For his work Gravitas the African American artist Hank Willis Thomas used a photo of South African photographer Graeme Williams. He turned the orginal work into a black and white photo highlighting the image of the children outside the context of the militairy patrol on the bus in the original photo. Williams got furious and called Thomas a thief, Thomas called for reflection but, in the end, removed the work from the fair where it was presented. Stealing or appropriating? A crime or just a commentary?

Athi Mongezeleli Joja brings light to the case.

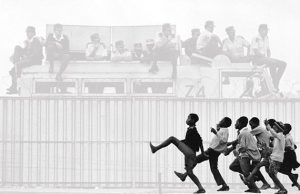

Hank Willis Thomas, Gravitas, 2018

Challenging Appropriation via Scapegoating

Hank Willis Thomas v. Graeme Williams

The accusations of theft made against African-American photo-conceptual artist Hank Willis Thomas calls for reflection. Williams accused Thomas of “stealing” his famous 1990s photograph showing black kids taunting a group of apartheid policemen, and used it in his photograph Gravitas, displayed at the Goodman Gallery stand at the 2018 Joburg Art Fair. Williams was quick to alert the public of this “crime”, and in no time, the issue had made international news where it’s also emerged that Thomas “stole” works from eminent black photographers such as Ernst Cole and Peter Magubane.

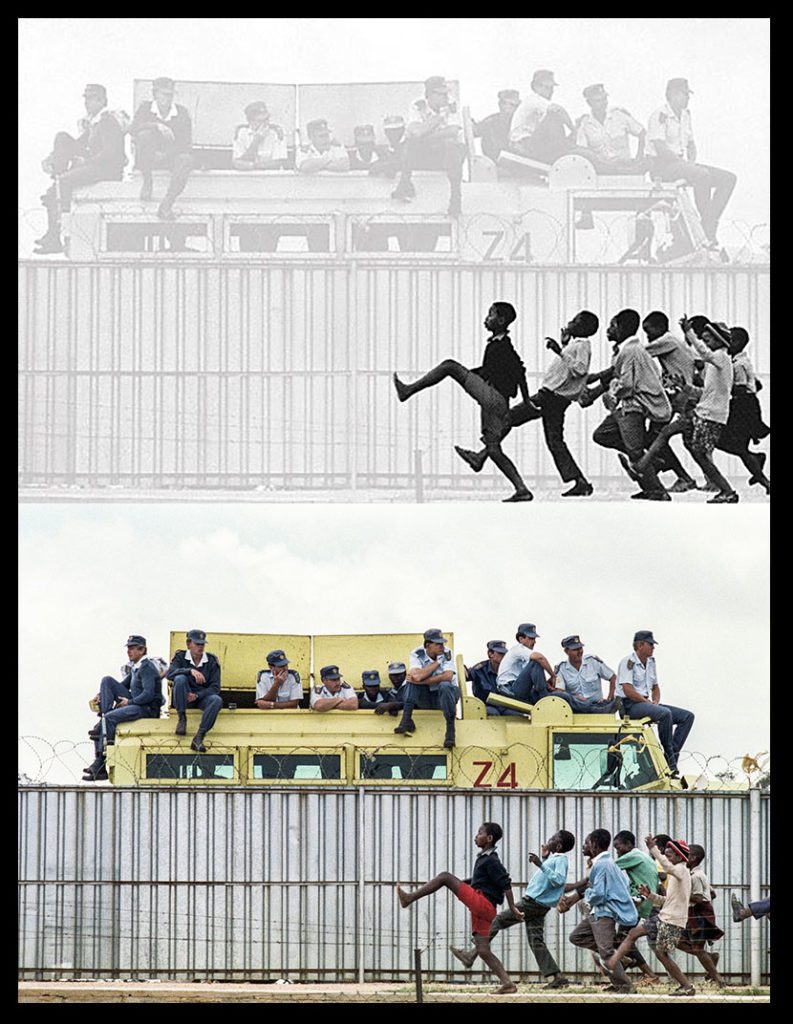

The combination of the two photos as published on ArtNetNews, above Gravitas (2018) of Thomas, at the bottom the original photo of Graeme Williams, 1990.

