In November last year Sasha Dees started travelling in the Caribbean region, researching the sustainability of contemporary art practices and the influence of international (exchange) projects, funding, markets and politics. During her research she will be keeping a travelogue for Africanah.org.

In this 6th article the focus is on The Dominican Republic. Her conclusion:

Quality can no longer be determined and judged exclusively by the native European canon. Art and artists in reality have always moved between canons, fluidity is key, curators and critics can only benefit when they fully and without hesitation accept this principle. No canon is set in stone, and no canon has ever been owned exclusively by anybody, so let’s get to work and keep it moving.

Belkis Ramirez, A Cup of Coffee, 2000

Caribbean travelogue 6

Republica Dominicana

My first trip to The Dominican Republic (DR) was in January of this year. I traveled to Santo Domingo, Altos de Chavón School of Art & Design in La Romana and Centro de Leon in Santiago. I did return for Tilting Axis in May and June. Tilting Axis is a conference on Contemporary Art in the Caribbean, composed of curators, writers, critics, scholars, art collectives and others who work with artists from the Caribbean region. It took place in Centro de Leon in Santiago and the Centro Cultural de España in Santo Domingo. In my final weeks after the conference I did visit (and re-visited) more artists and institutions in Santiago and Santo Domingo.

Jorge Pineda, untitled, 2016

During my visit I am instantly confronted with how little I know about the country, let alone its art scene. I am hosted by established artist Jorge Pineda. We met before in New York at a Small Axe event at Columbia University, and I have been following his work for some time. He gracefully invites me to stay with him and introduces me all over town.

For the first three weeks of January, my days start at 9AM, where I am put in a cab with a schedule of names and addresses, and this list keeps me busy into the evening. I meet established peers Belkis Ramirez, Pascal Meccariel, Raquel Paiewonsky (all part of artist collective Quintapata), Quisqueya Henriquez, founder of the artist platform Sindicato, and others. I meet mid-career artists amongst others Elvin Diaz, Fermin Ceballos and Engel Leonard. I meet emerging artists such as Amy Hussain, also founder of Casa Quien, a relatively new gallery/residency space for emerging artists in Zona Colonial and Jorge González Fonseca, who is co-founder (with Ian Victor) and curator of HOY – Santa Bárbara, an urban art festival held in the Colonial is City and of Modafoca, a design and branding company that includes a gallery for urban art exhibitions. In between this brutal schedule, Pineda shows me his library and gives me a stack of books and catalogues to read. Our conversations over breakfast on his gorgeous roof garden and in his studio in the evenings are my introduction to “his” art scene.

Jorge Gonzalez Fonseca

Amy Houssein, Cries, 2016

I realize how dominant the English speaking countries are in ‘my world’ and how the art of ‘his world’ has been totally out of my sight. His art world has its own economy of fairs in Spain and Latin America, collectors, schools, museums and artists that I’ve never heard of. In the new global market, it seems about time to make these connections and I want to include all countries and tongues in my research.

The Dominican Republic country seems to have the handicap of doing relatively well (it’s the strongest growing economy in the Caribbean and of Central America). Photographer Polibio Diaz says during our meeting, “Nobody is interested in us, as no major economic, nature or political disasters are happening.” He has a point, no devastating earthquakes in DR. Trujillo was not threatening to the liberal capitalist world like Castro. The latest political news from the country has been Pulitzer Prize winner and Dominican born Junot Diaz falling off of his pedestal because of #metoo allegations and the issues this country has with refusing and deporting Haitian migrants.The latter being something like the US building their wall on the Mexican border and Europe’s wall between Turkey and Syria, all in an effort to keep the ‘others’ out.

Elvin Diaz, Placenta, performance/video on the border between Haiti and Republica Dominicana, 2016

Between Cuba and Haiti, we have plenty to put our meddling noses in. The Dominican Republic’s art scene falls between the cracks and out of our sight. Diaz checks with me names of artists from Haiti and Cuba he assumes I saw in museums in US and Europe (he is right). He asks me how many Dominican artists I’ve seen in the MoMA, or in any other major museums or exhibitions in the past 10 years, and I am silent. All of the sudden, the world seems not so global at all, but very segregated. Attempts are made. Miami Basel Art Fair gives attention to Latin America and the Caribbean. Museum exhibitions such as Infinite Islands in The Brooklyn Museum, El Museo Del Barrio in New York‘s exhibition Caribbean Crossroads of the World and KADE in Amersfoort’s exhibition Who More Sci-fi than us? have been trying with mixed results and reviews to make connections over the past years. The last acclaimed ‘Caribbean show’, Relational Undercurrents, (2017 and ongoing) curated by Tatiana Flores for the Museum of Latin American Art in Los Angeles and travelling from NYC to Miami, shows over eighty artists in an inclusive representation of the region. It not only has a substantial amount of Spanish speaking artists that include artists as Jorge Pineda and Fermin Ceballos from The Dominican Republic, but the exhibition also includes the even more ignored Dutch speaking countries by presenting artists such as Ellen Spijkstra (Curacao) and Natusha Croes (Aruba). That said, none of these museums or galleries are on the level of MoMA. Also all these initiatives have a geographical focus.

