I feel it as one of the important tasks of a social engaged artist like myself and other artists, activists and cultural innovators to subvert and change the culture we find ourselves in. We are in a cultural war and, to echo Gordon Parks, the camera is our weapon of choice.

Rob Perrée interviews Ajamu.

Julius Ruben, from the Fierce Series, 2013.

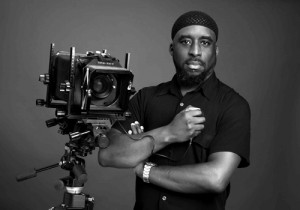

AJAMU, QUEER PHOTOGRAPHER AND ACTIVIST

The first time I met Ajamu was more than 20 years ago at a book launch in a gay bar in Manhattan. His first body of work was published in an attractive, square little book. The second time was a week ago in a church in Brooklyn. A former church, I have to say. The religious building was turned into an apartment and studio complex. The gay bar is by now sold to a commercial developer of the lower West Side. Luxurious apartments have turned a popular gay bar into history.

Ajamu is born in Huddersfield, England, and lives and works in London. He is a photographer, curator and activist. He is founder of the rukus! Federation (2000). In their own words: “rukus! Federation is known for its long-standing and successful program of community-based work with Black Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual, Trans artists, activists and cultural producers nationally and internationally. Our work has a reputation for being dynamic and participative, and includes one off events, screenings, workshops, theatre performances, club based events, debates and exhibitions. “rukus! has a big queer archive and exchanges information and material with other specialized archives. The archive of the Schomburg Center in Harlem, among others.

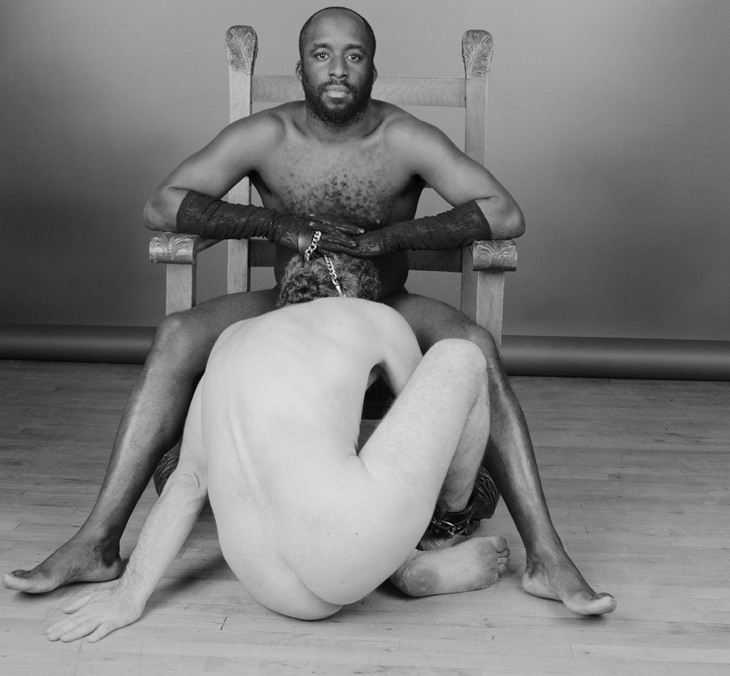

From Circusmaster Series, 1997.

From Circusmaster Series, 1997.

Ajamu puts his work in a long tradition of socially engaged photography, but there is a big difference. In the past the medium was often used as a way to classify people. His work is more about archiving black and queer people, as a way of giving them a place in history. He is aware of the fact that there is a difference between how people are generally represented and how they are, in particular marginalized groups like queer and black people. His work can be seen as a correction of that ‘image’. He is also very much aware of the fact that the context in which people see photos has a great influence on how these pictures are read. As being objectified as a black queer photographer influences the way his photos are read too.

Ajamu’s work is presented in galleries and museums in many cities and countries (New York, Berlin, Amsterdam, Senegal, to name a few). He is in New York now as a curator-in-residence preparing a big project for next year. In the meantime he makes portraits of a diverse group of ‘sitters’.

The interview started as an email dialogue, but when we realized that we would be in New York at the same time we decided to give it a live following.

