The first contemporary African artist to be exhibited at the Musée du Louvre : Chéri Samba, in the exhibition “A Brief History of the Future”, 24.09.2015 – 04.01.2016

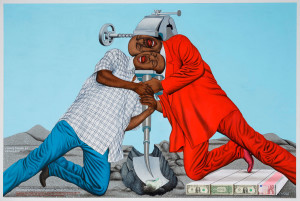

L’Employeur et l’employé, 2013

About the exhibition:

This exhibition—one of the most anticipated at the Louvre in 2015—is based on the book by Jacques Attali of the same name (Une brève histoire de l’avenir), published in 2006. Pluridisciplinary, it brings a number of contemporary artists into a dialogue with noteworthy works from different eras, retracing in the present an account of the past conducive to a clearer view of the future.

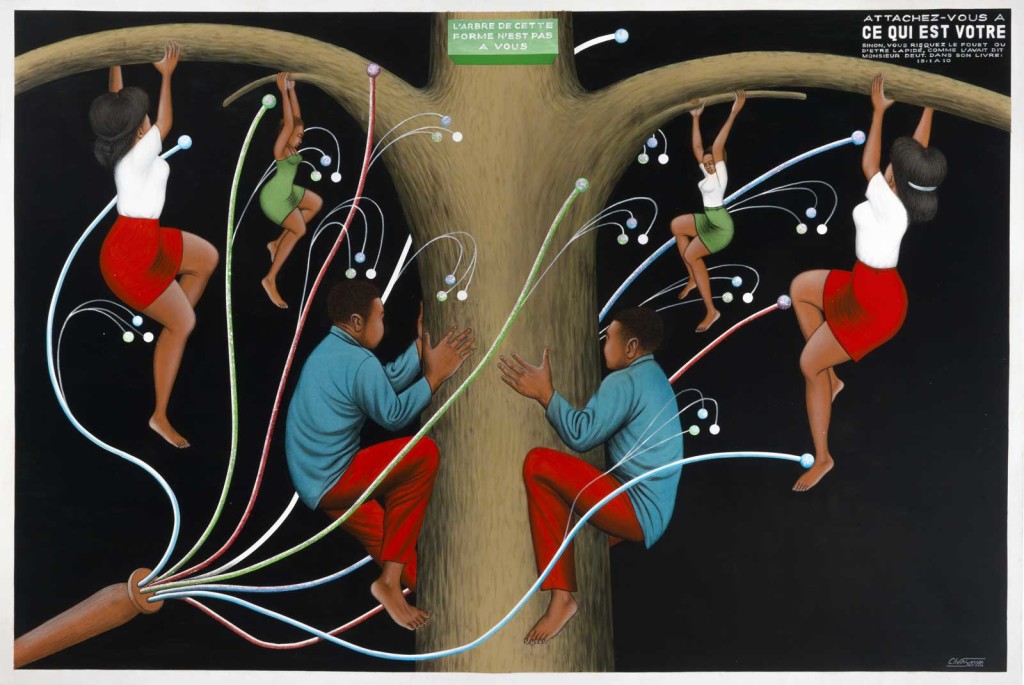

Attachez-vous-à-ce-qui-est-votre, 2014.

The viewing itinerary is organized around four themes, each featuring works commissioned from contemporary artists: the ordering of the world, the great empires, the expansion of the world, and the polycentric world we live in today. Mark Manders, Tomás Saraceno, Wael Shawky, Camille Henrot, Isabelle Cornaro, Chéri Samba, and Ai Wei Wei have thus accepted the Louvre’s invitation.

These artworks highlight the succession of historical moments of expansion and withdrawal, the building of exchanges between individuals or communities, and the creation of various means of communication to make them possible. Special focus is placed on interpreting the artworks and putting them into perspective, particularly through a discussion area created in the last room.(text Louvre)

La météo, 2015.

