprived Africans of what we today refer to as basic universal human rights. Put differently, the slave ceased to belong to any social order. What is it then, to have a voice when you are marked by social death, when the conditions under which one lives preclude even bare life? The anti-blackness that persists in the United States and in South Africa continues to condemn black lives, is not left undeterred, but met with resistance and resilience, heard in whispers and shouts.

Rachel Collet, The Flood, 07’23 min, Ridder Thirst LP Face C

Speaking to both historical and contemporary conditions, Ridder Thirst LP is a collection of audio that speaks to cultural and political environments from multiple subjective vantage points in a post-apartheid South Africa. The artists and writers on this album artfully orchestrate a multitude of concerns, imaginings, and responses that attend to the urgencies facing a generation of South African youth. Through the various modes of address on this album, De Swardt acknowledges that it is impossible to speak in one unified voice about any category, whether it be women, LBGTQI, indigenous people and other marginal subjects, unlike the unifying rhetoric of democratic optimism that was figured through the Rainbow nation. The different grains and temperaments of voices we hear reminds one to keep an open ear. De Swardt and his collaborators remind us as listeners to extend the limits with which we listen.

Notes

1. Rosi Braidotti, Language is a Virus. Serpentine Galleries.

URL: https://soundcloud.com/serpentine-uk/rosi-braidotti-language-is-a-virus-1

2. For further reading on ontology within sonic theory and questions of race, see Marie Thompson. 2017. Whiteness and the Ontological Turn in Sound Studies, Parallax, 23:3, 266-282.

References

John Corbett and Terri Kapsalis. Aural Sex: The Female Orgasm in Popular Sound. TDR (1988-), Vol. 40, No. 3, Experimental Sound & Radio (Autumn, 1996), pp. 102-111

Abri De Swardt. Wat Praat Jy! On Contemporary Art and Afrikaans. Adjective, Issue 1, Volume 2, Summer 2018, pp. 36-45.

Frantz Fanon. Black Skin, White Masks. New York. Grove Press, 1967, pp. 17–18

Patrick Feaster. Phonography. In Keywords. (Ed.) David Novak & Matt Sakakeeny. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015, pp. 139- 150.

Douglas Kahn Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999, p.7

R.L. Wanderings of the Slave: Black Life and Social Death. Mute. 5 June 2013

URL: http://www.metamute.org/editorial/articles/wanderings-slave-black-life-and-social-death

Penny Pistorius and Stewart Harris. Heritage Survey: Stellenbosch Rural Areas, June 2004.

URL: www.stellenboschheritage.co.za/wp-content/uploads/099_Konstanz.pdf

Rolando Vázquez, Listening as Critique. In Bhavisha Panchia (Ed.) Buried in the Mix. Memmingen: MEWO Kunsthalle,2017, pp 39-50.

Biographies

Bhavisha Panchia is a curator and researcher of visual and audio culture, currently based in Johannesburg.

Abri de Swardt is an artist and writer based in Johannesburg. He holds a MFA in Fine Art (with distinction) from Goldsmiths, University of London (2014), and is a graduate of Market Photo Workshop and Stellenbosch University, where he received the Timo Smuts Prize. His work concerns injustices of recognition and remembrance in relation to queerness and decoloniality. Across video, photography, sound, sculpture, and performance he engages a self-termed ‘aesthetics of drowning’ and ‘sunstroke of voice’, in which medial super-saturation prompts inhabitations and articulations that situate and unwrite ecologies of body and place.

Stephané E. Conradie is a lecturer in printmaking at Stellenbosch University, where she is a PhD candidate in Visual Arts. Although primarily a trained printmaker, she is known for her bricolage assemblages. Her research focuses on trying to make sense of her social and cultural ‘situatedness’, in a Southern African context. This focus stems from a fascination with how people categorise and arrange objects in their homes, particularly her own family members in both Namibia and South Africa. These objects have provided her with a language to investigate the creolised formations of identity that are linked to South Africa’s histories of colonialism, slavery, segregation and apartheid.

Metode en Tegniek is the collaborative stage name of Rompilus van STADENBERG and Say Hooersquillkeytarkey. Being completely unoriginal, obscure and irrelevant, they foolishly continue to waste money producing music that no one really cares about.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja is an art critic.

Pierre Fouché introduces himself as a lacemaker although his practice incorporates a broad range of media and conceptual approaches. He achieved his MA in Fine Arts from Stellenbosch University in 2006 and has had 8 solo exhibitions since then. Notable recent group exhibitions include Lace/not lace at the Hunterdon Art Museum in Clinton, New Jersey, Women’s work at Iziko South African National Gallery, and the touring exhibition Queer threads first exhibited at the Leslie & Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, New York. His work is represented in the public collections of the Iziko South African National Gallery, and the Artphilein Foundation, Switzerland.

Khanyisile Mbongwa is Chief Curator of the Stellenbosch Triennale. She is a Cape Town-based independent curator, award winning artist and sociologist. She works with public space, interdisciplinary and performative practices, unpacking the socio-political, socio-economic, socio-racial, gender-queer and historical-contemporary complexities and nuances of the everyday. Currently she works with the Norval Foundation as Adjunct Curator for Performative Practices and with Cape Town Carnival as Curatorial and Socio-Critical Development Advisor.

Rachel Collett is a practicing artist and a lecturer in Visual Arts based at Nelson Mandela University. She holds a MA in Visual Arts from Stellenbosch University and is currently working towards an auto-ethnographic practice-based PhD in Visual Art. She is interested in the relationship between self and culture and in the concept of reflexivity. Her recent work uses various combinations of painting, projection, text and voice to reflect on belonging as something that waxes and wanes in strength, a fluid state that is temporary by its nature, and that involves a cost.

Alida Eloff holds a fine art degree from Stellenbosch University. She is currently doing her MA in Creative Writing at the University of Pretoria. She often uses her self-diagnosed agoraphobia as an excuse for doing as little as possible. She is not vegetarian.