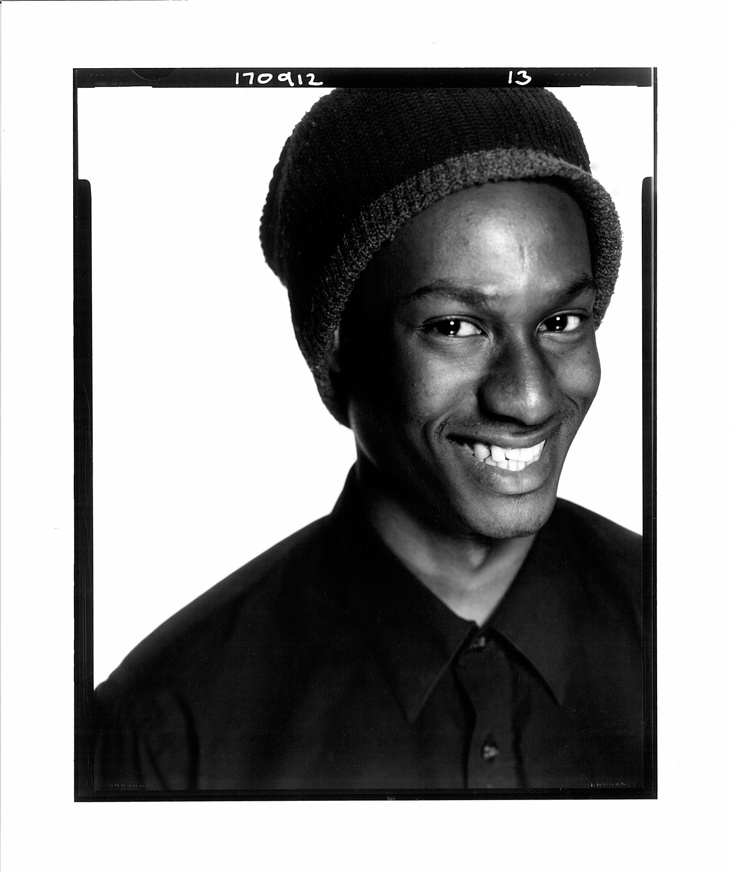

Self Portrait..

Rob

Why do you use photography as a medium?

Ajamu

My earliest recollections of photography were dressed up in our Sunday best with my brothers and sister for our family photo. I cannot remember what camera was used, given it was the late 60’s it would more likely be a MPP press camera or a Crown Graphic field camera. However it was the anticipation of waiting for the prints to come back and this paper called a photograph always intrigued me. In my early 20’s I was setting up an independent black magazine called ‘blac’ and needed a photograph to accompany an article I was writing. I borrowed a camera, took the image and fell in love with the medium. I used to photograph the guys in town I was attracted to in my makeshift studio without them being aware of my sexuality. I also came across African –American pornography from the private sex shops. While they affirmed my desires, I found them problematic in their representation of black men. In a vague kind of way I knew I wanted to capture some of that energy, tension and sexual frankness in my own work. Photography is my visual voice and the medium I feel the most comfortable in expressing my self in.

Rob

Why analogue photography?

Ajamu

I am drawn to analogue as I have a love for the early 19th century photography, in particular the Pictorialist movement, and for the traditional printing processes specifically Platinum/Palladium prints. Working with large formats, either 5 x4 or 10 x 8, is cumbersome. The camera design has not changed that much in over 150 years. What I love about analogue is that there is always an element of chance and risk, as you never know what you have on the film until you come back from the printers. Since most of the process involved from loading the film by hand to printing, there is a level of intimacy involved. Large format photography including photochemical processes keeps me connected to the material and textural nature of the medium. Because of the social media we are surrounded by an endless amount of digital images. I am not in competition with these images. I like the craft of the medium. I like the process, the nostalgia that goes with it. And, I am wondering if all these digital images are really seen. There is more to the medium than look and delete.

Rob

Why mainly black and white?

Ajamu

Black and White for me is not devoid of color. As I like working with various tones, mainly I work with mid grays. I always see different graduation of blacks, whites and grays. It also reflects my politics generally. It is never black and white but has shades and nuances of grays. Black and white always brings in notions of nostalgia, a history, and a past as it alludes to a particular tradition of the medium.

Rob

But ‘activist’ and ‘gray’ do not sound like a match to me.

Ajamu

For me there is no fixed line between a photographer and activist. A photographer is an activist, as there is no clear line between an artist and a curator or between an academic and an artist. Politics are complex. It is never either or. It is more nuanced. It is more like gray.

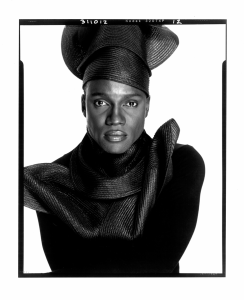

Hakeem Kazeem, From Fierce Series, 2013.

Rob

How do you position yourself, as a fine art photographer or as a commercial photographer?