About the artist:

In 1972 Chéri Samba left school in order to become a sign painter on Kasa Vubu Avenue in Kinshasa. From this circle of artists (which included Moke, Bodo, and later Samba’s younger brother Cheik Ledy) arose one of the most vibrant schools of popular painting of the twentieth century. Working both as a billboard painter and a comic strip artist, Samba employed the conventions of both genres when he began making paintings on sacking cloth (canvas being too expensive) in 1975. Indeed, he borrowed the bubbles from the comics in order to incorporate in his paintings not only narrative but also comments. Samba has recalled how he came to use text in these paintings: “I had noticed that people in the street would walk by my paintings, glance at them and keep going. I thought that if I added a bit of text, people would have to stop and take time to read, to get more into the painting and admire it. That’s what I called the ‘Samba signature.’ Since then I put text in all my paintings.”

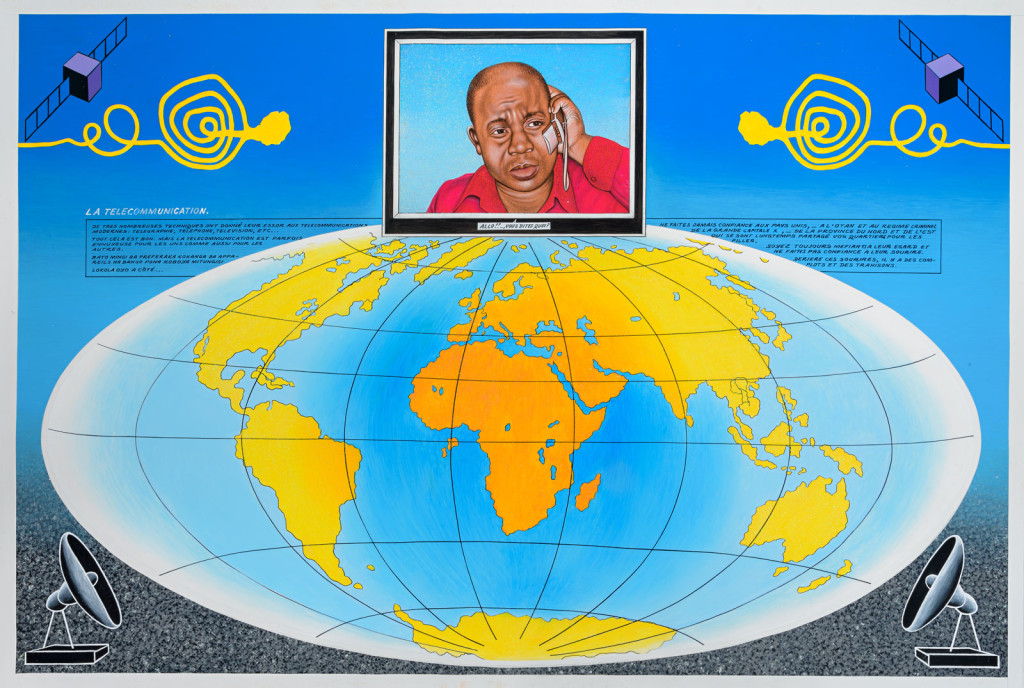

La télécommunication, 2015.

In the early 1980s he began signing his paintings “Chéri Samba: Artiste Populaire.” Indeed, the popularity of his paintings soon went beyond Kinshasa’s borders. By the mid 1980s his work was gaining an international audience.

Samba’s paintings of this period reveal his perception of the social, political, economic and cultural realities of Zaïre (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), with subject such as everyday life in Kinshasa, customs, sexuality, AIDS, social inequalities, and corruption. Samba explained, “My painting is concerned with people’s lives. I’m not interested in myths or beliefs. That’s not my goal. I want to change our mentality that keeps us isolated from the world. I appeal to people’s consciences. Artists must make people think.” Since the late 1980s on, he became the main subject of his paintings. For Samba, this is not an act of narcissism but the narrative of a successful African artist in the art world.(text and courtesy Magnin-A)