Ruga, in the absence of archives, might rely too much on fabulation. References to Greek mythology, Christian iconography, Xhosa cosmology, and queer aesthetics make for dense readings but crowded works. There’s a lot to unpack.

Keely Shinners on Dramatis Personae of Athi-Patra Ruga

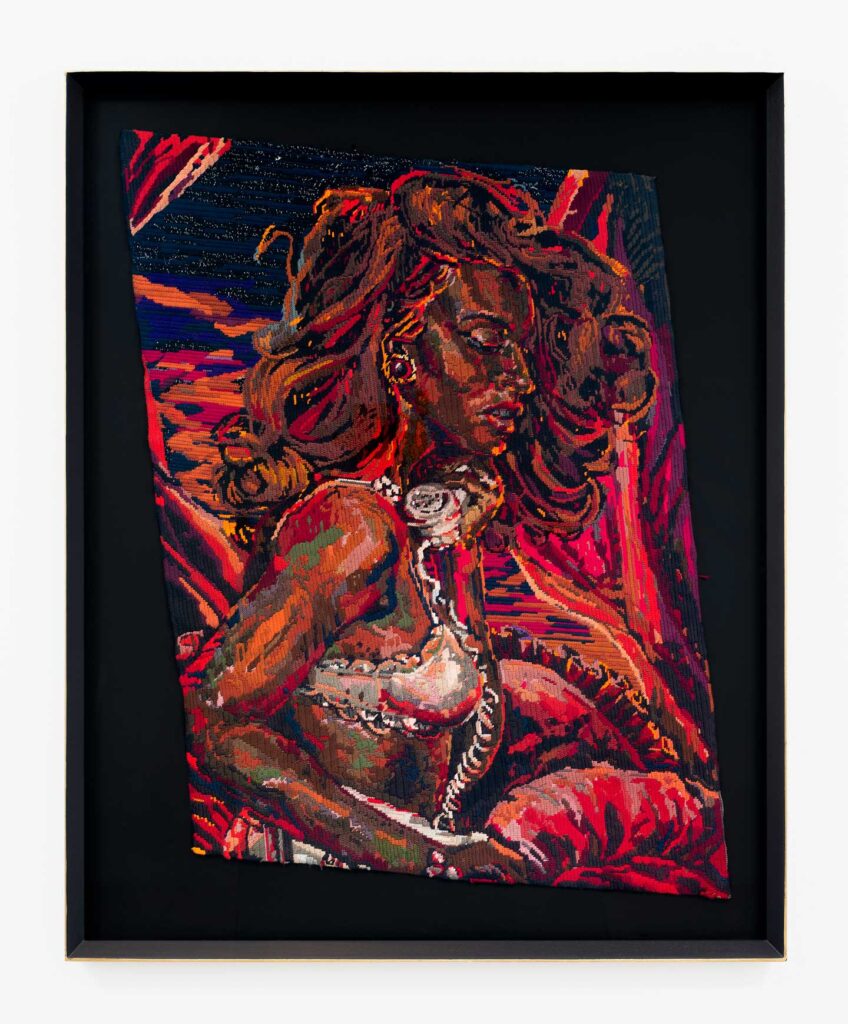

Sinyanga yekhala (detail), 2020

OVERWHELMING TAPESTRIES

Athi-Patra Ruga’s newest exhibition of tapestries, staged last year at Whatiftheworld in Cape Town, felt, in many ways, more like a theatre than an arts production, not the least because it was entitled Dramatis Personae. The room was dark; the portraits spotlit. The press release, less so a think-piece than a cast list. The roles are as follows:

Nomalizo Khwezi

A child prodigy who was extricated from her home in Ndema, Tsomo at age thirteen after she designed a poster for the Azanian Banks conscription campaign. Growing up in a prestigious boarding school under the patronage of Memnus Brink, she is later hired to work at his publishing company in Azania City.

Nobantu, Queen of the amaMpondomise

An Anglicised and Fort Hare-educated black elite woman, as depicted in AC Jordan’s Ingqumbo yemiNyanya, who is exiled after killing the revered snake, uMajola. Nobantu is something of an astral twin, or alter ego, to Nomalizo.

Memnus Brink

The owner of Brink Publishing in Azania City, which produces the nation’s textbooks. A propaganda campaign implicates him in the Azanian war.

Nestra Brink

Memnus Brink’s wife. She procures a lover and accomplice in Nomalizo when both their sons are sent to the front-line of the Azanian war. Together, they claim back ownership of Brink Publishing.

Translated from Ruga’s imagination into tapestry, these characters inform the four portraits which make up the exhibition: Ukusiba uMgubasi, uNobantu Nomajola, Inyanga yekhala, and Clytemnestra. Or, less so portraits than they are icons in an ongoing epic. An epic, I propose, which has less to do with imagining alternative worlds than it is about looking back at the past and reading in between the lines, in much the same way Saidiya Hartman does in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments.

Revisiting Hartman’s thesis, I can’t help but see its resonances with Ruga’s show: “The wild idea that animates this book is that young black women were radical thinkers who tirelessly imagined other ways to live and never failed to consider how the world might be otherwise.” [1] Though Hartman’s narrative is historical — centred on young Black women in America at the turn of the twentieth century — and Ruga’s fictional — a composite of memory, myth, and metaphor — the ethic is the same: to recreate from the radical imaginations of the overlooked.

