In November last year I started travelling in the Caribbean region, researching the sustainability of contemporary art practices and the influence of international (exchange) projects, funding, markets and politics. During my research I will be keeping a travelogue for Africanah. My first stop in the region is Ayiti (Haiti), one of the islands in the region I have not spent any time before.

Sasha Dees on the first episode of her Caribbean Travelogue: Haiti.

Tony Capellan (1955-2017) Mar Caribe, 1996.

Caribbean travelogue I

AYITI

In November last year I started travelling in the Caribbean region, researching the sustainability of contemporary art practices and the influence of international (exchange) projects, funding, markets and politics. During my research I will be keeping a travelogue for Africanah. My first stop in the region is Ayiti (Haiti), one of the islands in the region I have not spent any time before. For that reason, it’s a place I particularly look forward to, as well as knowing how rich in art and culture it has always been–and, I soon discover, still is.

Nuit Blanche, place Jeremie, with Fastforward & DJ Pat (photo: Mackenson Saint-Félix (first edition)

Nuit Blanche team making arrangements with Andre Eugene (Atis

Rezistance/Ghetto Bienale) for a collaboration during Nuit Blanche (left

to rigth: Raiden, Eugene, Henry, Giscard.

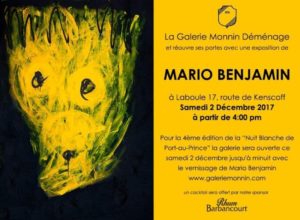

I am hosted by independent curator/producer Giscard Bouchotte. Bouchotte is also the founder and producer for Nuit Blanche Port-au-Prince (1) (now in its 4th year). I am this year’s invited international curator, an excellent introduction to the art scene as a lot of artists and organizations are involved in the occasion. Nuit Blanche is a free event to guarantee exposure to the arts for all the citizens of Port-au-Prince. Bouchotte is putting a lot of effort in making it a sustainable annual project not dependent on (foreign) grants. He prefers to produce it as a joint effort, not only by artists and arts organizations, but the creative industry at large, including graphic designers, print companies, frame shops, media, local transport, publicity companies, and rental houses for equipment, etc. The benefit for all participants is the opportunity to present and brand themselves, showcasing what is available and possible in Ayiti.

The current contemporary art scene is small but vibrant. There are a handful of local galleries such as Les Ateliers Jerome and Villa Kalewes, art dealers (most notably to date Reynald Lally), institutes like Centre d’Art, FOKAL and Institute Français, a few cultural producers and curators like Bouchotte and professional artists including (but not exclusively) Mario Benjamin, Jean Herard Celeur, Maksaens Denis, Guyodo (Franz Joseph), Eugene Andre, Jean Remy Eddy and the relative new kid on the block Tessa Mars, who all exhibit both locally and internationally.

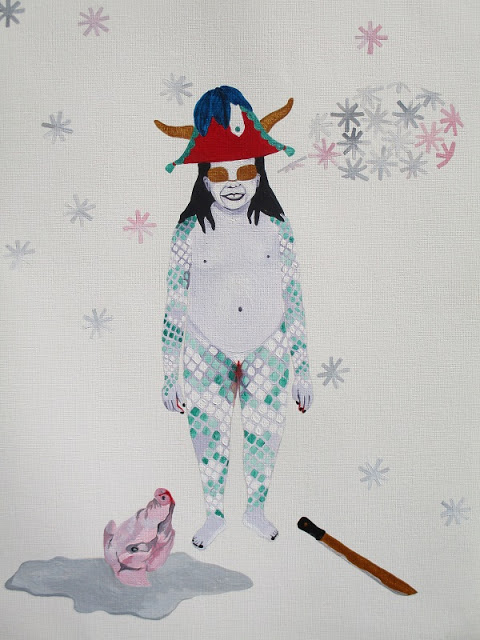

“I start with a formal sketch, I deconstruct it until it is destroyed … and then it appears … within the light.” Mario Benjamin (Port-au-Prince, 1964)

Benjamin represents Haiti in numerous prestigious biennials, including Johannesburg, Dakar, Havana, São Paulo and Venice. Apart from temporary journeys and residencies, Benjamin lives and works continuously in Haiti. As a teenager, he went for summer vacations in New York with family where he spent most of his time in museums and galleries. Since the beginning of his career he has been working abroad for a period every year, either for an exhibition or in a residency. This is the way all contemporary artists get fed intellectually—by conversations with colleagues, to get inspired, and to maintain the necessary contact with the fast-forgetting international art world. Using video and multimedia, painting, installation and other mixed media, Benjamin questions the biased ideas about Haitian artists and art. His paintings have a strong dynamic use of color and powerful almost uncontrolled brush strokes. The work is intriguing, magical but also very dark and intense. You are attracted by the works but they also take you aback. What goes on in the soul and heart of this artist? Benjamin suffers from manic depression and where many artists need drugs to come to certain insights, Benjamin says he comes to those new insights when he has his episodes. Benjamin opened his latest solo exhibition in Gallery Monnin Laboule during Nuit Blanche.