Ajamu

I position my self as a practice led fine art photographer as I am also interested in ideas of aesthetics and notions of beauty. This could be from the lighting style I am using and exploring, the scale of the print, the matting, the style of framing, how the work will look on the gallery walls, will I work with white walls or subvert the white cube …all these are part of the creative process and just as important as well as the social, cultural and political issues I explore within my practice.

Rob

How do you pick your models, or sitters, as you call them?

Ajamu

Sitters are chosen depending on the kind of project or body of work I am working on. For my most recent exhibitions, which are portraits – ‘Through a Queer Lens: Portraits of Jewish LGBTQ people’ presented at the Jewish Museum London (2016) and ‘Fierce: Portraits of Black LGBT people’ at the Guildhall Art Gallery (2013) – the sitters were selected on the basis that they were mainly artists, activists and cultural producers. ‘Fierce’ was more specific as the sitters were mainly under the age of 35, whom I have referred to as a second generation of predominantly Black British born. This body of work was me celebrating a group of sitters I am inspired by and in part to foster a cross-generational dialogue between them and myself. In my early work, most of the sitters, if not all were either lovers, ex-lovers or fuck buddies and in some cases one night stands who also allowed me to photograph them in the early hours of the morning after a fuck session.

Rob

Does there have to be some kind of intimacy between you and the sitter?

Ajamu

Intimacy sexual and/or non- sexual between my self and the sitter has to be there for the image to work. It’s like stealing a kiss: it’s the thing that happens between us. Sometimes my strongest images are with someone who is a total stranger. If I am shooting commercial work I may only have 15 minutes to make contact, get the image. From the moment the sitter enters my studio I am observing every move. I want to have a deep sense of connection. Once they sit down and I look through my viewfinder I can sense whether we are connecting or not.

Rob

You try to involve the sitter in the way you portray him or her. Why is that so important for you?

Ajamu

Once again, this all depends on the kind of work I am shooting. Images have a life of their own, and photographs can be read differently depending on the time and context and who is reading the image. So for me when the sitter is involved in that process, sometimes what they do is give you a gift image, which is an image that I did not expect. If I am able to capture a sitter laughing for instance, I know that that the image is a sign of they trust me.

Nice Rass, 1993.

Rob

Are there commissions you refuse to do? Do you have your (moral) limits?

Ajamu

Only if it is about politics I don’t agree with. There has to a connection. I have to feel good about it, otherwise it is impossible to make good work.

Rob

No portrait of Donald Trump.

Ajamu

No, no portrait of Trump. Only if he is gagged so as to stop him exposing such bile.

Rob

Is your work about identity?

Ajamu

Identity is one of the themes in my work, however I would say it is primarily about difference and how we celebrate and/or negotiate these differences within neo liberal societies. I think because I am author of my work and appear in my work, or the work does explore the usuals (race, gender, sexuality) I think there is cultural shorthand to think that black and queer artists’ work can only be about identity and representation. My concern is that this blind spot is a way to sidestep the nuances in our work and practice. What I am most interested in is how we can move outside of the straight jacket of identity politics. Pleasure, the erotic, the sensual in key to my practice. I am thinking about one of my favorite quotes by Foucault: “What we must work on, it seems to me, is not so much to liberate our desires, but to make ourselves infinitely more susceptible to pleasure”. That said identity and representation have a way of always creeping back into the work even if you are trying to avoid it.

Rob

Does your work create the possibility for gays to identify because you did not have that possibility growing up.?

Ajamu

My work is has always been about subverting the notion that there is a homogeneous gay gaze. Growing up the images of gay men, predominantly white, where problematic in mainstream and popular culture, images of black men were equally problematic, as black men were framed within a narrative of fear, threat, desire, fascination and as someone who identifies as both my work has always been not just about playing with and against these concept-poor notions of identity. The experiential and bodily experiences are key for me as someone who found the templates of what it meant to be gay, black, black and gay limiting. I am far more interested in the more nuanced dimensions of my otherness.

Rob

Is a portrait for you always about the person you portray – his personality, his gender, his fetish, his character – or are formal aspects sometimes more important?

Ajamu

The portrait whether I am photographing someone who identifies as male, female or gender non-specific may include some of the above, but equally it is about what I also want to project on to the sitter. It is pleasurable crafting photographs. I get excited by when a sitter highlights his facial or bodily flaws, more often than not, that is what I find most attractive about the person.

