What I have seen now is a couple of bad exhibitions (the reginal presentations and the Pop-Up show), but more importantly, a number of solid, interesting and sometimes great exhibitions. They showed works that were invisible for many years, they showed new works of promising artists, they showed a fruitful mixture of young and old, they made comparisons possible with artists from the region, on the whole they created an inspiring picture of the Caribbean.

Rob Perrée on the art in Carifesta XIII.

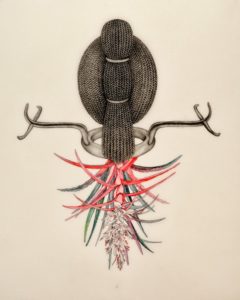

Versia Harris, Incipience No 2, 2017.

ART AT THE CARIFESTA XIII IN BARBADOS

Supporting actor on a stage dedicated to entertainment

“CARIFESTA embodies Caribbean integration. It is here that the people of the Region come together; co-mingle, creating one community, one people. That is integration. Further, this event strengthens the bonds between us, displays our creativity and ingenuity and demonstrates to the world the best that this Region has to offer. CARIFESTA celebrates our Caribbean being in a way that no other single event can.”

These are the words of Edwin Carrington, the former Secretary-General of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM)

Barbados sought to be the host of CARIFESTA XIII at this time, as we have in the last two years put in place instruments and mechanisms to position the cultural industries as strategic platform for economic growth. And since CARIFESTA represents the world’s largest gathering of Caribbean arts and culture, it is an ideal time to leverage Barbados’ infrastructural strength to assist with the development and promotion of the region’s cultural industries.

These words are paraphrasing the message of the Minister of Culture of Barbados, Stephen Lashley.

Idealism versus realism? Creating a community or creating money? My short and first visit to Barbados can provide only partial insight into heart and the matter of Carifesta XIII in Barbados. Apart from that, since the visual arts are my field, I will limit myself to that particular part of the event.

The first Carifesta took place in 1972. (British) Guyana was hosting. The initial intention was to organize a cultural festival on a regular basis, each time in another Caribbean country.This was not the way things actually happened. Although the last two were on a biennial schedule – 2013 Suriname, 2015 Haiti – most of the time it took longer to get the next one together. Lack of money will have been the main cause, although, I can imagine that the organization of an event of that scale must have been too big of a challenge, especially when the infrastructure of a country is underfunded. That explains perhaps why some countries took the responsibility (or the pleasure…) more than once (Trinidad 3X, Suriname 2X, Barbados 2X) and other countries had to leave the honor to better equipped ‘brothers’ (for instance Cayman Islands).

As the minister of culture of Barbados did not hesitate to repeat at every openings speech (“he loves to do them. He wants to be the next prime-minister”): Barbados invested a lot of money in more than 500 events: film, theater, music, literature, heritage, arts and crafts, food and visual art. More than an average person can ‘digest’ during his or her whole life.

Journey to one Caribbean

The first exhibition I saw was ‘Journey to one Caribbean’, installed in a shopping mall – Norman Centre – in the center of Bridgetown. A good location to reach a bigger audience, but not an ideal location to present works in a proper way. The title refers not only to the past – Barbados was a country from where slaves were distributed over the world, like Curacao – but also to the ideal of a Caribbean that acts more as one unit. Of course quality was the first selection criterion to bring these 36 artists from different countries together, but for curator Janice Whittle there was another important reason to select the artists she liked to present: she wanted to give the floor to artists who have not had many chances over the years to show their work because of the limited infrastructure of the island: Barbados – as most of the Caribbean countries – does not have a museum for modern or contemporary art; a National Gallery has been a subject for discussion for countless years, but it never got of the ground; the Queen’s Park Gallery – a governmentally managed institution – was closed for years and commercial galleries came and went. They don’t have a long life because the market is too small and too fragile. Result: a lot of artists make interesting work that stays invisible to art lovers.

‘Journey to one Caribbean’ is a solid exhibition with good work of artists like Arthur Atkinson, Albert Chong, Joyce Daniel and Philip Moore and with a number of eye-catching highlights.

Nick Whittle, Ancestors, 2017.

