These works of art are an expression of activism against a system that is designed with such bias. Whilst it is true that not every police officer is racist, it is even truer that guilty parties do benefit from an inherently racist system. White supremacy, racism and oppression are still alive but art crosses the boundaries society tries to exclude others from.

Christabel Samuel on art of the #BlackLivesMatter movement

Art of the #BlackLivesMattter Movement

As social activism goes the #BlackLivesMatter movement has had phenomenal impact on the cyber landscape as well as our collective consciousness. It has emerged as the third most used social cause hashtag on Twitter racking up over 11.8 million appearances since its arrival in mid-2013. With movies like Get Out pushing the message and even t-shirt slogans brandishing the hashtag, the zeitgeist of our generation is one of protest against the atrocities faced all over the world. It’s not just developing countries we look to now; the world’s gaze is turned to Western societies like the United States. This is where another contemporary Black Civil Rights movement has formed, less than 60 years after Martin Luther King Jnr. The #BlackLivesMatter movement was created out of protest against a long history steeped with cultural significance which echoes the brutality of the 1960s.

It is clear from recent news that ‘terrorism’ is not just committed by people of color. Sometimes it even wears a uniform. Sadly those with the power to protect and serve have abused it, but a more encouraging result of these actions is the inspirational work that it has produced. Borne in the hearts and minds of people, artists and novices alike, the art work of the #BlackLivesMatter movement varies in style and content but is always emotive and evocative.

