Archibald Motley, Jr. (1891-1981)

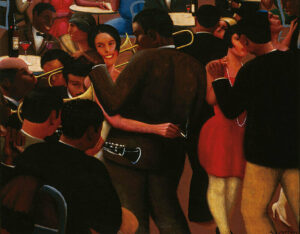

Blues, 1929

About:

He rose out of the Harlem Renaissance as an artist whose eclectic work ranged from classically naturalistic portraits to vivaciously stylized genre paintings. Motley’s work notably explored both African American nightlife in Chicago and the tensions of being multiracial in 20th century America.

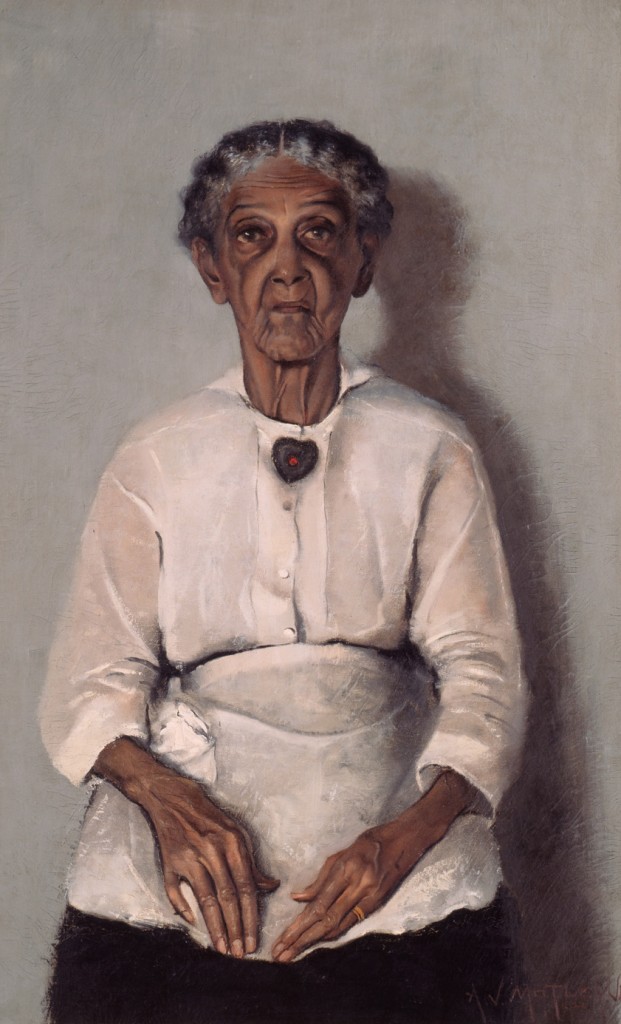

Portrait of mmy grandmother, 1922

Despite being born in New Orleans, Motley moved to Chicago at a young age with his parents, settling in the mostly-white, middle-class Englewood neighborhood. In Englewood, Motley’s family was able to live relatively comfortably. His mother worked as a school teacher, while his father served as a railroad car porter.[1] Motley’s formal study of painting began at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.[2] He benefited from the teaching of renowned realist painter George Bellows at the school, and graduated in 1918.[3]

During this time, Motley focused on using his artistic career as a means to ensure a place for African American artists in the American art canon. Influenced by the advocacy of Harlem Renaissance leaders W.E.B. DuBois and Alain Locke, Motley published an essay entitled “The Negro in Art” in the July 6th, 1918 issue of the Chicago Defender, a publication founded in 1905 for African American readers.[3][4] In the essay, Motley pressed for more creative opportunities for Black artists, and argued that they should receive legitimate recognition alongside their white counterparts.[5]

The Octoroon Girl, 1925

Racial identity became an apparent theme in much of Motley’s work, largely due to his own complex racial background. Motley himself had African, European, Creole, and Native American heritage, and was a lighter-skinned person.[1][2] As a result, many of his earlier paintings explored the relationship between multiracial people and the American cultural landscape. For example, Motley’s Mulatress with Figurine and Dutch Seascape (1920) depicts a woman with both white and African American ancestry and ambiguous racial identity, commonly called a “mulatto” in the early 20th century. Motley’s discernible and articulated brushstrokes ultimately blend and coalesce, as though to comment upon the dual nature of the interracial experience. The statue on the painting’s left depicts an idealized, classicized image of the muscular human body. It is as if Motley pushes viewers to reconcile the “mulatress” with the centuries-old standard of superior physical appearance.

