Bubbling under the surface of Africa’s urban landscape is a style of art historically viewed as provocative, empowering and intrinsically attached to black culture. The street art scene – in particular from South Africa – is responsible for the vivid murals and art work strewn across its metropolis and suburbs.

Christabel Johanson on Street Art in Africa

Faith47, 2017

The African Street Art Scene

Throughout the decades, the West has embraced black and African art forms. From the BLK Art Movement, the resurgence of tribal art and the rising popularity of artists from Africa, Western society has had an on-going love affair with the creative work from this continent.

However there are some who argue this relationship is exploitative, a mere fad or only for the gain of rich people. Some explain that it is better to place the power of galleries, exhibitions and art back into typically black spaces.

*

Fortunately the tide may be turning. Bubbling under the surface of Africa’s urban landscape is a style of art historically viewed as provocative, empowering and intrinsically attached to black culture. The street art scene – in particular from South Africa – is responsible for the vivid murals and art work strewn across its metropolis and suburbs.

*

In the timeline of street art (classified as graffiti, large wall murals, posters etc.), its existence has been a contentious subject with authorities condemning it as vandalism or a low brow display of creativity. The form was popularised in the late 1960s and 1970s with the emergence of tagging which is a visualised “signature” of the graffiti artist. Artists later developed their style with spray paints on buildings, walls, tube or subway carriages. As they upped the ante, graffiti would be found in higher floors, more dangerous locations and impossible places. Any viable surface became the canvas for this breed of cosmopolitan artist.

*

Despite the danger and disapproval surrounding its reputation, graffiti and similar art forms provided a voice for disempowered groups suffering at the time. In America this included the poorer families and black communities who were not only poorer but socially disenfranchised. It also pushed back against the “greed is good” attitude of the 1980s when advertising and capitalism were rife. Due to its growing link with Hip-Hop and black culture it was easily dismissed as disruptive and brash, but for artists it was the platform to express their anger, dissatisfaction and critique the issues around them. Later hugely famous characters like Jean-Michel Basquiat adopted street art styles as part of his own work amidst the backdrop of trendy New York City. This popularised and raised its profile to a level where art aficionados began to take notice.

*

By the 1980s the momentum of street art had spread across America beyond the bigger cities of New York and Washington, and soon towns and cities had their own offerings and local icons. Barry McGee for example was one of the most famous figures from the time and fused other counter-culture communities like surfers, skateboarders as well as street artists to form a bigger collective and larger audience for his work.

Barry McGeee, Untitled, 2010

Across the pond street art was embraced in the urban forums of Paris, London and around Europe. Within Paris “Blek le Rat” was an artist who used stencils to draw more ornate pieces. Then in England in the late 1990s and early 2000s the Banksy craze hit hard. With his personalised style of dark humour and satirical imagery Banksy politicised street art once again. Staying anonymous made his reputation soar as people guessed the identity of the mysterious artist, and this fascination led to exhibitions and even a documentary. This was another milestone for street art as the fame and value of Banksy’s pieces confirmed to the world that it was here to stay.

Blek le Rat, Rats

In fact the movement has now spanned all corners of the globe and is especially thriving in Africa. In particular South Africa has become a hub of exciting and innovative work in the genre. From the townships, suburbs and everywhere in-between there are hosts of artists that are using the cityscape as a platform to express a vision. The downtown neighbourhoods of Braamfontein and Maboneng are famous for their public art works and activism. Newtown in the old district of Johannesburg is renowned for its graffiti. Being created by artists from diverse backgrounds and different social and political visions, South Africa is becoming a growing monument of innovative work.

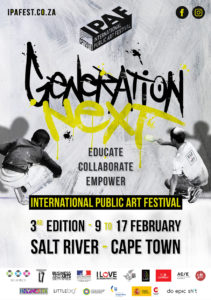

Its popularity has grown so much so that The Cape Town International Public Art Festival has been developed to showcase the variety of fresh and unique talent on offer. It held its third festival in February 2019 which ran for nine days. The mission of the festival is to educate, collaborate and empower. This is a great example of how communities here are embracing and drawing inspiration from public art. The attitude is different from the old fashioned ideas of graffiti and its related forms; here it is being seen as a form of visual media, a collaboration between communities or countries and an important creative dialogue.

