As powerful and impactful as Williams’ work was at the time – and as successful as he was as a solo artist – it is in relation to his work and service within the CAM that we can appreciate the movement as an act of political and social change. Through the members own creative talents CAM drove for a better representation of Caribbean life, art and community. Outwardly it reflected the culture of the time; it rebelled against white supremacy in Britain, brought its own flavour from back home and together sought to merge the two – much like the ethos of the Notting Hill Carnival.

Christabel Johanson about Aubrey Williams and the Caribbean Artists Movement

Sun Hieroglyph, 1983, ©Aubrey Williams Estate. Photo: Jonathan Greet

First published: October 6, 2018

Aubrey Williams and the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM)

The October Gallery in London are currently celebrating the work of the late Aubrey Williams. Williams, for those of you who aren’t familiar with his art, was part of an explosion of Caribbean writers, thinkers, artists and creatives that found themselves in London in the 1960s.

*

By the 1960s the Caribbean Artists Movement or CAM was in full force. Poets, historians and creatives constituted the collective and its inception came from a very specific set of social circumstances. At that time the connection between the United Kingdom and its former colonies were still strong which led to several educated Caribbean people immigrating to the UK for further study. In fact from the late 1940s onwards there was already an influx of West Indians moving and staying on in Britain due to the post-War shortage of labour and with the dreams of a better life for themselves. This was a continuation of movement between the commonwealth countries.

*

At the time the CAM were important in developing the “oral” form of writing and poetry, such as the distinct language and patios used by West Indian communities. This was a conscious art form of reclaiming a British-black identity and indeed the movement itself was aware of its own historical heritage and value, evidenced by the heavy documentation from its beginnings. Tape recordings were made and stored, almost a precursor of its importance as first-hand evidence from the time.

Book on the Caribbean Artists Movement

The CAM’s members were drawn from this Caribbean diaspora and formed a collective whose focus was on discovering their own style, themes and culture. This included old traditions, music, African heritage and other symbols of black identity against the British and white regime they found themselves in. In London John La Rose – a writer – along with Andrew Salkey developed the CAM with other artists including Aubrey Williams who was working as a painter at the time.

*

Aubrey Williams was born in Georgetown, British Guyana in 1926. He was already painting and had an agricultural job when he moved to England in 1952. He studied at St Martin’s School of Art for two years but dropped out before he graduated. Williams’ style was abstract and he found the school’s vision was restrictive against his own work. During this time he had exhibited his early work in West London shows. However it was not until the New Vision Group (NVG) found his art and embraced its abstract nature was he celebrated and displayed across the city from Marble Arch to Kingsway by 1958.

These shows really opened the door for the young artist, with international exhibits soon following suit. By the 1960s Williams was an acclaimed artist around the world and in 1965 he won the Commonwealth Prize for Painting. It was perhaps this fame that drew him to mind in 1967, during the first stirrings of CAM. Edward Brathwaite (another member and founder) had thought of Williams and so he was invited to their early meetings. During these discussions the small group talked about Caribbean identities in Britain, how to expose British people to West Indian culture and Caribbean art. With Williams being so well-read from his Guyanese education and with his status as a known artist, he helped develop CAM’s its strong literary side and spoke at many of the movement’s conferences in its later years, as well as contributing to their printed editions.

*

When it came to Aubrey Williams’ paintings, he was not afraid to veer aware from the norm. Britain had little black art work displayed until his breakthrough which in itself was a protest against the status quo and an assertion of the “Other”. Part of his style – the abstract form his paintings took – is a rebellion against classification. Although his “Otherness” was at first a symptom of his difference from white society, it later became a badge of resistance and signified blackness. Williams resisted an easy classification, exampled by his avant-garde depictions to his more refined work. Drawing on from science fiction to nature, he digested a broad range of inspiration for his work.

Shostakovich 10th Symphony Opus 93, 1981. ©Aubrey Williams Estate. Photo: Jonathan Greet.

The above is Williams’ interpretation of Shostakovich’s 10th symphony and was inspired by listening to the composer. He is quoted as saying Shostakovich’s music was “humanity in sound” and the strong colours characterise this energy. Emboldened against the backdrop, these large concentrated colours are like bursts of music in the form of painting. This is not an immediately obvious interpretation, especially if the title and background is not known. However this is part of Williams’ flair for abstract interpretation and his revolt against classification.

Carib Ritual IV, 1973. ©Aubrey Williams Estate. Photo: Jonathan Greet.

An earlier piece here exemplifies more of his abstract work and continues a similar colour motif of reds and warm hues punctuated by the whitish/grey shapes. Carib was one of the three main native groups in Guyana (the other two being Warrau and Arawak which he also painted) and this reminds us of Williams’ focus on native roots, ancestry and personal identity. He had a long-running concern with presenting a native culture pre-colonialization, and contributing to the understanding of a Guyanese identity. The frenetic shapes also are reminiscent of graffiti. Perhaps this is coincidental however this urban art form most certainly was associated with black culture and maybe this was another layering of rebellion against the white dominant society Williams found himself in.

Codex II, 1986. ©Aubrey Williams Estate.

Again Williams merges abstract patterns with traditional Guyanese iconography. The jaguar or big cat, the native shapes and animals represent a heritage from South America which predates European colonialization. The title informs us of intent to a degree as a “codex” is an ancient manuscript in book form. Thus Williams evokes the idea that non-white culture was in existence before white colonisation made it the “Other”.

*

As powerful and impactful as Williams’ work was at the time – and as successful as he was as a solo artist – it is in relation to his work and service within the CAM that we can appreciate the movement as an act of political and social change. Through the members own creative talents CAM drove for a better representation of Caribbean life, art and community. Outwardly it reflected the culture of the time; it rebelled against white supremacy in Britain, brought its own flavour from back home and together sought to merge the two – much like the ethos of the Notting Hill Carnival.

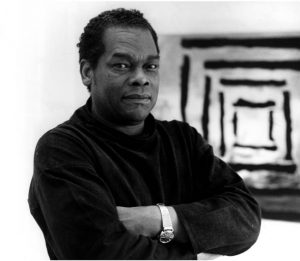

Aubrey Williams, 1926-1990, © photo Val Wilmer*

Before the CAM there were only creative pockets of artists working in isolation, but it was only after the merger of these people and art forms did real change happen. The Caribbean Artists Movement became more of a public organisation that had to fulfil public commitments; conferences were established, critical essays were published, even newsletters were circulated for its readership. This crystalized and formalized the thoughts of its members and contributed to its legacy. For example the critiquing of West Indian literature evolved from early CAM meetings. Caribbean literature was also introduced into schools and universities around the time of the CAM and was encouraged through its member’s teachings. Moreover academic texts have quoted the CAM’s work as inspirational – and within that work Aubrey Williams was one of the most gifted and non-conforming assets to West Indian art work.