“The historical definitely has much to teach us today, in fact sometimes far more than the contemporary”, says art critic Athi Mongezeleli Joja. A recent exhibition of the Johannesburg Art Gallery – All Your Faves Are Problematic – proves that using history not always works out in the way he has in mind. “Most of the work shown in the exhibit coalesces around the voyeuristic and primitivistic impulse of the white artist, which over the last century has constructed black bodies as objects of anthropological and artistic fascination.“

Poster image of the exhibition

All Your Faves

The turn to the archive has, of late, dominated contemporary art discourse and whether or not it is a matter of coincidence or the result of the various declarations about the ‘end of history’ in the latter part of the 20th century, is neither here nor there. Whatever the case, this archival turn has pushed scholars and artists to plumb the depths of the historical. This is largely so because historical accounts exist somewhat obscurely today and are overshadowed by an urgent need to construct alternative futures on the one hand, or for the sole purpose of burying (which is to also say emptying) them once and for all on the other. When art historian Kobena Mercer asked why the “contemporary” takes precedent over the “historical” when it comes to issues of identity and difference, he understood how presentism easily facilitates forgetfulness. However, almost the inverse has occurred in South Africa where history hasn’t been forgotten, and appears unlikely to ever be. Instead, it has been returned to numerous times, instrumentalized even, and sold in every cultural kiosk as if it were a fetish or a charm that could paradoxically enable its own elision.

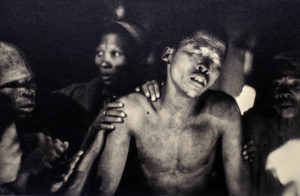

A photograph by Jürgen Schadeberg taken in the Kgalagadi when he accompanied palaeoanthropologist Phillip Tobiasin in 1959. Copyright the photographer

Khwezi Gule’s first show as director of Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG), All Your Faves Are Problematic isn’t quite speaking of history in this general social sense, but instead, in the tangential art historical co-riding of/with the historical. By tangential I am not implying that art and its history have no authorizing agency in the formation of reality. On the contrary, the history of art in South Africa has been taught or presented in somewhat benign ways, as a history of benevolent liberal endeavors of empathizers i.e. missionaries, explorers, multiracial workshop facilitators, the teacher amongst natives, the leftist, and so on. All Your Faves showcases a number of well known and relatively known works that have become staples in the diet of South African art. These include the likes of Irma Stern, Dorothy Kay, Cecil Skotnes, Jurgen Schadeberg, Paul Stopforth, Sue Williamson, Pippa Skotnes, Lisa Brice, Steve Hilton Baber, Peter Hugo, Jodie Bieber, and so on.

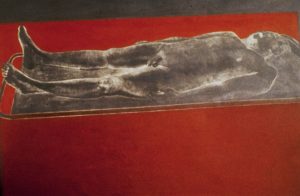

Paul Stopforth, Elegy 1981. Courtesy and copyright the artist

Most of the work shown in the exhibit coalesces around the voyeuristic and primitivistic impulse of the white artist, which over the last century has constructed black bodies as objects of anthropological and artistic fascination. From Irma Stern’s incorrigible obsession with the African subjects as raw material that titillates her canvas, to Walter Battiss’ neo-primitivist reconstructions of Bushman cave art, to Steve Hilton-Baber’s intrusive pornotropic displays of young male Sotho initiates, to Pieter Hugo’s thanatological obsessions with carcasses of black people, we encounter blackness as a perpetual curiosity for the white artist, not only available as an instrument of study but as a paradigmatic oddity necessary for the very existence of modern study. Though this isn’t something we can detect easily from other works, this underwrites much of global imaginaries in an antiblack world. This is so even though I might go further and argue that Paul Stopforth’s Biko Series, which allegedly shows the late Black Consciousness Movement leader Steve Biko’s “disemboweled” corpse, needs a more substantial critique than the one offered by the curator, and some reviewers. In this visual panoply, black people are often absent as actors and humans, but are rather present as what feminist scholar Hortense Spillers, calls “the being of the captor.” They are present as figments within a colonial consciousness, embattled by scenes of grotesquerie and wild fauna.

Pieter Hugo, Mallam Mantari Lamal with Mainasara, Abuja, Nigeria, 2005, Courtesy Stevensoin Gallery, copyright the artist

It is the capturing of this captivity that eludes Gule here. The clue to this is maybe in the title, All Your Faves Are Problematic. The use of the term “faves” (favourite) borrows from the current social media “call out” culture. “No one is immune, no one gets a free pass” reads the wall inscription in the gallery, with reference to the selected number of artists included from the gallery’s archive. Gule has named and shamed his targets. This after all is the ritual practice of this trend. But what we learn from the call-out however is that some names (and bodies) are more sacrosanct or immune than others. The title addresses an anonymous viewer (your) about the problematic nature of their preferred artists. The category of “faves” is synonymized with white artists, which indirectly implies that favoritism isn’t quite an outcome of neutral choices but of a larger conspiratorial, racially exclusionary practice of the South African art scene.

William Kentridge. Casspirs Full of Love, 1989, Courtesy Goodman Gallery, copyright the artist

But we must probe further. There’s something irksome about how this supposed calling out, somewhat circles back and re-centers whiteness in critical discourse. These are usually subjects whose works are already on circulation, never leaving the critical spotlight, from conference presentations, catalogues, exhibitions, and research precisely for the same reasons lamented by Gule. That, once again, a curator wastes the meager airtime allotted this fatigued and problematic subject-matter (that today only serves to help whiteness revise or rewrite itself), without any serious or useful insights considered beyond punctuating sections of the show with critical quotes and song, definitely is an unfortunate intervention. Although the quotes do pushback, they do so as mere extras in a dramatic scene that drowns out their individuality. Black people here are once more relegated to the margins, to be “curricula objects” (to quote Spillers once again) of white self-indulgent imagination. Of course, this isn’t to take away the importance of such a critique nor to discourage white artists from making art about whomever they want, even though the latter might be one’s intuitive stance. It is simply to highlight how crucial it is that it cannot be that racism is diagnosed only through the lens of those who enforce it but very rarely through those who refuse it. Gule’s denial of the latter’s voice, inadvertently makes him an accomplice to the same problematic he’s trying to reproach. It seems, although he “calls out” our problematic faves, he’s unclear about the actual problem at hand.

Thus we must heed Mercer’s insistence on the historical as the site of unearthing treasures deliberately excluded from the archival inventory of Western modernity, by refusing to turn black creative production into a footnote in modernity, and even in the contemporary. When art historian Hal Foster describes what he calls the turn to the archive as an impulse or an “idiosyncratic probing” into modern art and its intellectual history, he sees the artist as a critical figure and distinguishes it from what he earlier dubbed the modern artist as an ethnographer. This means that plumbing the depths of an archive may entail circumventing very presuppositions and methods adhered to, more so it’s authorial power. In another way, it is to refuse to take the easy route that leads to nowhere else but back into the same hell hole from which one is trying to escape.

Cecil Skotnes, Conversation, 1972

The historical definitely has much to teach us today, in fact sometimes far more than the contemporary. Here contemporary is understood, not in the myopic sense of “the now,” which is a description far less generative compared to Frank B. Wilderson, Giorgio Agamben or Peter Osborne’s recent treatises of the term. Gule’s probing or impulsiveness, despite its great reception, has its own problems, including its own faddish instrumentalism which unfortunately merely transposes social media culture without any deeper engagement with the problematic at hand. All Your Faves Are Problematic might be an exciting experiment with archival material but I truly do not know how it enriches a discourse on the racist nature of our visual culture.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja is an art critic based in Johannesburg, South Africa