Hartman does this expertly in prose. How does Ruga do it through thread? Crammed with color and symbolism, these tapestries can, at first, overwhelm the eye. But spend enough time with them, and a narrative starts to unfold:

Ukusiba uMqubasi, 2020

The first in this series, Ukusiba uMgubasi, depicts a young woman in a church pew. She looks cramped: shoulders hunched, church busy, walls too close, closing in. Perhaps, she is contemplating her future. What life might be awarded to a young Black woman from the rural town of Ndema, Tsomo? Makoti or nun, as were the fates of her mother and grandmother and their mothers before them. But Nomalizo is not like her mother or her grandmother. Nomalizo is a woman made of desire with her eye set on the horizon. Perhaps that’s the reason for her second name, Khwezi, ixiXhosa for Venus. Goddess of want. Morning star. What she wants is “an elsewhere and an otherwise.” [2] What she wants is “a notion of the possible.” [3] Colored orbs, like stars, encapsulate the amorphous edges of Nomalizo’s want, blinking affirmations.

The enclosed radius of her life in Ndema has an opening in the form of a patronage from Memnus Brink. But the problem with a patronage is that it’s on somebody else’s terms. They can decide what you make of your freedom; they can decide when the opening is closed. Which is why Nomalizo has come here, beside the sainted glass window of St. George as he puts a dagger through the serpent’s neck. “Believe in God and Jesus Christ, and be baptized, and I shall slay the dragon,” was what St. George said, or so the story goes. Is redemption another name for leverage? Nomalizo wonders. If someone offers you deliverance, what is owed? Why must my life be a currency in which others trade? Who charges interest on a dream?

uNobantu Nomajola, 2020

That night, I imagine, Nomalizo has two dreams. One looks like the tapestry uNobantu Nomajola. In it, Nomalizo is an older woman. She has taken the escape route, becoming worldly, educated, elite. Ornamented and bejeweled, she has a regal glare. At what cost comes respectability? The serpent is wrapped around her neck and doek. Her patience, as well as her resolve, are being tested. She is, at once, impressive and reviled, empowered and arrested, feared and subjected to fear. It is an ouroboursian life: the thing that feeds is the thing that kills. She, like Nobantu, is exiled. And not for slaying the serpent, but for embodying its power. For wanting the impossible which, for a woman, is the same as wanting anything.

Inyanga yekhala, 2020

The other dream is its diptych, Inyanga yekhala. Here, Nomalizo seems to have stayed at home. There is healing there, amongst the aloes, and stability, consistent as the moon. But Nomalizo has retreated to her internal world. What protest is Nomalizo harbouring? What complaint? What dreams go too long unreleased? Wrangled behind closed eyes, distant as the cosmos?

This is half the show: Nomalizo dreaming, Nomalizo becoming, Nomalizo suspended between two decisions, each with the potential to heal or endanger. Ruga suspends the viewer here: in the period before aspirations are corrupted or curtailed. We don’t meet Nomalizo again besides her voice on the other side of the telephone in Clytemnestra, the portrait of Nestra Brink. Between them, a kinship forms, and with it, some elbowroom. One errant woman may tire of swimming against the current of what people expect from her; two errant women just might blaze a path. Nevermind the intimacies that may form between two errant women in a glamourous, rose-hued room, cradled in plush fabrics, lush temperatures…

Clytemnestra, 2020.

What I first found confusing, and then found meaningful, about this narrative — this theatre in tapestry — is how queer it is. Not just because its actors are queer, but because Ruga’s is a story about becoming, transforming, refusing, overhauling, reclaiming. It is multilateral, nonlinear, punctuated with intimacy and foregrounded in dreams. It’s the kind of narrative that gets widely overlooked because it operates under the surface, in acts of negation and bouts of personal upheaval. It is, like Hartman’s book, “an account of the wayward.” [4]

“It is a narrative written from nowhere, from the nowhere of the ghetto and the nowhere of utopia,” [5] Hartman goes on to say. Ruga names nowhere Azania, defined paradise in previous bodies of work, however Dramatis Personae sees a much more precarious invocation of the term. But for Hartman, and perhaps for Ruga, the point of utopia is not foreclosed if unrealised. The point of utopia is to rail against the unacceptable. Which is why, I think, convoluted as they may be, Ruga’s mythmaking practices are important. A ‘myth’ is, anyway, a word used to refer to any knowledge system which does not ascribe to colonial narratives. Ruga operates in possibility, which is not the same as untruths.

Against the backdrop of a colonial archive — Koleka Putuma would call it collective amnesia [6] — possibility is often all one has to work. “Every historian of the multitude, the dispossessed, the subaltern, and the enslaved is forced to grapple with the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspective matters, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor,” [7] Hartman says. Her project endeavours to provide a counter-narrative to an archive which saw young Black women as a problem. And although she paints an immersive picture of their lives, she assures that nothing was invented.

Ruga, in the absence of archives, might rely too much on fabulation. References to Greek mythology, Christian iconography, Xhosa cosmology, and queer aesthetics make for dense readings but crowded works. There’s a lot to unpack; I worry that some viewers might get distracted by the onslaught of colors and symbols. And yet, there is something revelatory about this methodology. Immersing himself in the worlds of Nomalizo and Nestra, he returns with archetypes, allusions, ancestral whisperings.

There is an element of spell-casting to Dramatis Personae. Spell-casting as both reimagining the future and recuperating the past. It’s a way of saying, if this is what could have been, this is what could be.

Endnotes

[1] Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, pp xv.

[2] Ibid., pp 46.

[3] Ibid., pp 46.

[4] Ibid., pp xi.

[5] Ibid., pp xi.

[6] Putuma, Koleka. Collective Amnesia.

[7] Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments, pp xi.

Works cited

Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. (London: Serpent’s Tail, 2019).

Putuma, Koleka. Collective Amnesia. (Cape Town: uHlanga Press, 20