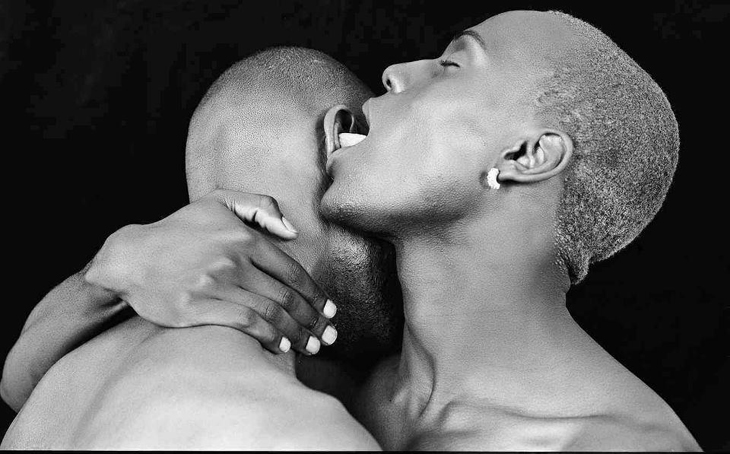

The Kiss, 2000.

Rob

How important is the erotic element in your work?

Ajumu

The erotic and the sensual are at the core of my work and everything else is connected to that and branches off from that. Going for pleasure is not in contrast with activism. Pleasure is political Again, I see these things and feel these things outside of an either or paradigm but a both/and paradigm.

Rob

Are you in your work or the interested observer? Mapplethorpe slept with his ‘models’; Nan Goldin lived with them…… etc.

Ajamu

I am in my work and the observer. I am in my work and simultaneously not in the work. This also depends of where people draw the line (which I think it can’t be drawn) between the artist and what is being produced. For me in regards to my practice it has never been a case of either or, it’s always been a case of both AND.

Rob

Some of your works have a tragic undertone – the Circus Master series for instance – others are more detached. Is there a reason?

Ajamu

Personally I think that having tragic undertones in an image is not necessary negative as I think photographs should elicit an array of competing affect/effect simultaneously. The ‘Circus Master Series’ came out of a body of work called ‘Anti-Bodies: A Spectacle of Strangeness’ which was commissioned by Autograph –The Black Photographers Association. I have spent 4 weeks in the Light Work community darkroom with the Ron-G. Becker collection, which consists of 19th Century ‘cartes de visite’ of 19th century circus freaks and side-show performers.

I was interested in Freak Shows, as I wanted to make the claim that despite the advances of feminism and queer politics, culture increasingly fetishes and adores the body beautiful and sidelines non-normative bodies. The terminology freak and aspects of the circus for me are an ideal metaphor for those of us who feel dislocated, estranged, alienated and marginalized within contemporary culture and including our own black and queer communities.

Selfportrait with Mike, Syracuse, 1997.

Rob

Some people call your work fierce, others freaky or provocative. How do you react on these qualifications?

Ajamu

I do not react to these qualifications, though I am aware how the work can be read through these lenses. When you grow up in an erotophobic society and you create work that moves away from a shame based identity or oppression based narrative and celebrates the dirt, grit and messiness it can only be seen as provocative. As a child I have always been mischievous by nature and still have those traits. In relation to my art I see my practice as ‘playful yet serious’ or even softly subversive. However I believe that once the work has left the studio and is presented in the public domain, whether in a museum, a gallery or a publication, it is all up for grabs and it is no longer my work as such, as the viewer /spectator will always bring his, her viewpoints and in some cases see what they want to see.

Dorethea Smarte, Writer Spoken Word (above), Zami Series, 2007-2008.

Vima Lasara Mason-John, AKA Queenie, Writer, Zami Series, 2007-2008.

Rob

Can you tell more about the people who influenced you?

Ajamu

There is no one artist my work is influenced by or in reaction to. However I acknowledge that not all influences are conscious. There are photographers, artists, writer, musicians and philosophers I always come back to. I am also loathed to create some kind of hierarchy, as my work is concerned with subverting hierarchies. However for the purpose of this interview, and I am sure I will forget many artists, I could mention Joel Peter Witkin, Diane Arbus, Pierre Moliner, George Dureau, Claude Cahun, Rotimi-Fani-Kayode. Writers De-Sade, Georges Bataille, Stuart Hall, Michel Foucault, Johnny Golding. Black and white movies like such as Freaks, The Cabinet of Dr Galigari, Elephant Man, Whicker Man, Night Porter, Looking for Langston.

There is also a group of artist/photographers I am silent fans and follow their practice as much as possible Zanele Muholi, Omar Victor Diop, Shikeith Nieree and Rodel Warner

Rob

You have a mission. Your community is important for you. Like it is important for photographers like Zanele Muholi. Is standing up for your community part of your work or a kind of side-effect of your work?

