Part of my family history is about deportation, we were taken from our land and brought to a new one that we built; we created new cultures.

I like to talk about this topic and others such as immigration and institutional discrimination in my work because they affected my family and ancestors

Alexis Peskine interviewed by Raquel Villar-Pérez

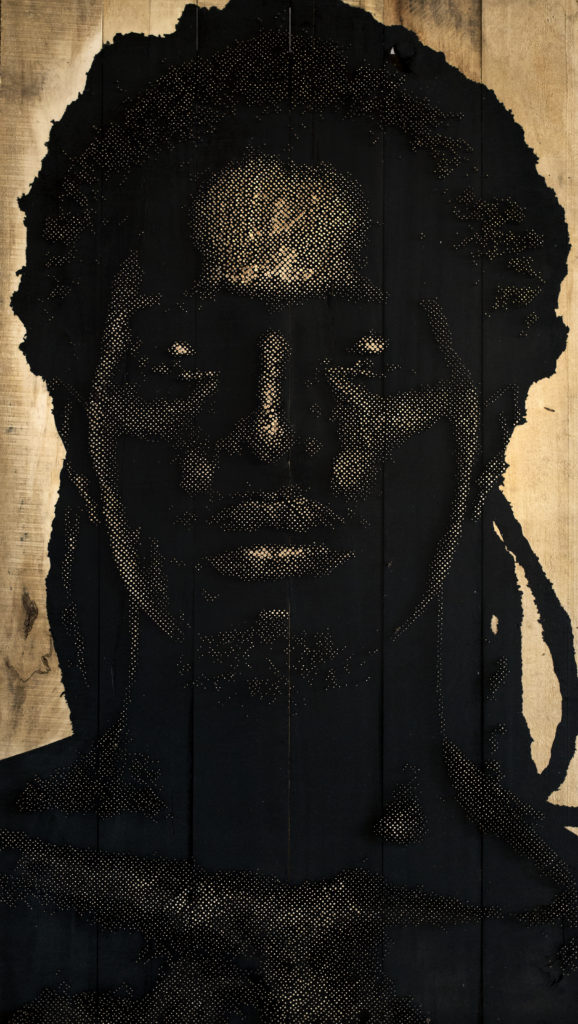

Power, 2017. Moon gold leaf on nails, earth, coffee, water and acrylic on wood, 195 x 250 cm. Image: Alexis Peskine. Courtesy: October Gallery

Alexis Peskine: Power Figures

Alexis Peskine is a visual artist based in Paris. Being born of an Afro-Brazilian mother from Bahia, where Black population is kept off the power by a carefully designed hierarchical system, and of a Franco-Russian father, son of a Jewish refugee who went on exile from Russian prosecution during the Second World War, the artist has been exposed to notions of identity and race from an early age. The trauma that results from daily events of dismissal and rejection lived by the different Others nourishes his art practice. Departing from personal stories, Peskine’s artwork contributes towards the reflection of the multi-layered Black experience particularly in France. Moving beyond the themes of race and identity, his work touches upon notions of migration and inequality, but also sexual, ethnic, nationalistic and religious presumed normativities.

*

His highly acclaimed work The Raft of Medusa at the past Dak’art biennale in 2016, gave him the impulse to further develop in his work notions of migration, deportation and the African Diaspora in the contemporary world. Power Figures, a project in which the artist has been working for the past four months, is the title of his newest series of art works.

His big wooden surfaces encompass sharp, bold, stencil-like images of Black subjects, onto which Alexis hammers nails of different sizes and heights, adding a third dimension to the flat surface. The artist blends together digital arts and primary elements, art and crafts, modernity or neo-Pop and aesthetics of the so-called African tradition, and more particularly of the Nkisi figures from Congo.

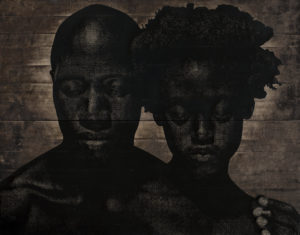

Shrine, 2016. Nails, moon gold leaf, mud, paint and varnish on samba wood, 250 x 250 x 50cm. Image: Alexis Peskine. Courtesy: October Gallery

Alexis Peskine: Part of my family history is about deportation, we were taken from our land and brought to a new one that we built; we created new cultures.

I like to talk about this topic and others such as immigration and institutional discrimination in my work because they affected my family and ancestors. I am amazed about our historical resistance and our transcendence and how do we transform anguish into beauty, into culture.