The interracial experience was also the focal point of Motley’s award-winning 1925 piece, The Octoroon Girl. This painting presents a formally naturalistic depiction of a woman with one-eighth black ancestry, his “octoroon.” Motley’s “octoroon girl” has an upright posture and direct gaze, appearing relaxed and confident.[1] She holds a pair of gloves in her right hand, possibly suggesting that she alone holds agency over her racial and female identity or appearance. Consequently, Motley’s painting pushes forward both the racial and gender equality agendas. The Octoroon Girl went on to win the Harmon Foundation gold medal in Fine Arts, a prestigious award recognizing art from the Harlem Renaissance movement.[3]

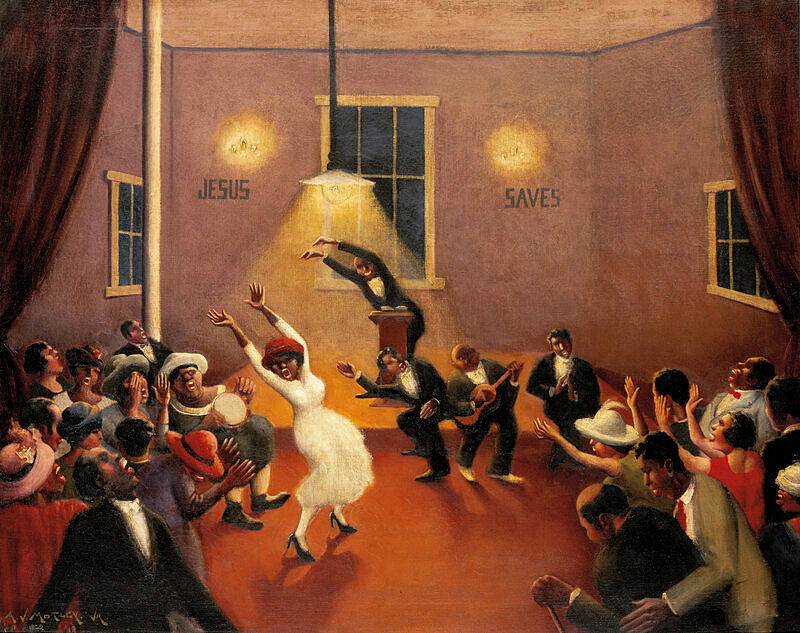

Tongues (Holy-Rollers), 1929.

In 1924, Motley married Edith Granzo.[2] Motley and Granzo, who was white, had one son, Archibald J. Motley III, in 1933. Granzo’s family, who was of German descent, disowned her because of her interracial marriage; Motley’s son recalls how the family maintained a private lifestyle due to persistent racial scrutiny.[1]