One of the highlights was the installation ‘Ancestors’ of artist-poet Nick Whittle. Whittle is British by origin. He moved to Barbados in 1979. He uses various media to express himself: installation, collage (“I like the playful aspect of it”), performance and film, among others. Recurring themes in his work are the journey, eroticism, spirituality, the sea (“I’m using the sea as a metaphor for all sorts of meanings, whether it’s the birth, the rebirth, the womb, this whole idea of life changing, everything changing, the cycle of things.”). The underlying theme of this work is the colonial past, more specifically, the position of a white Englishman in post-colonial Barbados. He wants to deal with this past, but does he have the right as a white person to talk about it, to refer to it? In ‘My Land’, one of his best known poems he speaks about this dilemma:

my land

this

is not my land

is not my right

my white skin

not from st john

nor strathclyde or

lamming’s belleville

but my skin is white

all the same

*

taxi sir

*

(a fragment)

![RheaSmall20170816_141640[1] (2)](https://africanah.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/RheaSmall20170816_1416401-2-1024x576.jpg)

Rhea Small, installation view, 2017.

Another remarkable work was the fiber installation of Rhea Small. It refers to the sugar industry of Barbados, for long the most important export product of the island, long since replaced by tourism. Fiber cane is the product that remains after sugarcane stalks are crushed to extract their juice. Small uses it in different forms and ways and, by doing that, she creates quiet islands amid a lively environment.

