(Alma Thomas, 1891-1978)

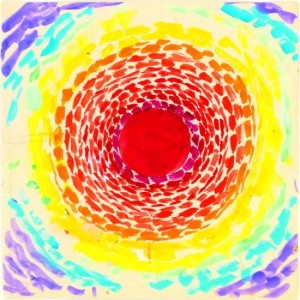

Untitled, 1970.

First published: December 1, 2014

About:

(fragment from an article of HOLLAND COTTER in the New York Times of October 11, 2009)

(…)Thomas was born in Columbus, Ga., in 1891, and moved to Washington in her teens. Her family settled in a house at 1530 15th St. N.W., and she lived there until her death in 1978. Her parents had relocated for two reasons: racial violence was on the rise in Georgia and Washington had excellent public schools. Thomas got a solid, though segregated, education, and taught art in one of the city’s junior high schools for 35 years.

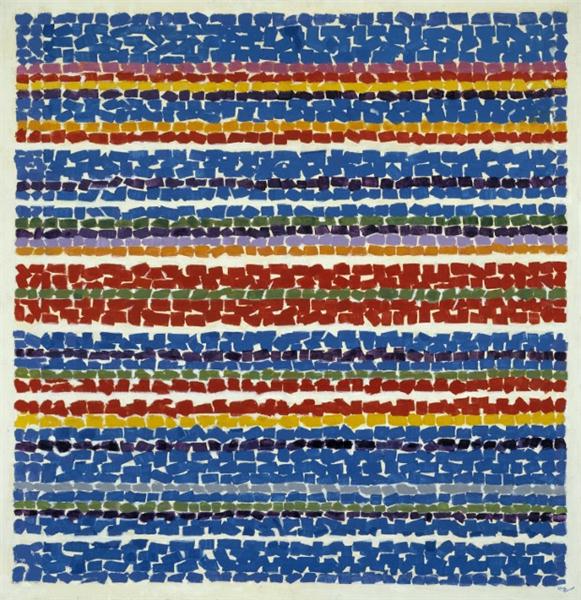

Azaleas in Spring, 1968.

Azaleas in Spring, 1968.

Before taking that job, though, she did other things. In 1921, she enrolled in a home economics program at Howard University, with an interest in making theater costumes. One of her instructors suggested she study art instead. She became Howard’s first fine art major, with a specialty in painting.

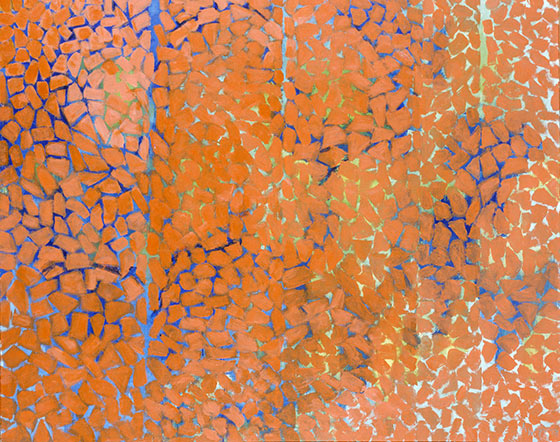

Light Blue Nursery, 1968.

Light Blue Nursery, 1968.

The painting continued sporadically during her teaching years. In the 1950s, she took weekend studio classes at American University, working briefly with Jacob Kainen, one of a group of abstract painters — Gene Davis, Morris Louis, and Kenneth Noland were others — gaining national attention as the Washington Color School. Thomas, who loved color above all else in art, always felt a kinship with them.

Hydrangeas Spring Song, 1976.

Hydrangeas Spring Song, 1976.

Only when she retired could she finally start to paint full time. She was 69. She used her kitchen as her studio. For subjects she took the trees outside her windows and floral plantings in local parks. She had once been an academic realist; then a semi-Cubist. Now she was ready for abstraction.

Autumn Leaves.

Autumn Leaves.

You can see her making the leap in the earlier of her two paintings on the White House list, “Watusi (Hard Edge),” from 1963. It’s an out-and-out steal of a Matisse collage. Thomas just shifts the pieces around, cools the colors down, and adds a title that refers to a Chubby Checker song. But through copying Matisse, she began to work out a format she would use again and again.

This consisted of short, block-like strokes of color lined up, like mosaic tesserae, in columns and bands set against a different color or unpainted ground. The second Thomas painting on the list, “Sky Light” (1973), is a classic, if somewhat somber and monotonous, example of the type: a wall — more like a fabric hanging — of close-together vertical columns made of linked blue strokes, with a white ground showing through, like light through cracks.

Watusil, 1963.

Watusil, 1963.

She kept playing with this model. She intensified the colors; laid light colors over dark. She went through a jazzy rainbow phase. She shaped the blocky strokes into chips, like puzzle pieces or pavement stones. She made the strokes sinuous and calligraphic, so they float and suddenly disperse like leaves in a wind.

White Roses Sing and Sing, 1976.

White Roses Sing and Sing, 1976.

Thomas herself was a popular favorite in her late-blooming career. Howard gave her a retrospective in 1966. In 1972, at 80, she was the first African-America woman to have a solo at the Whitney Museum. Critics raved. There was a second retrospective in 1977, and Jimmy Carter invited her to the White House. People couldn’t get enough of her. Why?

Her art was accessible. Her abstraction was never really abstract: you could always see the nature in it: flowers, wind. Her paintings were modern but part of some older tradition too, as close to quilts as to Matisse. In a racially charged era, her art wasn’t political, or at least not overtly so. When asked if she thought of herself as a black artist, she said: “No, I do not. I’m a painter. I’m an American.”

Untitled.

Untitled.

Instead of talking anger, she talked color: “Through color I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” American museums, under the gun after their neglect of black artists, breathed a sigh of thanks.

But when Thomas said color what was she really saying? She vividly remembered being barred from museums as a child because of her race. A lifetime later, she acknowledged that things were still hard. “It will take a long time for us to get equality,” she said in an interview. “But what do you expect when whites closed up all the schools and libraries on us for so long? They know that schooling would give us our salvation.”

In many ways she’s an ideal artist, and power of example, for the Obama White House: forward-looking without being radical; post-racial but also race-conscious; in love with new, in touch with old. A genuine rainbow type. She would have enjoyed being in Rothko’s company, and she would have understood where Mr. Ligon was coming from.