*

Here is a spotlight on some artists with a deeper meaning behind their work, who are paving the way for public art in Africa and raising its profile internationally.

*

Sonny Sundancer

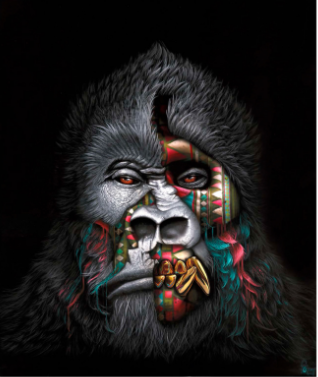

This British-born artist is based in Johannesburg. He has a passionate love of animals and wildlife and to this end his To the Bone collection of murals seeks to raise awareness for endangered species. In his pieces we see animals’ faces fade away to reveal bone, skeleton and tribal print. This highlights their impending danger they face and the tribal patterns reminds us of humanity’s intrinsic responsibility to look after them. The patterns also link back to African heritage and culture.

Sonny Sundancer, Kunga, Hand painted canvas, 1200 x 1000mm

The Bushman

The Bushman is a Cape Town native whose work focuses on influencing audiences for the better; his art work encourages real life encounters and interactions rather than living life online. He often uses bright colors and quirky imagery to catch the eye and has been hosted by The Cape Town International Public Art Festival in the past.

The Bushman, Good Vibes Only, 2017-02/2019-02

With Good Vibes Only the bright colors and jaunty font serves as reminder to look on the positive side of life. Set against the barbed wire backdrop this works to uplift the surrounding area; giving hope and optimism to an otherwise daunting setting.

Ricky Lee Gordon

Ricky Lee Gordon was born in Johannesburg in 1984 and now works primarily in Cape Town. His pieces are displayed on large murals not only in Cape Town but Kathmandu and Istanbul. The artist previously worked under the pseudonym of Freddy Sam but now uses his real name, and in 2013 he made the swap between spray cans to brush which helped developed his large-scale murals. His website states that “his paintings explore the nature of non-duality and interconnectedness focusing on bringing to light relevant social issues.” His mission with the murals is to epitomise the community it represents; something identifiable and inspirational. In Ricky’s own words “I am trying to create beauty in my work that allows for beauty in other people.” One of his signature murals is I Am You, You Are Me, residing in Cape Town.

Ricky Lee Gordon, I Am You, You Are Me, 2016

Being inspired by Buddhism and meditation, Ricky’s portrait uses blacks and whites to tell a poignant story. I Am You, You Are Me echoes Buddhist teachings of interconnectedness. The black figurehead reminds locals perhaps of the apartheid and the segregation people experienced, when really we are all humans and therefore connected in oneness.

*

Falko One

In 1988 Falko One began painting high school walls before the apartheid was set in. He was inspired by the Hip Hop scene at the time and groups like the NWA influenced his work. His paintings are fluid and dynamic and many of his murals can be traced throughout Cape Town down the sides of homes and buildings. Being a veteran of street art, Falko One is now considered one of the most important urban painters of the scene. As his favourite subject the elephant becomes a symbol of Africa and in the below example is adorned in the same tribal patterns as the women. Again this highlights Africa’s bright and long-standing heritage as well as strengthens the link with black identity.

Falko One, (Luke Daniel/Red Bull Content Pool)

What is more encouraging is that this phenomena is spreading across Africa. The continent is booming with galleries and exhibitions which only prove that the art is evolving and its audience is growing. Nairobi is springing up more street artists, Senegal boasts its first female graffiti artist Dieynaba, and Morocco has the Jidar street art festival which hosts local and international talent.

Africans are embracing their own creative identity through the multitude of projects – there is no denying the character and beauty African art has bestowed onto the world. However it is now time to embrace its independence from Western spaces and appreciate it on home ground.

*

Taking back this space and in fact adorning the exterior spaces of Africa evokes the same rebellious, innovative and energetic spirit of the early public artists looking to send their message out to society. Making a spectacle of their territories through paintings, graffiti, posters and so forth is the most effective promotion African art can make. By daring to work outside of the sanitised world of curated spaces there is a solidarity and unified message that seeks to be free and find their own voice once more.