In earlier works, I would use icons and referential images to talk on a humorous way of identity dynamics, but at some point I felt I had to convey my anger and frustration, so my work became more tormented, in a way is more spiritual and powerful. It has turned into a manifestation of our greatness, of our existence, the people who struggle today.

Soninké Whispers, 2017. Nails, moon gold leaf, paint and satin varnish on wood panels. 241 x 247 cm. Photo Jonathan Greet. Courtesy October Gallery

Raquel Villar-Pérez: Your works seem to function as celebratory redemptions of Black/diasporic subjects. Who are the power figures in your works paying tribute to?

AP: Power Figures are not specific subjects, they represent millions of people, millions of stories, different stories, beauty, resistance, ingenuity, creativity, anger, frustration, power, protection, and ancestry, the ancestors that protect me and protect us. They also represent history and struggle in our world, friction, and aspirations for something better, but also tiredness, being tired of the world’s current state of affairs. It is a departure; it is like an escape and at the same time an affirmation.

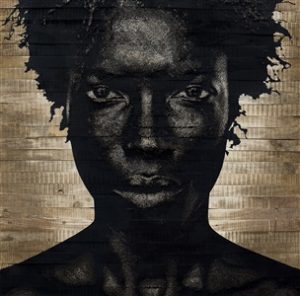

Mandjacko Souls, 2017. Nails, gold leaf and tint on wood, 132 x 93 x 15 cm. Image: Alexis Peskine. Courtesy: October Gallery

RVP: The title of your works, refer to peoples in the African continent: Boy Dakar, Mandjacko Souls, Shrine, Soninké Whispers, and Wolof Cosmic for instance. How do they inspire your work?

AP: I came ‘spiritually’ to the Sub-Saharan Africa in 2010. The first country I visited was Senegal. Ever since then, I gone back many times to explore and travel around. I have been in about fourteen countries so far.

Not long ago I went with a friend who took me with her to visit her family who are Mandjacko people from West Africa. That was her first time going back to her family’s village, and I was able to go with her. In there, I had several mystical experiences: I went to the sacred woods, before that, I attended a ceremony with Djola people; I also went to see a ceremony in a village in Guinea Bissau in the sacred woods. Mandjacko is a tribe and in their language, mandjacko means ‘talk’ or ‘speak up’, and the ceremony is when you go to a little part of the sacred woods and you speak to and communicate with the ancestors. I was welcome to do that and talk to my friend’s ancestors. That was a very interesting experience. In a way, Mandjacko Souls is a synthesis of that experience but not limited only to that experience; it also speaks about being trusted and accepted by my friend’s family who facilitated for me to enter in to the woods and have the spiritual experience.

In that same trip across Guinea Bissau, I also went to a fort, one of the oldest forts where Africans had been captured, enslaved and deported. They have built a museum now. When I went in there, I had visions of conflicts and wars amongst people. I am very fascinated about learning pieces of history of that dark period, of those dark ages. I am particularly interested in the resistance part that is definitely hidden, and many times purposely.

I generally don’t have preconceived ideas when developing a project or new idea. I look at things, I see, experiment, learn; I’m just curious. I have the feeling that part of our history has been hidden. It is like if we have been stripped of some strong part of our identity and our pride. So I am used to do the searching.