Polibio Diaz,Después de la siesta (After the nap), 2002-05

You have to wonder where are the shows that are just ‘random exhibitions’ in established museums and galleries where artists from the region are selected on the basis of their work and universal themes not because of their geographical location or based on regional issues. Why do curators and critics always expect non-European artists to make geographical cultural statements about their work? Why don’t we expect or ask the same from British, French, German, American or Dutch artists? Why is it that residencies that welcome non-European artists often ask them to explain in their applications how their work is related to their local culture? Why don’t we validate artistic urgency, allowing artists to themselves in the investigation of concept, form and esthetics?

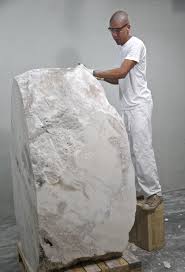

Fermin Ceballos, Acción Para Buonarroti (Action to Buonarroti), Performance 16 day’s length.

In his latest work Pineda makes all the figurines faceless and without visible skin. He refuses to make a statement about gender, sexuality or race, instead placing his work in the universal. This seems a strategy to navigate the curator’s and critic’s attempt to diminish his work as a localized instead of from personal and intellectual inquiry.

For Europeans, the whole world is ours without any explanation. We own it. Our creativity and ideas are limitless. We can forever be innovative. We are allowed to talk about everybody and everything without sanctions. Europeans seem to have this everlasting craving for exotics and tropical escapism while at the same time keeping these places at an impersonal distance. Recently, artists of European descent are being questioned by non-European art professionals when making work that includes black bodies. Yet European curators, critics and even colleagues have always questioned Black artists as to why they paint or portray white bodies in their work.

Ultimately, native Europeans continue to question the quality and legitimacy of work by non-European artists and art professionals. I question such precedents in a changing Europe in an earlier essay, “Don’t Believe the Hype” (published in BAT, Bridging Art + Text, 2017 edited by Michelle Eistrup and distributed by Hurricane).

Jorge Pineda, pesa, 2016

All over the world artists are making contemporary, conceptual art. Sometimes that works does reflect their cultural geographical location and sometimes it tells absolutely nothing about their surroundings or culture. When and why was it decided that this latter kind of work is only possible when you are a native European artist? Europeans don’t own contemporary, abstract or conceptual art, and we are not the only originators. One visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art alone should already cure you of such assumptions.

As curators, critics and writers in Europe, we sometimes are pretty lazy and protective of our positions. We go with what we know because why would we go out of our way to do any research or give space for other perspectives? It’s a sign of the times, like the disappearance of investigative journalism and social media becoming our main source of information. We need to safe-guard the art institutions and funders that maintain the research arm of curating, as well as the wondering, the time-consuming, and the excitement of finding new works to offer our institutional audiences new perspectives. It is our job to spark curiosity. It is not our job to present the art audience with answers, but with impulses, by keeping their minds open and instigating questions and dialogues to expand their imagination. We should leave the audience in awe from aesthetic and formal encounters.

If in our job as curators and critics we want to be part of an expanded discourse, it is necessary to either understand all spaces or make way in our institutions for colleagues that have that expertise. It is not the responsibility of artists to explain their spaces to us, nor to make work that caters to our understanding.

Obviously one of the major problems in the US and Europe is the fact that we have not been really interested in other spaces. We only want to own them. This is now biting us in the ass. We are responsible to do the work solving problems that have now come to our own turf. We might want to take the backseat for a while and research with due effort, with an open mind, observe and be willing to adapt our gaze and frames of reference. We have to stop expecting others to do all the work for us and just give us the answers in short bullet point presentations.

Engel Leonardo, Planchas part of Ranchos, Planchas y Gallinas, 2016, Venezuelan Pavillion, Santo Domingo, 2017

Quality can no longer be determined and judged exclusively by the native European canon. Art and artists in reality have always moved between canons, fluidity is key, curators and critics can only benefit when they fully and without hesitation accept this principle. No canon is set in stone, and no canon has ever been owned exclusively by anybody, so let’s get to work and keep it moving.