That I only come to party so late in the day, way after the storms have passed and the scandalous “take downs” have reduced to a gentle simmer is deliberate on my part. I had rather enthusiastically followed the discussions (locally and abroad) close enough to have an idea of the charges raised so fervently against Thomas. I must say, of my own reaction to the photographs at the Fair; I was a little apprehensive by their overfamiliarity. That being said, I did not anticipate the kind of backlash that would later ensue, let alone the slew of problematic turns to be made by the various interlocutors in the debate. Reading local writings, the contemptuous dismissals escalated from moral imperative to a full patriotic blast against “foreign invasion.” It was in the back to back, and, at times, even tag-team critical efforts of photojournalist Greg Marinovich and U.S. based professor of English Neelika Jayawardane, however, that left me rather discombobulated. It was unclear to me if Thomas’ actual crime, or rather the case lodged against him was that of theft because he used a photograph that wasn’t his or that he used it and never gave due credit to the owner? Or was it both? In rather overlapping streams of reportage, the primary charge lingered between the above as it also suggested something beyond. However, the centrality of the accusatory appellation (thief), appears to be the objective behind Thomas’ evisceration and the indirectly implied likening of him to a colonialist.

Now, before really thinking about the merits and demerits of this accusation, I was struck by the methodical scaffoldings, conceptual conflations, and the political interests that permeated these writings. Of course, there’s always been a problem of truly distinguishing between appropriation in art, and appropriation as a historical act of imperial dispossession — not that the distinction is a neat one or one of mutually exclusive categories. Far from it! Appropriation as an imperial ideology has all the distinctive features of colonial subjection, whose unfolding in the historical stage has not only created Euro-American racial dynasties but hitherto sustains them by repeated acts of dispossession of corporeal, intellectual, and labouring capital of the oppressed. Dispossession is thus enunciative of a set of founding proprietary logics. It is the primal “crime” scene generative of all other forms of appropriative undertakings including its laws, aesthetics, and morals. In the South African Constitution for example, “private property” is a metonymic sign of conquest, under the fictitious view that it is a general good.

Graeme Williams made this photo at the Joburg Art Fair, 2018.

In art, there are historically interesting detours and strategies artists have used to question certain aesthetic categories, and societal value systems. At face value these digressions are not immediately reducible to appropriation qua coloniality. Although appropriation in art historical discourse is periodically attributed to the late 1970s largely photographic works by white women artists like Sherrie Levine, Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger et al. its antecedents stretch back into the opening years of the 20th century. As an art critical inquiry, appropriation aimed at undermining basic art categories such as authorship, originality, property, value, low/high art, and so on. That is, it put into crisis notions of auteurism; interrogated the art object’s relation to ideology; echoed marxist decrees of anti-property; enabled feminist postures like that of Levine’s for “stealing” Walker Evans’ photographs, and so on. Developing in conjunction with major theoretical, and political “break throughs,” it brought with it a new vocabulary, that redirected artistic practice and theorizing. Though “stealing” contradicted copyright laws and landed major artists in legal hot waters, within art discourse, thieving implied a notorious, albeit critical, posture that has come to inform an array of assumptions prevailing today. However, for some art historians and critics, the same discursive interventions never truly contradicted the structural defaults of capitalist relations, instead they were subsumed and re-commodified into what John Berger calls “the ritual object of property.” Appropriation art turns into a “property” of culture, therefore of copyright law, whilst the law in its very founding was percolated through, and remains permeated by what Frank B. Wilderson terms “the grammars and ghosts” of slavery, and its afterlives. Though in this position, the point isn’t to undermine appropriation in art and perhaps the “necessity” of its legal counterpart, but to glibly show how both abet and are pervaded by the crime scene of the colonial encounter.

Graeme Williams (2012), photographer unknown.

So back to Williams — his colour picture shows a group of black boys comically play-acting out something between a toyi-toyi and an army drill, in front of apartheid policemen hunching atop an armored vehicle. The cops are looking out into the horizon (out of the frame), over the barbed wire fence, ignoring the taunting happening below. The humor and seriousness captured here arguably instantiated the performative “gestures” — in Okwui Enwezor’s sense — that elaborate atmospheric tensions between defiance and discipline. For his part Thomas decolours the image into a black and white rendition, white washing the backdrop into relative opacity without erasing it, whilst sharpening the contrast on the foreground as if giving a shadowy prominence to the boys. The alterations seem much more obvious and deliberate, if not altogether parodic and signifying. And if read within a certain purview, it generates a number of curiosities pertaining both to photography as a reproductive practice and the conceptual choices that might undergird the gesture of shadowy prominence.