Mario Benjamin (2017),

Bouchotte comes up with an overall theme for the evening, curates an exhibition himself (in a location or site specific) and produces the framing of the overall evening. Bouchotte and his team also are responsible for all the marketing and publicity including a one-page handout as well as a limited brochure of the program with more extended information on the activities and participants. The locations produce and facilitate their own activities within this larger frame. Bouchotte furthermore has a pool of volunteers recognizable in their “Nuit Blanche t-shirts” helping out in all locations to welcome the public, give information on the overall program and help out the locations with extra work.

Organizing the event proves to be a challenge. The decades of lack of financial transparency (this includes the foreign NGOs) continue to feed into a constant continuous distrust by now engrained in everybody in the field. Oral agreements instead of written and signed contracts or minutes of meetings result in last minute frustration and misunderstandings. Being involved in organizing the event exposes the lack of leadership and transparency, not necessarily of the individual people who are well-educated, but of the field as a whole. In order to achieve that, an organized unified arts field advocating for its greater interest is needed, as well as an organization that could formulate and communicate the value of the arts within the society. Implementing cultural governance and fiscal regulations (2) to make (arts) organizations and NGOs more transparent to its field as well as with the public could help to gain trust and contribute to leadership. Cultural governance however does require stable governmental departments where at the least the department policy makers’ respect agreements made regardless of the party in power to avoid needless repetition of negotiations to guarantee continuity, structure and support of the field.

Frantz Jacques aka Guyodo, The Elephant (2017), mixed media, Guyodo’s work was part of the group exhibition curated by Bouchotte for Nuit Blanche in Gallery Nader in Petion Ville…

Accountability and keeping the big picture in mind is a reoccurring problem. Artists in pursuit to sustain themselves are in constant conflict with the daily hand-to-mouth reality of the lower and middle class. The international market requires reliable consistent pricing to guarantee the value of works bought by collectors and investors. I notice artists selling out of their studio set their price based on their needs and their judgment of the net worth of the person who is buying (a practice not limited to Ayiti). Pricing presumes to be consistent when you buy works in the different galleries but “the grapevine” tells me otherwise. The gallery prices are also undercut by artists who continue to sell works out of their studios instead of referring interested collectors to their respective gallery. A visible and known lack of accountability by all parties involved keeps a contemporary art scene in any location from serious interest internationally. To participate in the international contemporary art market, any local art scene needs to underwrite the bigger picture and take the international codes and regulations into account.

International museums have occasionally shown interest in outsider art or presenting works from Ayiti in an anthropological or geographical setting. Acquisition or commissioning of art works in Ayiti to date mostly seems to be done within the framing of craft, (ghetto) tourism, aid or social/political projects and statements. Point in case this January right after Trump’s “shitholes” remark, the MOMA put “The Congo Queen” (1946) by Hector Hyppolite, which is part of their collection gifted by Mr. and Mrs. Walter Bareiss on view to the public for the first time. It was never shown before.

Founded in 1944 by a group of local intellectuals and the American DeWitt-Peters (1902-1966) it was Center d’Art that was instrumental in the first ever artwork from Ayiti, René Vincent’s 1940 painting Le combat des coqs, ending up in MOMA (3). The organization supported talented local artists with materials (paint, paper, canvas, brushes) education (workshops, lectures, dialogues) and presenting work. Center d’Art had the attention of international visitors: Andre Breton, Wilfredo Lam and Jean Paul Sartre and others who contributed to the visibility and professionalization of the art scene in Ayiti in that period. It was Breton who wrote about Hector Hyppolite and showed his work outside of Ayiti which started his international career, to date framed as outsider art.

Local artist and founding member of Centre d’Art Lucien Price (1914), considered to be the first Abstract artist from the Caribbean region, rebelled against the commercialization of work by untrained artists to the international market demand for primitive style objects and popular religious imagery. In protest against this practice at Centre d’Art where deWitt Peters, in line with American McCarthy era politics (1947-1956) which considered modern art to be communist-inspired, Lucien Price left in 1950 and co-founded Foyer des Arts Plastiques in opposition.

Centre d’Art was destroyed in the 2010 earthquake. It reopened for its 70th year anniversary in 2014. All of the artists I meet mention the work the center has been doing the past few years since the reopening to help push the arts forward locally and internationally in a positive way. Contemporary artists like Tessa Mars now teach at the Center.