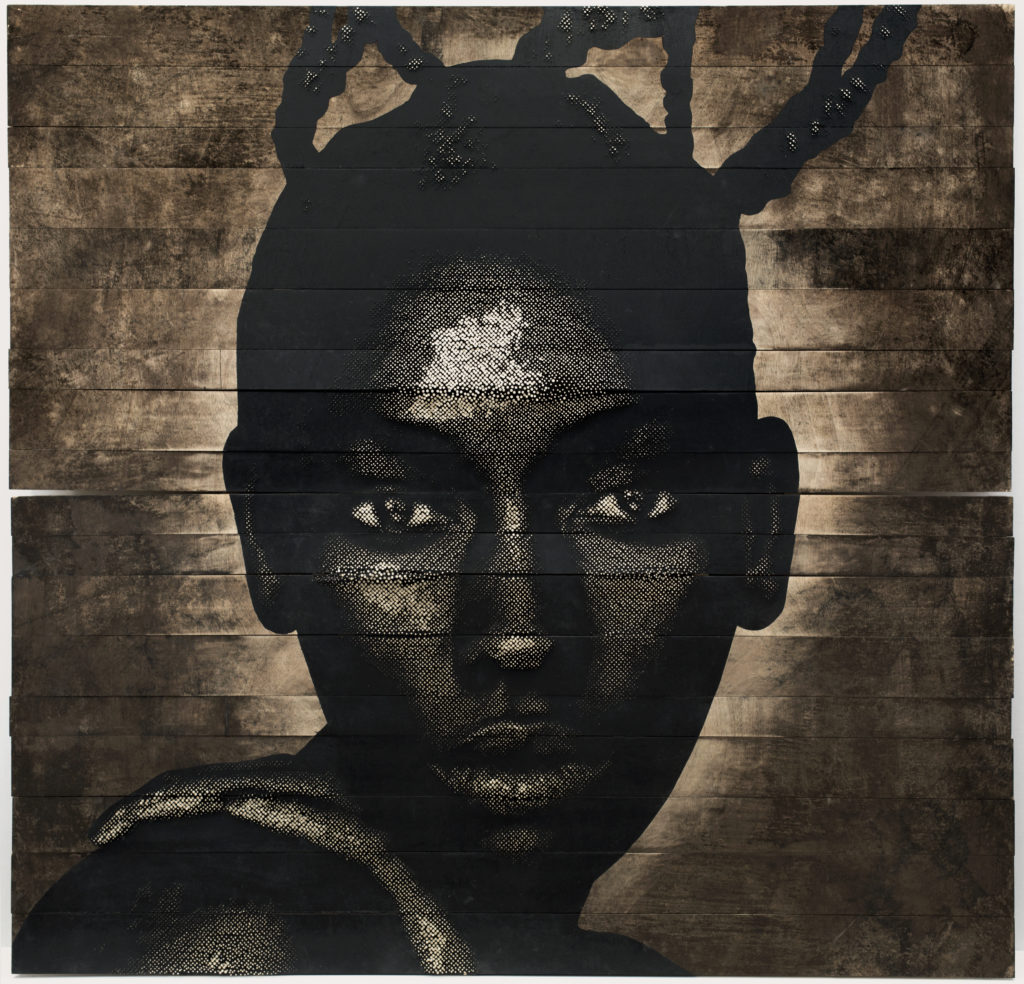

Wolof Cosmic, 2017. Nails, moon gold leaf, paint and satin varnish on wood panels, 250 x 250 cm. Image: Alexis Peskine. Courtesy: October Gallery

RVP: Can you talk more about your visual language?

AP: I use nails on wood. I use gold leaf on top of the nails. I use oxidised Japanese silver leaf, coffee, mud and water for the backgrounds. I use paint, black paint. Tape to do stencils. The silhouettes are very well cut out. The lights on those black bodies and faces are shaped by the different size of the nails and the gold; it comes out of that dark silhouette, the darkness, the faces formed by the light.

I have been working with this visual idiom for about 14years, since 2004. I am keen of simple, strong, bold images. Very straightforward, simple and very balance visually. But I do appreciate more chaotic artists when they, despite that, there is some balanced. I really admire Basquiat.

*

RVP: There is an evident aggressive reading on the use of nails of different sizes and depths over the rendered images. It can be interpreted either as healing acupuncture or voodoo. What is the symbolism behind your visual idiom?

AP: My work is inspired by the Nkisi Nkondi, these are fetishes in Congolese older tradition. They were made to protect their owners from bad eye, bad will by others, and, in a way they empower their owner. They are wooden sculptures with a whole bunch of nails put into it; there would also be a mirror in the belly and inside the belly herbs and other things. All that would aim to protect the person. This is empowering.

When you think of the Black experience on Earth, if you think of Black people of African descent, we need those spirits to protect us; we need power, because we are constantly stripped of our power. Even in a place that is a Black hub such as the United States there is still so much struggle.