Determining whether Thomas’ rendition of Williams’ work is “successful” or not seems equally pivotal to the discussions on the matter. The argument overwhelmingly is leaning on the fact that it has drably failed to re-render it and thus qualifies as straightforward thievery. Mind you this judgement has cared less to read Thomas’ photograph on its term, owing perhaps to the fact that it was rejected or had no basis from the onset, its juridical interventions seems slightly prejudicial. Retrospectively reflecting on the matter, Thomas after all “never had any intension of claiming attribution of Mr Williams’ photograph: I was 15 years old when it was taken and living in another country. My work is intended as a commentary on the original image, and the nature of photography itself.” Well, “intention” here could easily be a euphemism, just to politely appeal to the sensibilities of Williams and his avengers.

This follows after his own remarks about how appropriation has been an obsession “within the field since its beginnings.” Its not clear which “field”, and which “beginnings,” but we will be remiss to not fill in the gaps ourselves. Without taking a breath, Jayawardene weighs in to “correct here” that questions about representation and appropriation have not, in fact, been raised “within the field since its beginnings.” Instead, she argues citing “a friend” that these things have been raised more recently by “critical race theorists, critical feminist, and critical queer theorists.”And citing from Jayawardene’s article, his friend, Marinovich, chimes in contradictorily and says “Indeed, they have, but not in any way to support what he has done, and is doing in appropriating/stealing/borrowing with permission.” Interesting!

Hank Willis Thomas, photographer unknown

Thinking about the anonymous beginnings, and the shoddy reference to a recentness, in conjunction with the art historical context briefly proffered above, there is a shared proclivity towards obscurity, and dehistoricism that cuts unevenly on all sides. Following the corrective, Jayawardene stresses, almost in contrast to the art historical tendency, that we heed the wayward ways of Thomas’ “simple appropriation”, and therefore equally of “clear ownership and lineage.” The jargon used throughout the writings that contest Thomas’ work are legalistic, and seemingly at odds with the explanatory fantasies of “the field.” I, however, am neither invested in whether Thomas’ photographs are uncourteous or not to Williams, nor whether or not former President Obama was moved by it. I am, instead, interested more in its curious and selective moves employed in pursuit of exposing Thomas’ thievery. That is, how, for example, this discussion prioritized a legal framework on one side and on the other operated in a kind of art historical tabula rasa. Meaning how the convictive precedence of the law (thief) was invoked without the slightest inclination to give his work an art historical backdrop. The law, it seems, contains a much needed public punitive measure, whilst “the field” seems conducive to a complication or even opposition to the case, and therefore must be suspended. This double denial has all the hallmarks of a productive and ominous tension, which can be both concealing and revealing.

Things get much clearer as to what truly subtends the matter, i.e. not only by their continual mutual referencing, but when Jayawardene and Marinovich enter into a collaborative duo in an extended, albeit repetitive, article published in the Mail and Guardian. It must be said from the outset that photographers like Marinovich and Williams gained their prominence by largely taking images of black townships during the “transition” because those were the kinds of images the international communities wanted to see. Blacks embroiled in grotesque and violent encounters, poverty stricken realities of postcolonial African subjects, and the entertaining spectacle of protest from which various corporations and media outlets depended on for extractive posterity. In his article In Rise and Fall of Apartheid, Enwezor discusses this, drawing particular attention to the Bang Bang Club, that they “were hired guns in the midst of the mediatization of conflict and the orgy of gore…full-on frontality. Rather than nuanced, composed framing of resistance, Marinovich et al. depict struggle as a scene of chaotic, entropic space: violent conflict between warring factions steeped in action and saturated colors.” In the same volume, curator Khwezi Gule picks up on the matter, albeit reluctantly, pointing rather to the subsequent film on the group inspired by a book Bang Bang Club by Marinovich and Joao Silva. Gule writes, “it is clear that the filmmaker chose to mythologize the photographers in such a manner that the story of victims of the political take a back seat to the story of the photographers.” These two citations could tells us a few things about the capaciousness of the term appropriation, more so how these elaborated instances function within a repertory strategy and within a psychic economy parasitic to a certain kind of appearance of black bodies in public visual discourse. But Thomas’ interlocutors couldn’t bring this in conversation with their agenda because like their choice to suspend the art historical narrative in which they are careful to not situate their opponent in, it would complicate matters. The objective is that Thomas must be seen in broad daylight as “the thief” that he is.

