I should say something about the style of Mawimbi’s drawings. These are often described as minimal, but that is a confusing term especially in an art-critical context. These drawings are pregnant of signs and symbols. I would call them classical, in the sense of ancient Greek classicism, like red or black figure vase painting in which contour is also used as the restrained mode of expressive figuration. Such a style was of course familiar from (sculptural) images in pharaonic – that is African – antiquity. Mawimbi’s drawing has a strong affinity with the contemporary application of this style, namely playful comic.

Jelle Bouwhuis on the drawings of the Kenyan artist Alex Mawimbi

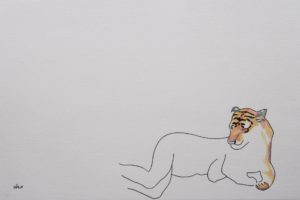

Untitled, 2016

Alex Mawimbi

Displaced Artist Formerly Known As…

I stumbled upon the solo exhibition ‘Self-Referential’ by a certain Alex Mawimbi at Sanaa Gallery in Utrecht, and I got confused. Not because it is a subdued exhibition. It consists mostly of two-dimensional work: four series of framed drawings, a set of prints and a couple of (older) video works on screens. Two tiny ceramic objects are the only sculptural contribution. No, it was the fact that the work seemed quite familiar to me whereas the artist’s name was not. Most works even carry the signature of someone else. Luckily, the creator herself was there to explain that she is The Artist Formerly Known As Ato Malinda. That former name more and more came to stand for the memory of her abusive father and family. After the recent death of her mother-in-law, and as a therapeutic gesture, she decided to bear that name no longer. Alex on the other hand is just as nice a name, she explains, and Mawimbi is the Swahili word for waves – a reference to the Indian Ocean that borders Kenya, the country on her ID.

In the show in Utrecht Mawimbi presents a score of concept pages of a graphic novel, a kind of a diary in which she reflects on violence, abuse, queerness and her youth – it is planned to be finished over a fellowship at Iwalewahaus in Bayreuth and to be published next year.

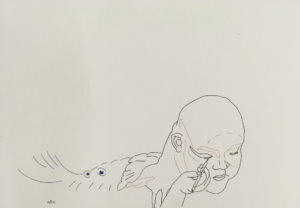

Endangered Species, 2018/Untitled, 2016

Like Ato before, Alex dwells in the realm of African Art. That is to say, we know that there are artists who are ‘from Africa’. There is also a vast infrastructure of institutions that specialize in ‘African Art’. And more often than not, artists from Africa are condemned to dwell within that infrastructure, because it gives opportunities. But epistemically speaking, African Art is a highly undefined and unspecified term. As already convincingly argued by the Congolese-U.S. scholar Valentin-Yves Mudimbe decades ago, the idea of an African culture is a Eurocentric concept haunted by colonial thought. It is carried on in museums that ‘do’ African art even though their presence beholds qualities of synecdoche – objects become representational for the culture of a continent. Although such representation is practically impossible, it is also the reality that artists and audiences have to deal with whether they like it or not (and this predicament is of course not limited to African Art only!).

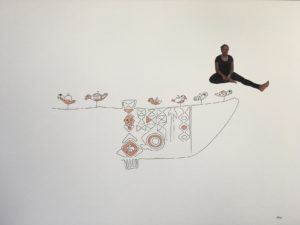

Untitled with Mask by Nuna Peoples, Burkina Faso, 2017

Anyway, Mawimbi thrives on a love-hate relationship with it. In interviews with her (1, 2) and in descriptions of her work, we encounter the marker ‘Africa’ as unavoidable feature that everything presented is infused with. Yet if we just take the drawings in this exhibition by themselves, without all this contextual information, it is actually absent. There is only one series in which that Africa marker is used, through the incorporation of depictions of African sculptures from the collection of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington. Each sheet depicts a different sculpture that is accompanied by a depiction of a Barbie doll as well as a collaged black-and-white photograph of the artist herself. This constellation was inspired by the fact that in older textbooks such African fetish or fertility sculptures were described as dolls, hence suggestive of childish emotional ownership, and belittling the actual status of the sculptures and the often violent, colonialist pedigree of African Art collections. In these compositions Mawimbi positions herself as powerless intermediary, or collaborator, unable to act against this epistemic and emotional whitewashing of the objects’ function in living culture.

Mawimbi would love to look for itineraries of queerness and non-binary queer theory in such collections. Especially in places where the idea of an African Art collection is replicated on the continent itself. Unfortunately, Nairobi is not a safe place for her anymore and over the past four years or so she has hardly been back. Although she’s said to be based in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, Mawimbi now actually resides in Hull, a harbor city in North-Eastern England, where the majority has voted Leave. A place that lacks a multicultural queer scene, unlike Rotterdam – or Singapore, the city state that inspired her to make drawings that are also present in her solo show in Utrecht.

Untitled, 2016

I should say something about the style of Mawimbi’s drawings. These are often described as minimal, but that is a confusing term especially in an art-critical context. These drawings are pregnant of signs and symbols. I would call them classical, in the sense of ancient Greek classicism, like red or black figure vase painting in which contour is also used as the restrained mode of expressive figuration. Such a style was of course familiar from (sculptural) images in pharaonic – that is African – antiquity. Mawimbi’s drawing has a strong affinity with the contemporary application of this style, namely playful comic. It is a matter of writing and depicting, reading and seeing at once –like the concept of her upcoming autobiographical book in which letters are prioritized over pictures. The playfulness becomes more evident in a series in which she has depicted herself as a goat (a pun on her previous first name) in an intimate relationship with another goat – each of these couples symbolize important female relationships in her life.

It is hard to relate such gentle and ‘queer’ drawings with Mawimbi’s more militant stances in other works, notably the caged performances she did before in Nairobi and Brussels, or the harsh observations in her upcoming publication. The one theme brings a different vibe than the other and this shows; what can be explained as distraction or lack of focus can equally be regarded as the split expressions of a Displaced Artist Formerly Known As. In Utrecht, the text of a reading performance that she performed at the opening, stands out in Malinda/Mawimbi’s brilliance; both in sharpness and gentleness, Africaness and globalization, in the intangible qualities of each of these and the queerness of life. It tells a story of the artist negotiating the purchase of a wood-carved giraffe sculpture on the market in Nairobi, cutting it into pieces and turning it into an art installation, getting back to the market seller only to tell him that she has destroyed his work. When he asks why, she drily replies: you got your money, didn’t you?

The work can be seen at SANAA Gallery, Utrecht, Netherlands, until February 23, 2019

Jelle Bouwhuis is curator, art critic and cultural entrepreneur. He pursues a PhD research on Modern Art Museums in the Perspective of Globalisation.He is based in Amsterdam.

Notes:

1 + 2

Ato Malinda on sexuality, African feminism and performance as art – interview

An Artist’s Perspective on Africa at the Armory: An Interview with Ato Malinda