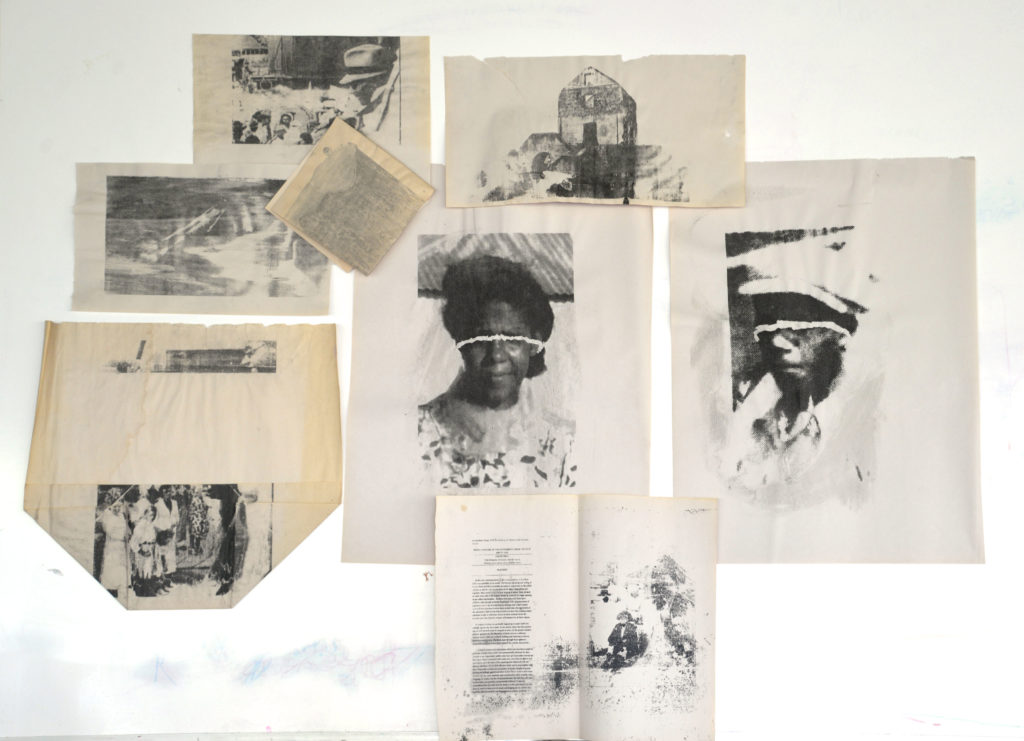

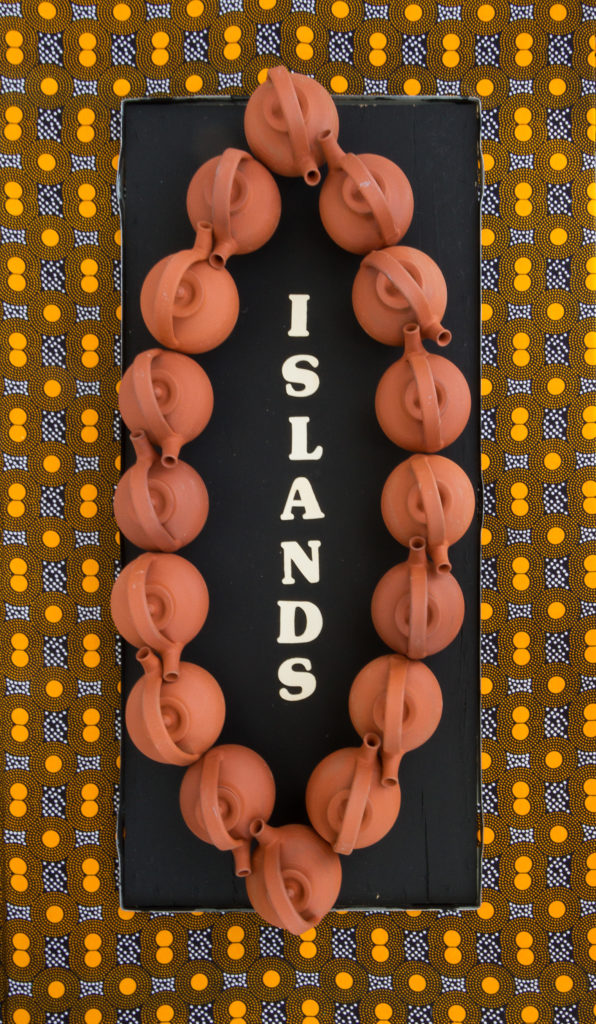

Simon Tatum, Discover Rediscover, 2017

Surrounded by all these more or less established artists is a young artist from the Cayman Islands: Simon Tatum is 22, he makes ceramic sculptures, drawings, installations and assemblages. He often uses existing, historical images and brings them to the present by editing and manipulating them. He draws on them, he puts image layers on top of each other or he intervenes in the (re)printing process. This work is an example of the way he works. An artist to keep in mind. (https://www.voyagerart.info/portfolio).

*

Masters

‘Masters’ is not only a wonderful exhibition it is based on a very interesting concept that, I hope, gets following in the coming Carifestas. Curator Therese Hadchity talks in the catalogue about “use – and activate – the works of a few to highlight some of the themes and questions, that have engaged many of the region’s artists for the last few decades”. She clarifies it as follows: “(…) a general premise for these practices has thus been their focus on matters of collective importance (…) origins, history, cultural self-assertion, regional integration and global dynamics, and, trailing right behind those preoccupations, about the assumptions, biases, silences that have suffused Caribbean historiography and effected the region’s pursuit of a distinctive identity.”

*

Hadchity selected Stanley Greaves (1935, Guyana, Barbados), Nick Whittle (1953, UK, Barbados), Joscelyn Gardner (1961, Barbados, Canada), Ernest Breleur (1945, Martinique), Ras Ishi Butcher (1960, Barbados) and Petrona Morrison (1954, Jamaica).