The photograph by Graeme Williams taken in Thokoza township, Johannesburg, in 1991. Police watch an ANC rally while children taunt them

It is no wonder that Marinovich opens his dialogue with Jayawardene by declaring the historical status and privilege of both him and Williams within the apartheid geopolitical order. “We were legally and culturally denoted as white in the sacred racial roll call of apartheid. We lived as white people and enjoyed the benefits” he says but also continues, that they used their “cameras to contest the idea of white supremacy.” This is important precisely because it draws into the perpetual narcissism of whiteness, its generic steadfastness in fully enjoying and contesting whiteness in one and the same move. What remains strange however, is how in her introductory remarks Prof. Jayawardene starts by acknowledging Thomas’ unintended thieving, and immediately after that, raises the historical issue of how “our cultural, scientific, intellectual and artistic heritage has been erased, stolen and represented as the inventions of our colonial masters.” To what end? Who is this collective “our” so earnestly invoked against which “colonial master” threatening to once again pillage and loot “our” stuff? It is when questioning the “marginality” of Thomas and his “disingenuous” analogical claims to global and existential blackness, and its cultural improvisatory aptitudes that further, for Jayawardene shows how the US star artist is further interdicted. Not only from claiming “fair use” of Williams’ picture but of even claiming black cultural archival histories. After all, “Thomas’ formal education includes a BA in photography and Africana studies, an MA in Visual Criticism, an MFA in the visual arts in photography, a couple of honorary doctorates and a slew of well-deserved, prestigious awards.” Is it correct to assume here that bringing Thomas’ resume serves not only cast him out of black cultural heritage of Hip-Hop (sampling and remixing) which he rightly cites as influential to his work, but to also tacitly reconstruct him as a “colonial master” out to dispossess Williams? For Jayawardene and Marinovich, Thomas, it seems, does not fit the image of abject blackness to cite remixing and sampling by virtue of his success. Would this not though contradict one of Jayawardene’s own stated remarks in Al Jezeera about how Africans (read blacks) always appear under the stereotypical emblem of abjection in global mainstream media? Isn’t this also the critical position that pervades Thomas’ work, in relation to how blackness is used and abused in advertising media as a kind of trope of ultimate difference? Can we say the same about Williams and Marinovich? We certainly don’t see this in the elaborated journalistic interventions of Jayawardene, seemingly hellbent to provide critical sanctuary for the white photographer and burn Thomas at the stake

From the series: Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915–2015. Copyright the artist. Courtesy Jack Shainman Gallery and the artist, New York

Graeme Williams, Bophutatswana Homeland Garankuwa, 1990 (A factory is set alight during demonstrations against the Bophutatswana government in Garankuwa. Copyright the artist.

My point here hasn’t necessarily been to argue that Thomas didn’t “steal” the work of Williams or, for that matter, Alf Khumalo and Peter Magubane — two figures whose names have been vicariously invoked through and for Williams. But I also understand that what appears as Thomas’ reluctant embrace of this description as a thief, is that he is not Levine, and therefore the symbolic ramifications are not same. If for Levine the moniker thief stood for a kind of critical notoriety, one supposes for Thomas it bears weight that exceeds discursive plains and enters into a realm that repeats all the cruelties of racist stereotypes. So I was interested in shining the spotlight on how whiteness, and anti-blackness for that matter, is consistent in its covering-up of its own criminality and culpability, or how it quickly notices and prohibits any signal of a reparatory inclination. This is a habit in South African cultural practice. And most importantly, Thomas’ gesture invites us to think through vestiges of appropriation not simply as a discursive or legal historical imperative but as a systematic, and even constitutive basis of the current anti-black racist order. Thinking precisely that “property” isn’t only a haunting mode of self-articulation and reenactment but is identically the precise name of the racist order that both Marinovich and Williams have benefitted from and continue to do so under the various Tarzanist caps they wear.