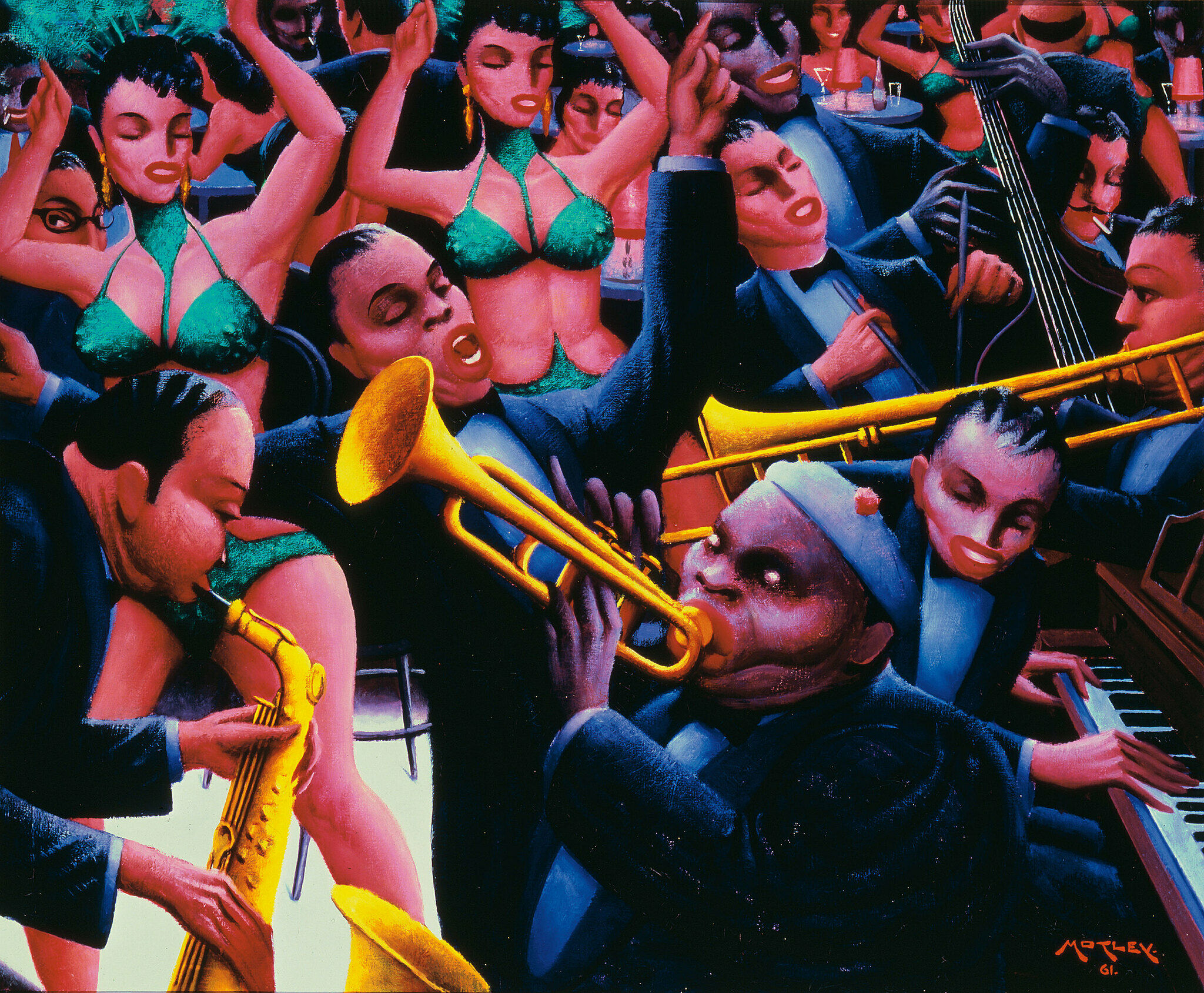

Hot Rythm, 1961

From the 1930s onward, Motley’s art began to examine the nightlife in Chicago’s predominantly African American Bronzeville neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. [3] Adopting colorist and modernist techniques, Motley’s Black Belt (1934) presents an image of Bronzeville at night.[1] The viewer is particularly voyeuristic in this scene, gazing out upon the active and bustling neighborhood. In Black Belt, one can see how, during the 1930s, Motley began to prioritize rich color and stylized shapes as a way to convey the energy of African American nightlife in Chicago at the time. Motley’s Hot Rhythm (1961) achieves the same effect, portraying the dynamic and lyrical qualities of jazz, departing from his earlier, more traditional portraits.[2]

Toward the end of his life, in 1980 Motley received an honorary doctorate from the School of the Art Institute. That year, he was recognized with nine other African American artists by President Jimmy Carter at the White House.[4]

In 1981 Archibald Motley died of heart failure at the age of eighty-nine.[5]

[1] Helal, Dina, et al. “Teacher Guide: Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist.” Whitney Museum of American Art. October 3, 2015. Accessed June 4, 2020.

https://whitney.org/Education/ForTeachers/TeacherGuides/ArchibaldMotley

[2] Gómez, Edward. “Archibald J. Motley, Jr.’s Paintings: Modern Art Shaped by Precision, Candor, and Soul.” Hyperallergic. March 9, 2014. Accessed June 2, 2020.

Archibald J. Motley, Jr.’s Paintings: Modern Art Shaped by Precision, Candor, and Soul

[3] Blumberg, Naomi. “Archibald Motley.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. January 21, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Archibald-Motley

[4] Reich, Howard. “Some key moments in Archibald Motley’s life and art.” Chicago Tribune, March 20, 2015. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/ct-motley-music-timeline-20150320-story.html

[5] Osborne-Bartucca, Kristen. “Archibald J. Motley, Jr. Artist Overview and Analysis.” The Art Story. October 25, 2018. Accessed June 8, 2020. https://www.theartstory.org/artist/motley-archibald/life-and-legacy/

This artist’s biography was written by Noah Hochfelder, the 2020 Norman Rockwell Museum Walt Reed Distinguished Intern. Noah is a rising junior at Middlebury College in Vermont where he studies the humanities and arts, with a primary focus on English and American literatures.

Illustrations by Archibald Motley, Jr.