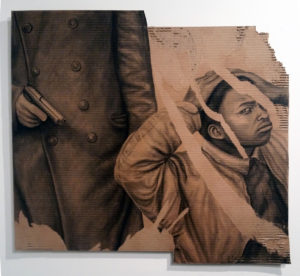

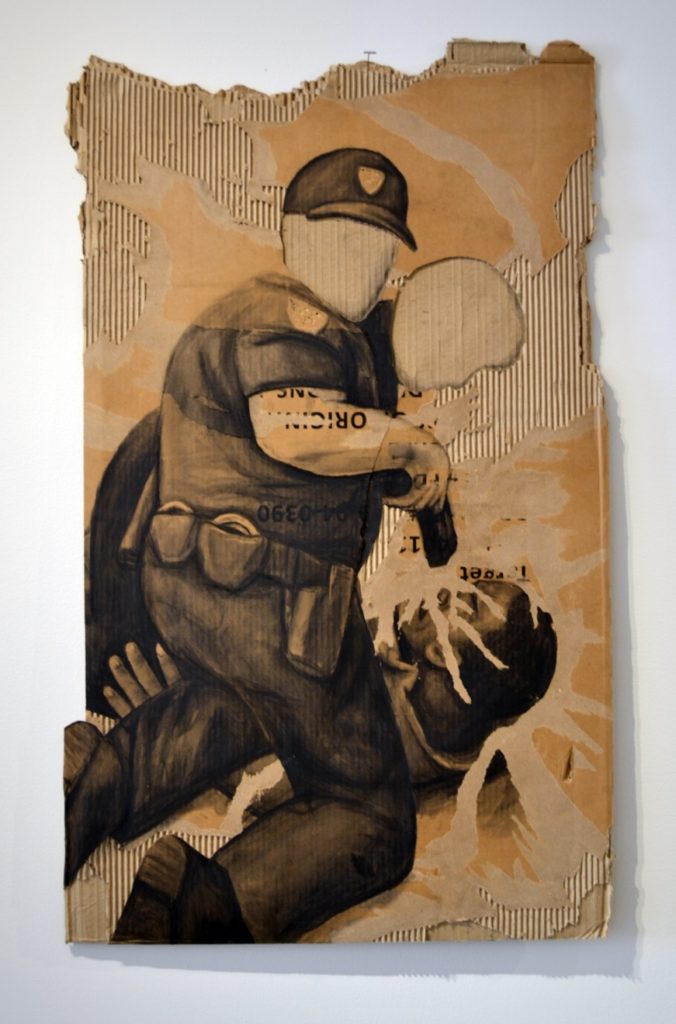

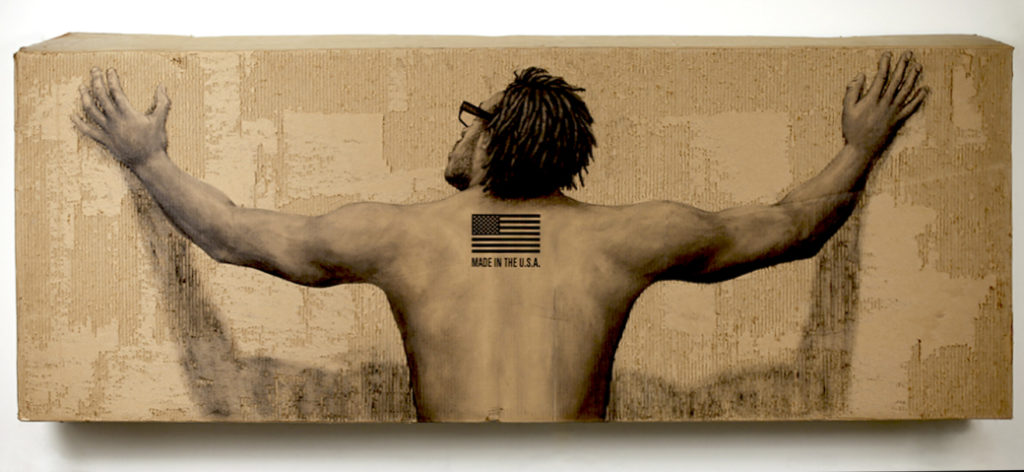

Dáreece Jordan Walker a Visual Arts student living in New York examines Liberty and [In]Justice for all? in his work, as well as Force/Resistance currently on view at the CS Fine Arts Centre in Colorado College. Not just comfortable in a gallery, Dáreece’s art has also been seen in protests at Union Square in New York and in front of the Florida courthouse during the George Zimmerman trial (Zimmerman was later acquitted for the second-degree murder of Trayvon Martin).

Walker explains that, the experience of growing up as a black man in the United States has yielded many questions for me about my treatment as an American, and the history of this nation as it relates to black people. These questions provoked my interest in black representation throughout history and in contemporary society. My aspirations are to challenge viewers’ perspectives on history and race equality in the United States. My current work is focused on police brutality and the riots following police shootings of young unarmed individuals. I use cardboard because of its color, layered texture and association with shipping and sales industries, and because it is a low-quality, easily damaged and replaceable material. All these aspects make cardboard a metaphor for the black experience. As a black male, I empathize with this material. The black and white paintings are on vinyl (indoor/outdoor signage material). This material is used to send a message and like cardboard it is often used as protest sign material. Through this work I critique the current sociopolitical climate regarding race and minority equality in the United States.

In his above piece entitled Criminalized 4 Walker’s use of cardboard tear-always add another layer of meaning. By removing the identities of the police and then outlining the victim’s blood splatter, this device links the officers with the violence whilst also highlighting the ‘cheap’ value of black lives. This is the ‘black experience’ for Walker and for many of the black communities who live in fear. The man in the picture is unarmed and overpowered and yet the perpetrators are anonymous and as such they are invulnerable and inculpable. Art here imitates life.

Another piece drawn with charcoal on cardboard called Made in the USA shows a black man, arms outstretched against a wall. On his back is a tattoo of the Star Spangled Banner and below reads Made in the USA. The title is maybe ironic, maybe patriotic but it is no accident that this juxtaposition is presented. For the generations of black people born and living in the United States; a place they call home, home is not a welcoming space, home does not mean equality nor does it feel safe. The blending of charcoal adds layering to the man; his hair, skin and shadow works with the charcoal to texture the piece. This medium also complements the cardboard, producing an almost sepia quality which invites a bitter nostalgia towards the growing number of black men who have historically assumed this position of arrest.

The #BlackLivesMatter movement is not just isolated to the United States. Its impact is felt globally; for those with relatives in America, for the black communities around the world and for everyone else who witnesses the brutality with sadness and horror. One such artist is Maria Maria.

