“What I love about Home Museum is the sentimental value that all of us can relate to. It is not about the stars, but there to empower citizens.”

Azu Nwagbogu on the concept of The Home Museum

Portrait of Azu Nwagbogu and Clémentine Deliss in front of a sculpture of Ben Enwonwu outsde the National Museum of Nigeria, Lagos (photo: Ugochukwu Emebiriodo)

Home Museum and beyond: a museum from the inside out

After my interview with Dr. Clémentine Deliss and Azu Nwagbogu, I started to look enthusiastically and passionately for objects in my house that I could present in Home Museum: Rapid Response Restitution. This is the name of the central project in this year’s Lagos Photo Festival (2020). It is a call for a meaningful discussion about the return of important colonial-era African artefacts from western museum collections. Home Museum is meant to be the most radical form of the decolonization of museums.

Dr. Clémentine Deliss and Azu Nwagbogu are the initiators and co-directors of this new form of a museum and worked together with two guest curators: Dr. Oluwatoyin Sogbesan and Asya Yaghmurian. A young German-based, multicultural research cooperative ‘Birds of Knowledge’ designed the digital exhibition. 240 individuals from around the world responded to an open call that was spread via social media. A visit to the website of Home Museum shows that the participating photographers present often straightforward objects but that are imbedded in generations of family history and therefore full of valuable meaning. Clementine and Azu explain that objects are important to each person, family and home. Some treasures we use every day, some we keep, some we hold close, some we lose, and some are simply forgotten and not preserved at all. All these things bring back memories and tell stories about our culture and history in ways we do not always recognize.

No hierarchy

Azu continues: “What I love about Home Museum is the sentimental value that all of us can relate to. It is not about the stars, but there to empower citizens.” The museum of the future needs to be distanced from all existing hierarchy and opinions of experts and museum directors. That is also why the open call for Home Museum is translated in 12 languages, to make it accessible to everyone and take it from the elite or academic world. It is about building a network and moving away from an event-like project, such as a biennial. To also move away from other classifications, consequently texts are not edited, no gender, no geography and no age is displayed in Home Museum.

Examples from Home Museum

Nwannediuto Ebo shows eight photographs entitled ‘The left-behinds’. In the accompanying text she explains: “I have created a home museum from items that belonged to my grandfather and my two grandmothers, all of whom the earth now holds. My grandfather was a popular palm wine tapper. He was also a successful hunter. I have photographed the hunting guns, the bicycle, the palm wine gourds and the drinking horns he left behind. In his last years he stopped hunting, but the palm wine tapper in him never died until he did. My grandfather passed on almost 15 years ago but until today no one has been able to put away his things or scorch them as is usually done.”

Photograph: Nwannediuto Ebo

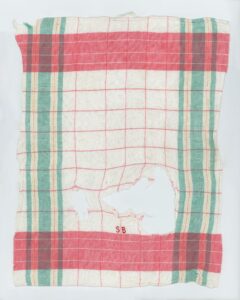

Another very touching personal story is posted by Eva Stenram: “A 1950s woven kitchen tea towel embroidered with my mother’s maiden initials. My mother, SB, was among the first women from her northern Swedish region to study at university. Yet she dedicated most of her life to being a wife, mother and housewife. This object is now worn out but can’t be thrown away. Rather than photograph the tea towel, I scanned it bit by bit and then stitched the different sections together. The digital work with pixels within photography echoes the handiwork that made the woven patterns of the grid. The towel is like a map that has ruptured, the destination obscured.”

Photograph: Eva Stenram

In Ayobami Akangbe’s museum there is also only one object presented: a stove. “The stomach rescue in my home is my stove, from my little and mettle I have always been able to survive even when I am on less and reach.”

Photograph: Ayobami Akangbe

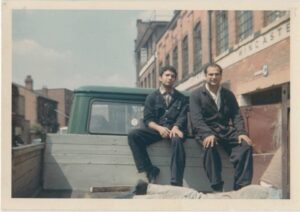

There are also photos of photographs in Home Museum. Shaista Chishty shows Daddy on Truck Work: “These photographs help to piece together the personal stories of my mother and father who moved to Birmingham from Pakistan in the 1960s. They tell the story of how they arrived, and some of the things they clung to, to help with the challenges of being so far away from home. Objects include letters, which were the main way to communicate with our family in Pakistan, the work permit my father came to Britain with, my mother’s first passport, old family photographs, a picture of their first Qur’an, and the first women’s magazine made locally in Birmingham for Pakistani women.”

Photograph: Shaista Chishty

Personal stories

It is very tempting to click on all the names and read what personal stories the photographers have written about their often carefully staged object(s). While visiting a museum I can sometimes feel alienated towards the objects as they are displayed as relics in majestic buildings. This is completely different in Home Museum which is personal, touching and easy to relate to. It makes me want to create my own personal page and I feel excited when I think of personal heritage objects that I would like to showcase. My personal history and therefore my identity is based on memories that I share with these objects that I cherish and most importantly what they represent to me.

Rapid Response Restitution

Now I understand what the initiators of Home Museum mean by the importance of preserving stories about culture and history on the basis of objects and why restitution of important colonial-era African artefacts from western museum collections is extremely important. Azu sighs wearily when he talks about the pushbacks regarding restitution: “You get pushed back by religion and infrastructural issues. Nigerian Protestants will burn down (pagan) artefacts and thus their own cosmology in their houses. Then there is always the discussion western museums use about African countries lacking physical and intellectual infrastructure for restitution of heritage. I feel like they need to trust more. They need to give back heritage like the Benin bronzes and also pay rent for the loans.”

Future Museology

Azu and Clementine speak furiously and passionately about their visions for the future (museums). They talk about the continuation of Home Museum. What it should be called is not yet known, but the word ‘generator’ is often being used: “Home Museum and its follow-up is a metaphor for a new framework to deconstruct the notions of colonial structure of museums, conservation, art history and curatorial ideologies. We need new notions in the art world, new language, new formats, new infrastructure and it will be organic by nature. We are now in therapy; it is a metabolic gradual process. We are interested in politics of independent art research. A moral imperative, not only sustainable but a radical new perspective is needed. With animated debates, less progress oriented but rethinking ways of using space… All ideas are embedded in future museology. We need to regenerate ourselves and pass it on to new generations. We don’t want to be gate keepers, but we want to share ideas and empower the new generation.”

After this inspiring conversation my brain is working overtime. I feel the urgency to take action, I want to take big steps, but I decide to start small and look around my house with my camera in my hand. I am looking for objects for my Home Museum, for my personal story to share, as if my house was a museum.