Tessa Mars is a young emerging artist who is finding her own authentic voice. A painter at the start of her career, after a three-month Davidoff Initiative residency in New York, she is now venturing into other media like animation and stop motion. She uses herself and her experiences as well as popular culture around her in her work. During a residency in Alice Yard she created the alter ego Tessalines, a merging of Tessa and Dessalines (Jean Jacques Dessalines was the leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent Haiti under the 1805 constitution). As with many young returning artists in the region, she has the need to be part of a discourse and critical feedback. Mars teaches young artists at Centre d’Art and is actively looking for other professional artists both locally and in the region with whom she can have these critical conversations. She hopes that locally Centre d’Art can be that platform to meet both more experienced artists as well as her own generation in order to grow intellectually, technically and practically in her practice.

Tessa Mars, Tessalines series, Victorious (2015) Acryl on paper, 40,64cm x 30,48cm.

Last October, Center d’Art organized an auction of works through Piasa in Paris. Half the profits went to Centre d’Art which is using that income to continue rebuilding, half to the artist. The catalogue (4) includes the artists’ bios, pictures of works, measurements and prices.

Artists, galleries, art dealers and collectors can use the auction as a benchmark for artists from Ayiti participating in the international market. Yet some of the artists feel it’s a benchmark for what they should get in hand. In negotiating with galleries they want to be paid the amount that was paid by buyers at the auction. In order to function in the international market everybody who works on a sale of the work needs to be paid from that set price. Generally speaking the typical split is artists 50% / gallerist 50% or artists 80% and dealer 20%. Variations are possible depending on the agreements between artists and gallerists/dealers. Artists should take in account conditions such as whether contracts are exclusive or not and for which territories? Also in these times online sales make other arrangements possible as well. Artist also need to be clear in their dealings with galleries and/or art dealers who is paying for what out of their respective percentages (framing, transport, marketing, etc.) and put what is agreed upon in writing. It is important that artists keep informing themselves about the business side of their profession and/or hire people (lawyers, agents) who represent their interests. The auction price at this time can be used as the benchmarked price that the work (and works like it) is valued to date. What I saw happen in November is that artists brought works to galleries to present and sell demanding to be paid the full price of the auction which then leaves the gallerist with no income at all or a work that the gallery can’t sell as the price they then would have to ask is way over the benchmark. Some artists would not give in, and as a result the work was presented but would not be sold/bought.

Regardless of all the challenges, the contemporary art and craft scenes in Ayiti are very inspiring. I admire the resilience, passion and artistic urgency I notice amongst the artists and artisans despite the social political situation in the country and how difficult life and work really is in Ayiti (GDP per capita is $730) (5). Ayiti now has a small but active contemporary art scene that has outgrown exotics and outsider art as well as a growing crafts/artisan field.

Professional artists have been the inspiration and stimulus for the communities of artisans and are influential in the crafts field becoming economically viable for larger groups of residents. The craft districts that have the most attention local and international are in Noailles in the city Kwadèbouke (Croix de Bouquets) and the district Grand Rue in Port-au-Prince.

Georges Liautaud, Goat with two heads (1961), MOMA collection

Noailles is knows for the technique “fer decoupé” that was developed in the 20th century by artist Georges Liautaud. The technique of hammering barrels and then making sculpture with it was then also learned and used by artisans to make affordable, easy-to-sell craft products. The products became very successful and are now not only being sold locally but all over the world. (One of the major contracts the artisans have is with Macy’s and if you pay attention you see this work worldwide as decoration). The influence of artists on the craft community is still felt today as is the influence of contemporary artist Jean Remy Eddy who chairs the association of artisans. Together with entrepreneur Pascal Theard, Eddy was instrumental in rebuilding the district to what it is today. Within the urban planning for the district they included large public works by contemporary artists from Haiti. Eddy regularly invites contemporary artists from the city to visit his workspace which includes a small library and school to work with the local artisan community to inspire the artisans to be innovative in the work they make. New Media artist Maksaens Denis is a regular invited artist. Together with founder Barbara Prézeau-Stephenson, he is also the co-organizer of the Transcultural Forum of Contemporary Art that takes place in Noailles every 2 or 3 years, which has to date featured 7 editions.