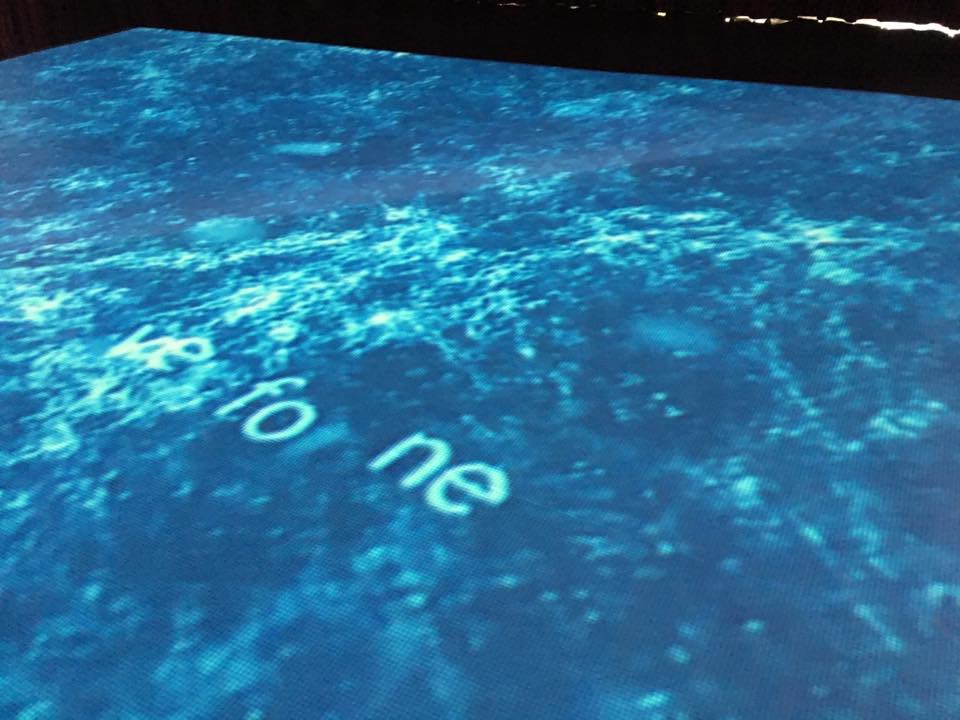

Joscelyn Gardner, Omi Ebora (Ode to Zong), 2014.

One of the ‘Creole portraits’ of Gardner.

Gardner presented the video- and sound installation Omi Ebora (Ode to Zong, 2014) in the Grand Salle of the Central Bank. She tends to dig up the history that many Caribbean people prefer not to talk about. She did that for instance with her ‘Creole Portraits’. In this installation the Middle Passage is the subject. She projects images of a violent sea in which words are popping up and than disappear in the depth. The words are quotes from the poet Nourbe Se Philip, but they are mixed with possible quotes of victims. The texts are also coming out of sound boxes. When I was there, the AC did not work. Smell was added. The mixture of image, sound, and smell made it a anxiety provoking experience…..

Stanley Greaves, The Annunciation, 1993.

The paintings of Greaves – with the works of Whittle and Butcher installed in the beautifully renovated Queens Park Gallery – are figurative, precise but always with a surrealistic twist. They look like scenes out of a dark and mysterious theater piece. They often refer to political issues. Politicians who love the microphone, to hear themselves, but don’t care about the audience. ‘Normal people’ are therefore often missing in his paintings. Greaves tells stories authorities don’t like to hear (see).

Petrona Morrison, Selfie, 2017, video still.

The 3-screen video installation ‘Selfie’ (2017) of Petrona Morrison deals with a kind of identity crisis caused by social media. A lot of people are portraying themselves constantly by making selfies. They are posing, trying out several perspectives, sometimes completely loosing themselves in that process. The selfies are distributed immediately among their followers. Is it uncertainty? Is it an ego problem? Is there a growing distance between reality and this representation of it? Morrison sets off an interesting discussion.

Ernest Breleur, Reconstruction of a Lost tripe, 2003.

Ernest Breleur – together with the installation of Morrison installed in the gallery of the Synagogue – used x-ray images as a basis for this installation. He cuts them, deforms them, attaches them, and creates in this way a cloud of images falling down from the ceiling. The title – ‘Reconstruction of a Lost Tripe’ (2003) – is the only content indication the puzzling viewer has. For most of them the ‘tripe’ can’t be found. And that is exactly what the artist had in mind, I think.

Nick Whittle, Homage to Kamau, 2017.

Nick Whittle showed a number of (wall)sculptures with the form of a boat as a basis. He is also referring to the Middle Passage, the transport of slaves under inhuman circumstances, the prosperity of cities like Glasgow – his mothers birth place – as a result of it. However, he makes it more personal. One work – ‘Merchant City Cross’ (2017) – says it all: ‘My Land is not this Island’ is the text on the upper part of the cross. The dilemma of a British artist who is generously adopted by a former colony.

Ras Ishi Butcher, Dario secreto siete, 2008.