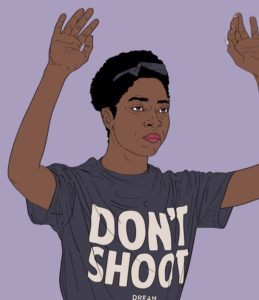

Maria Maria Acha-Kutscher is a Feminist visual artist. Originally from Peru and living in Madrid her work travels globally. Her focus is on the struggle for equality and the construction of femininity in culture. Committed to political transformation and answering a social need, her art is dramatically political.

For the #BlackLivesMatter campaign Acha-Kutscher wanted to bring the female narrative out. She says One of my greatest motivations as an artist is women’s history…I am interested in showing that political actions and social changes were always made by women and men together.

Her colorful stylized work gives a nod to pop-culture; the popular slogan t-shirts and No H8 campaign-esque duct tape is replaced with I can’t breathe and Don’t shoot. The messages on these black females are a chilling contrast against the clean lines and contemporary look of the drawing.

Acha-Kutscher asserts that art is a powerful tool. Most of the time, my work operates as an activist device for the defense of women’s rights. The intersection between art and activism is very interesting because it recognizes the conflict from another point of view. By creating new images that appeal to our senses, to our subconscious, we the artists are also witnesses of our time.

Perhaps the use of familiar iconography, young women and visually clean work plays out this conflict even better. The girls would not look out of place in a mall, everyday girls with regular lives and yet they, the artist and we the viewer bear witness to their vulnerability and despair.

The artistic space is not just reserved for black artists either. #BlackLivesMatter seeks to unite all people in the face of segregation. Ti-Rock Moore is one such example. Moore is a white artist who explains that the meaning and inspiration behind my work is constantly evolving but the common thread is addressing racial injustice and calling out the perils of white privilege. Since I’m a white artist I explore my message more from the perspective of the perpetrator of racism, which forces me to constantly be aware what I take for granted because of my racial identity and how that is contributing to the problem.

Hailing from New Orleans, Moore has always been aware of the white privilege and racism that has been a visible and salient reality. As well as championing LGBTQ rights, Moore continued her activism in the ‘80s and ‘90s, finding a passion for exploring the themes of racism. In 2014 she emerged with works of protest, in part a response to Hurricane Katrina but has continued with vigor to produce art that seeks to dismantle the structures that support racism.

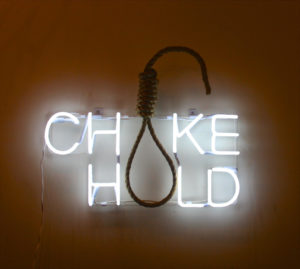

One such example of the striking and triggering power of her work is entitled Protect and Serve.

Moore states that the piece equates the history of lynching black bodies in the United States to modern-day violence against innocent black community members in the form of police brutality.

The photo’s fluorescent wording surrounds the noose in the centre, hanging forebodingly in the shadows. Not only does it summon the shameful history of lynching but Moore references here the death of Eric Garner who was choked to death in 2014 by a New York police officer. The history and background are tied together to create a bitter irony from past and present manifested in its title Protect and Serve.

On the subject of racism Moore believes there are two groups; the protagonist and antagonist, an Us and a Them. White privilege is something Moore does not shy away from acknowledging it as a direct remnant of slavery, she is aware of the advantage her skin color holds. White privilege controls America’s heartbeat, and our nations collective loss of memory, our historical amnesia, is to blame. I examine myself and identity in a critical manner; I hold my audience and me accountable for our complicity. Indeed, it is past time for white Americans to hold accountability for and stand up to the injustices of racial oppression.

Unfortunately racial oppression is a prevalent aspect of Western society and the atrocities in America are a painful reminder of this. These works of art are an expression of activism against a system that is designed with such bias. Whilst it is true that not every police officer is racist, it is even truer that guilty parties do benefit from an inherently racist system. White supremacy, racism and oppression are still alive but art crosses the boundaries society tries to exclude others from. Art crosses emotions that transcend gender, nation and race. These three featured artists are proof that the work born from the #BlackLivesMatter movement is just as loud, angry and unapologetic as the crimes they are protesting.