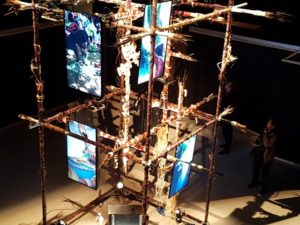

Maksaens Denis is a multi-media artist and interaction designer. His work is socio- politically engaged and rooted in the spiritual life that comes natural to Ayiti. His mom is an internationally-known classical pianist and he grew up with classical music around him all the time. While studying and working in Paris, he worked as a techno DJ and VJ. Both have informed his practice and inspire his scores. The works by Denis are a sensatory experience. He uses performance, sound, visuals and installation. All works reflect the different realities of living in the Caribbean, Europe (France) and Africa (Senegal) and how that has informed him as a human being as well as an artist. In our conversation, he explained how after being in Europe for a long time, living in Africa has completed him. He needed both experiences to understand himself, his identity and how to be at peace as a person and as an artist both in the Caribbean as well as outside.

Maksaens Denis, Untitled (2017), multi-media installation

In Grand Rue (Port-au-Prince), sculptors Eugene Andre, Jean Herard Celeur and Guyodo (Frantz Joseph) founded Atis Rezistans a collective that disbanded in 2010 after the first Ghetto Biennale, a cross cultural arts festival, was organized. The three artists make works from recycled materials as demolition cars, rubber and wood that are being exhibited internationally. After the earthquake, the Atis Rezistans Yard (as of then solely run by Eugene Andre) was turned into a production space for young artisans who are trained by Eugene to produce/manufacture vodou-inspired paintings and sculptures (using the recycled materials) for the ghetto tourism market. As in Naoilles this craft now sustains a growing group of young artisans in Grand Rue. Produced by Andre and his partner artist Leah Gordon (UK), the Ghetto Biennale invites international artists (on their own cost and initiative) known for site-specific work to come and produce work in the Grand Rue area every 2 years for a period of 2 weeks. The media attention generated by the Ghetto Biennale is helping to generate sales for the artisans and other people living on the grounds working as assistants, drivers and translators for the foreign visiting artists.

BACKGROUND TIMELINE AYITI (6):

Ayiti, like other islands in the Caribbean region, BC was populated by Arawak constantly trekking around in the region. Taino (a specific Arawak people) settled down permanently on the island in 600AD and named the island Ayiti (Kiskeya was another name used). Taino are considered the native people of Ayiti which for centuries (600AD till 16th Century) was one country with nowadays Republica Dominicana.

Since the 16th Century the island experienced years of being invaded. First by the Spanish (16th century) who encountered the island in 1492 documented it on their world maps as “La Isla Española”. In the 17th century the Spanish and the French battle over the island for decades. Their settlement in 1697 divided the island in the two parts it still is today. The French occupied the western part of the island that continued to be called Ayiti and the Spanish occupied the eastern part of the island nowadays Republica Dominicana (Quisqueya).

During the 16th and 17th centuries under the occupation by both the Spanish and the French, 450.000 enslaved people from Africa were bought and shipped to the island for unpaid labor on the 800+ sugar and coffee plantations (the majority on the French part). This made the enslaved people from Africa the largest group of the population (7). In 1789 the enslaved people inspired by the French Revolution and the abolition of slavery in the French colonies in 1794 started revolting. Their leader Toussaint Louverture (formerly enslaved) pushed to gain control in 1801 but he was captured by Napoleon in 1803. The revolt continued with Henry Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessalines and they defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Verieres. Dessalines officially announced independence in 1804.

President Jean-Pierre Boyer, decided to invade the Spanish part of the island and reunite the island under the Haitian flag which only lasted for 22 years (9 February 1822 to 27 February 1844). In 1826 Boyer agreed to pay 90 million gold francs (worth US$22 billion today) for diplomatic recognition from France. This debt was only paid off in 1947.

America invaded the island in 1915 which lasted till 1935. In 1957 Francois Duvalier (Papa Doc) was elected president and established a dictatorship. With his death in 1971 he passed his power to his 19-year-old son Jean Claude Duvalier (Baby Doc). During the Cold War (1947 – 1991), Ayiti (the Duvalier family) received large sums of annual “US Aid” as it was strategically relevant to America as a buffer to Cuba and possible expansion of socialism and/or communism. Cuba, socialism and communism were considered a threat to America advocating capitalism and imperialism.

In 1986 the army rebels against Duvalier, forced him to resign and called for a democratic election. Jean Bertrand Aristide became president with 67% of the vote in 1990, only to be overthrown in 1991. US president Bill Clinton reinstated Aristide in power in 1994 and forced him to restructure the economy according to IMF demands, resulting in the collapse of the rice industry. In 2010, an earthquake measuring 7.0 on the Richter scale killed over 250.000 people.

Ayiti today is a democratic country of about 11 million people. Its president is Jovenel Moïse (February 2017 to date). 1% of the citizens owns 50% of the wealth, 80% lives of less than $1 a day.