Ras Ishi Butcher showed a couple of paintings out of his ‘Secret Diaries’ series. On a grey-black background he draws and paints small, framed stories. Sometimes they are more like symbols or icons, sometimes they are sketches of heads and faces, on other occasions they are (details of) landscapes. Overall they tell the story of a black man living in a former colony. By choosing symmetric forms he seems to put order in the chaos of his life.

*

The Impression

The exhibition The Impression is sited at the Morningside Gallery of the Barbados Community College. According to curator Nyres Rudder The Impression is “testimony to the incredibly personal intuition, perspectives and exploration of archetypal themes of identity, fantasy, folklore, music, religion, gender relations, industrial construct, entertainment and the natural landscape within a post-colonial independent island society.”

Versia Harris, Incepience no 1, 2017 (copyright of the artist)

Kraig Yearwood, J’Ouvert Morning Venus, 2015. (copyright of the artist)

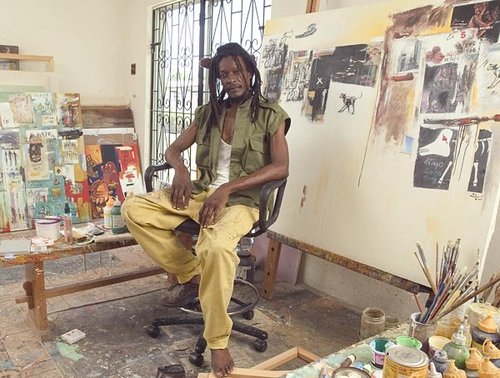

An unnecessary mouthful for a very nice exhibition of diverse works of young and somewhat older artists. The layered, deep black drawings of Versia Harris are not only beautiful, but they are also the surprising result of a research process in the possibilities of the mixing of different media: drawing, print and animation. An international career must be possible for her. Interesting too are the Basquiat-like paintings of Ras Akyem Ramsay, the detailed drawings of Simone Asia in which realism and abstraction loose their meaning, the simple, direct photos of Lesley Taylor and, not to forget, the unfolded boxes of Kraig Yearwood. They expose in a collage-like way the dramatic stories of his troublesome love-life. The ground colors – yellow or blue – are open to further interpretations.

Ras Akyem Ramsay in his studio.

In this exhibition I would expect to see works of talented artists like Mark King, Ewan Atkinson and Sheena Rose. Why they were not selected, I don’t know.

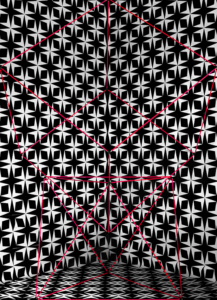

Mark King, Umwelten, 2015 (copyright of the artist). Mark King, Room 3, 2017 (copyright of the artist).

In his recent photo work Mark King combines art with fashion design and science. After a thorough research process he abstracts (existing) realistic images into forms and patterns. He uses the result as the space or the stage for a ‘construction’ of lines or to portray a human being dressed in abstractly designed clothes and de-humanized by a geometric from that covers the face. He challenges the notion of form as an element that refers to itself or form as a decoration tool without content.

Ewan Atkinson, one of the posters of the Neighborhood Project.

Ewan Atkinson is known for his subtle narrative drawings in which reality meets fantasy. More interesting are his projects Playing House and The Neigborhood Project. The first project investigates the influence of education on character development. In the second he, in his own words, “investigates the development of persona and character within the social boundaries that might define or confine a community. Conflicts between community and the individual are explored and interrogated.” Queerness is another important theme in his work. Next to drawing, the photo is an important medium to express his ideas and concepts with.

Sheena Rose, from the Invisibles series (copyright the artist)

Sheena Rose is a talented and popular artist. She knows how to promote herself. On social media you can follow all her ups and downs, her private life and her creative struggles. Her drawings and animations portray the cities she visits in an illustrative style. Her ‘Invisibles’ show more content and more freedom of expression. By calling them invisibles she belittles them. Sometimes her ego hinders her to look more critical at her work.