Ajamu

As a fine art photographer, archivist and activist, as someone born and raised with and in the UK and of a particular social milieu, my work is about creating an unapologetic counter narrative to how our lived experiences have been silenced, sidestepped within the black and wider gay community’s social and cultural history and within the national narrative.

As long as we continue to experience, racism, homophobia, transphobia, heterosexism on a quotidian and systemic level, as long as our experiences are framed within an oppression-based narrative then my work by developing a celebratory and aspirational framework needs to be created. This is not to say that this is the only lens I look through or create from, but I feel it as one of the important tasks of a social engaged artist like my self and other artists, activists and cultural innovators to subvert and change the culture we find ourselves in. We are in a cultural war and, to echo Gordon Parks, the camera is our weapon of choice.

Rob

On Facebook you position yourself as a promoter of photography. Do you take that role out of necessity or out of love for the medium? You are self-taught. Do you promote that too?

Ajamu

I am auto-didactic to a large extent and generally drawn to artists and practitioners who are auto-didact too. Many moons ago I did start a photographic course but found my self in constant tension with the lecturers on what photography is and should be able to do. I was also studying a Black History course at the same time, and felt photography should be used for social and cultural change. It’s interesting that a decade later I am coming back to those early 19th century photographers and the early stages of the mediums development.

I do not believe that a professional education as in being aliened with an institution is the only way for artists to learn their craft or navigate their way in the art world. In fact I would argue that some intuitions are detrimental to some artist’s creativity. I know that there are some intuitions where if we come back to questions of identity and creative practice black and queer artists work is rarely taught. I would go as far as to say that in the Black British – including Queer Black British – experiences, creativity is largely unexplored and underdeveloped within art schools and academia.

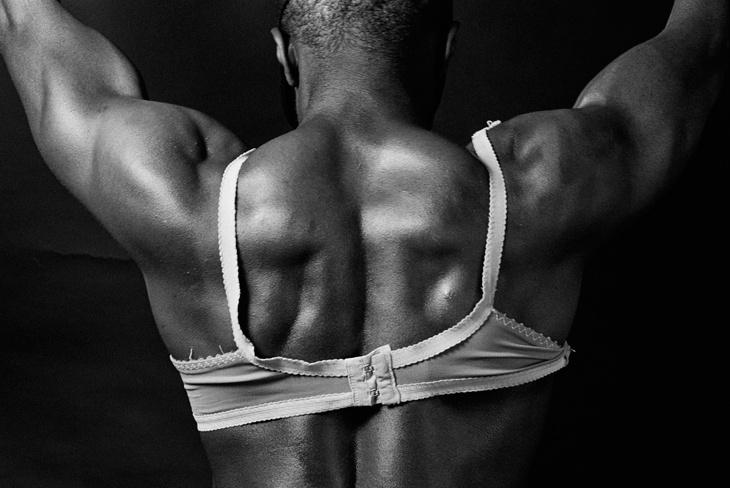

Bodybuilder with Bra, 1990.

Rob

This photo was my introduction to your work, more than 20 years ago. I told you about me being present at your book launch in NY. In what way is your present work different from that body of work?

Ajamu

My last two bodies of work have been more focused on portraiture. Portraits have always been part of my practice, but they were never fully realized as bodies of work. And…..the last few years I have worked more on collaborations. For instance my current project ‘I Am For You Can Enjoy’ is collaboration with Khalil West, a curator with the Homotopia festival and founder of Chew Disco. Our project includes portraits and filmed testimonies of black queer sex workers.

Some of the themes I have always been interested in are still there. Like black and queer experiences on the margins of black, the wider LGBTQ experiences and narratives, celebrating black queer agency, those experiences that we don’t want to talk about like pleasure, taboo and transgression. In general I think that an artist should be able to explore whatever he wants. You can’t expect him to stick to his original work. Even if the viewer prefers that kind of work. It is wonderful that Muholi’s last body of work is different from her community based work. You cannot make the same kind of work all the time.

Rob

Do you have a new project in mind?

Ajamu

I am going to make a series of photos of sex objects for an exhibition which will open in 2017. In my early work there were more often objects, but always combined with people. It is not such a big step. There is always a kind of intimacy around sex objects. And pleasure. They are related to people. You feel the connection with people. They are there without being there. The viewer will project his/her/Zir fantasy on them. Even identification is possible, like in my other work.

Rob

But the element of representation will be gone.

Ajamu

Yes, yes, that is true.