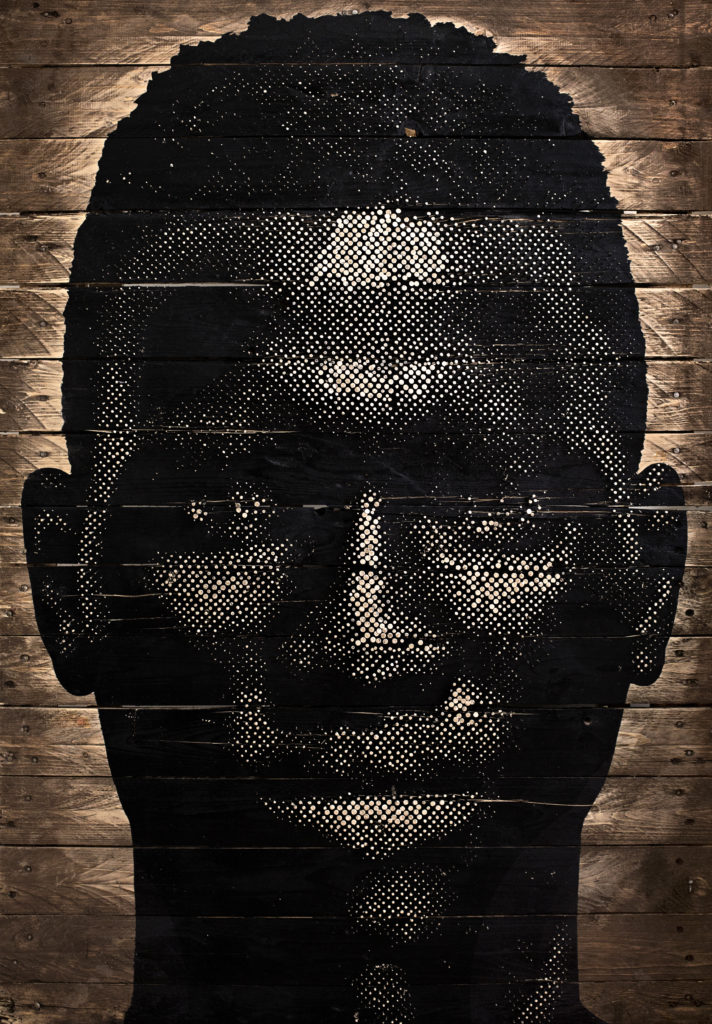

Untitled, 2017. Moon gold leaf on nails, earth, coffee water and acrylic on wood, 240 x 250 cm. Courtesy: October Gallery

Voodoo comes from the Yoruba people, from the region of Dahomey that is now Benin region in Nigeria. When people think of nails and voodoo they think of people putting things in bodies to harm someone; there is no much accuracy on that. In the Western culture, missionaries and people that use to preach the word of Jesus have dismissed the spiritualities of Africans; there has been an effort to vilify and to make those religions look evil.

You can also think of the idea of crucifixion, as in Christian religion, the idea of resurrection and transcendence. So in that sense, nails have a healing and liberating purpose.

In itself, it is an aggressive process; I am using a hammer, gravity, and a little bit of strength to push something called the nail into a living material. As it goes in, if you look at the back of the piece, it tears the screaming wood. In a way, it is creating something, building out of a destructive gesture.

*

RVP: Do you think there is an end to this project?

AP: There will be. I don’t know when it will be. Actually, right now I don’t think of the end; I am thinking of the development. This exhibition is only the beginning. And I need to do more and more images. I definitely want to do big pieces in the next couple of years. I am thinking of places to travel to nurture the project; I want to do video; definitely music and video will be involved. But for the power figures idiom, right now I’m speaking it. And I guess the idiom is being spoken to me the way the ancestors speak to me, and it gets mixed with my own comprehensions, my ignorance, my knowledge, my anger, my curiosity, and then gets translated into these works. I’m just the vehicle of all that.

*

Power Figures is Alexis Peskine’s first solo show in London. It will be exhibited at the October Gallery in London from September 13th until October 21st. There will be two works part of the series being exhibited at 1:54, held on October 5-8 at Somerset House, London.

Boy Dakar, 2016. Moon gold leaf, Nails, lacquer & varnish on Carriage (steel & wood), 4’ x 8’ x 4’. Image: Alexis Peskine. Courtesy October Gallery

Alexis Peskine

Born in Paris, in 1979, Peskine obtained a BFA in Painting and Photography at Howard University, Washington, DC, an MA in Digital Arts at Maryland Institute College of Arts in Baltimore, and when awarded the prestigious Fulbright Scholarship, he continued at M.I.C.A to complete a further MFA Degree. He has participated in many international fairs and exhibitions, including the 3rd Black Arts World Festival and the Dakar Biennale, Dakar, Senegal; Addis Foto Fest, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Frieze New York, Pulse Art Fair, New York, Miami Art Basel’s Prizm exhibit, Miami, USA; Biennale Internationale de Casablanca, Morocco; AKAA (Also Known As Africa) and Afriques Capitales, La Villette, Paris, France; and 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair, London UK.

Raquel Villar-Pérez

Raquel is an art curator and art writer based in London. She is interested in cross-cultural and intersectional dialogues established between different peoples addressing ideas of translocal identities in a world in continuous transit and movement, as well as in decolonial discourses within art practices from the Global South, mainly from Africa and Latin America, and how they resist the trends set by Globalisation.

She is very sensitive to women experiences and notions of transnational feminisms, and how contemporary art practices echo them. She tends to work collaboratively to open up participative processes to generate novel inclusive and progressive art narratives.