Regional Visual Arts Exhibitions

In the same complex were the so-called Regional Exhibitions installed: a group show of works from all the participating countries and individual shows of each country in separate rooms. This event made clear why a lot of artists don’t want to participate in Carifesta. In between the sometimes hundreds of other activities, fine art always played a modest role. The focus of Carifesta was and is mainly on entertainment. Partly because of that, the exhibitions within the previous Carifestas were often very disappointing. This regional presentation is another sad example of that problem. I don’t mean to say that the presentations were too traditional, not contemporary enough – a pleasant visit to architect/collector Mervyn Awon convinced me again that the Caribbean has a rich art tradition that is more than just worth to be shown – the problem was a lack of basic quality. As a serious, professional artist you don’t want to be part of it.

*

Art in Barbados

In between openings and official visits I have talked to artists, curators, organizers and art lovers to get an impression of the art scene on Barbados. It is a small and divided art scene. Small I knew, but divided surprised me. “The established artists take away all the possibilities.” “As a young artist you don’t have any chances.” “Art is still painting here.” “I never go to openings. They are of no interest.” These are some of the remarks I collected.

Of course it has a lot to do with the lack of possibilities and facilities on the island. There is no National Gallery, so nobody has access to the art history of Barbados. There are no commercial galleries, meaning, it almost impossible to show your work. That, in combination with a small market, makes it very difficult to find buyers for your work. Every artist has a job next to her or his art practice. There is no serious press to build up a useful tradition of art critique. How do you get necessary feedback of what you have created? Although it sounds simplistic, it is still an important factor: Barbados is an island and islands tend to isolate themselves. Of course there is internet and nobody stops an artist to be active and set up his or her own international network, but artist’s life would be a lot easier in a country where the facilities are easy to find and use.

Fresh Milk

In 2011 the artist Annalee Davis founded Fresh Milk, an independent organization that “supports excellence in the visual arts through residencies and programmes that provide Caribbean artists with opportunities for development and foster a thriving art community.” It is Fresh Milk’s vision “to nurture, empower and connect Caribbean artists, raise regional awareness about contemporary arts and provide global opportunities for growth, excellence and success. “ That sounds like the right answer to a too limited local situation.

I am wondering if it works like that.

Fresh Milk gives artists more possibilities like commissions, studio space, international exchanges etc.; it has built an impressive international network; it knows how to use the media to promote its activities; it organizes interesting meetings with specialists and colleagues from comparable institutions, all qualities that are indeed often missing in the “established Barbados art scene”, as it was called by many people I talked to. But……there is a big but. Fresh Milk works with a small, select group of artists and it is not interested in reaching out to a big audience. When I visited a meeting, there were not more than 15 visitors, obviously the expected crowd because they all knew each other. If you look more thoroughly at their projects, you must admit that they are promoted big and efficiently, but that they are less impressive in reality. At the openings of the Carifesta exhibitions I did not see anybody of ‘the Fresh Milk crowd’. They seem to operate in chosen isolation. Since there is no comparable institution on Barbados to make them more competitive, Fresh Milk can be its glorious, incestuous self. It does not stimulate the art on Barbados much.

*

Carifesta and art

Did Carifesta XIII serve the visual arts? I did not see all the Carifestas of the past. What I have seen now are a couple of bad exhibitions (Pop-Up and Reginals) , but more importantly, a number of good, interesting and sometimes great exhibitions. They showed works that were invisible for many years, they showed new works of promising artists, they showed a fruitful mixture of young and old, they made comparisons possible with artists from the region; on the whole they created an inspiring picture of the Caribbean. That is more than what I could hope for. In that sense Carifesta XIII worked out. Within the whole event however the visual art was not more than a supporting actor. The leading role was awarded to other, more entertaining and profitable ‘actors’.

*

The government of Barbados has to invest in a better infrastructure for art. In one of his opening speeches the minister of culture called art an “important economic factor”. That could be true – in big cities like New York, London, Paris and Amsterdam art tourism is an indispensable source of income – but it is only possible if a city or a country makes art a priority, meaning, shows real interest in it and is willing to put serious money in it.

Did Carifesta XIII “strengthens the bonds between us”, as former Secretary-General Carrington hoped for. That is hard to say. The participants had at least the chance to bond, I don’t know if the visitors of the activities were ‘guests’ from other Caribbean countries or mainly Barbarians. It needs a serious evaluation to find out in order to take wise decisions about coming Carifestas.