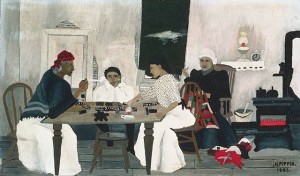

This work – The Domino Players, 1943 – is part of the Philips Collection.

First published: December 2014

About:

(This review of Holland Cotter was published in the New York Times, February 3, 1995)

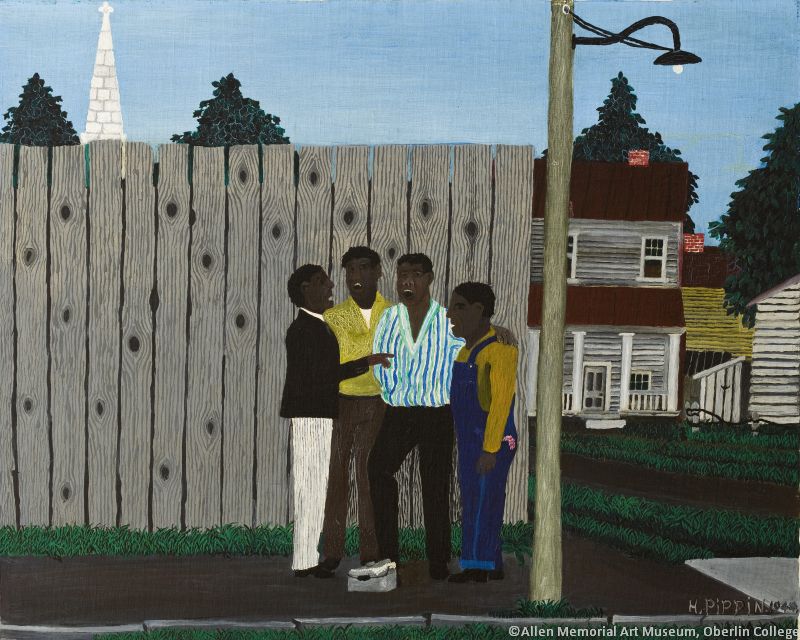

THE quickest route to “I Tell My Heart: The Art of Horace Pippin” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is through the Michael C. Rockefeller wing, where you’ll pass a West African sculpture of two musicians leaning together and smiling as they play. About halfway through the Pippin show itself, you’ll find “Harmonizing” (1944), a painting of four young black men singing, shoulder to shoulder, on a street corner in the artist’s hometown, West Chester, Pa.

The connections between African art and American primitive art (to use a term routinely applied to Pippin’s work) are complex, but one thing is certain. Both are relatively recent arrivals to the world of fine-art museums, and their status still feels uneasy. Tribal art contends with exoticism, primitive art with unthinking affection. We come to it to be tickled and charmed, not to be challenged.

Country Doctor, 1935.

Country Doctor, 1935.

Yet anyone looking to Horace Pippin (1888-1946) only for easy reassurances should look elsewhere. There is much delight to be found here, in his astutely observed vignettes of lives past and present and in the dense, vivid fabric he has woven of religion, historical myth and popular culture. But along with the sweetness, there is often an undercurrent of bitterness, as tart and astringent as a splash of vinegar.

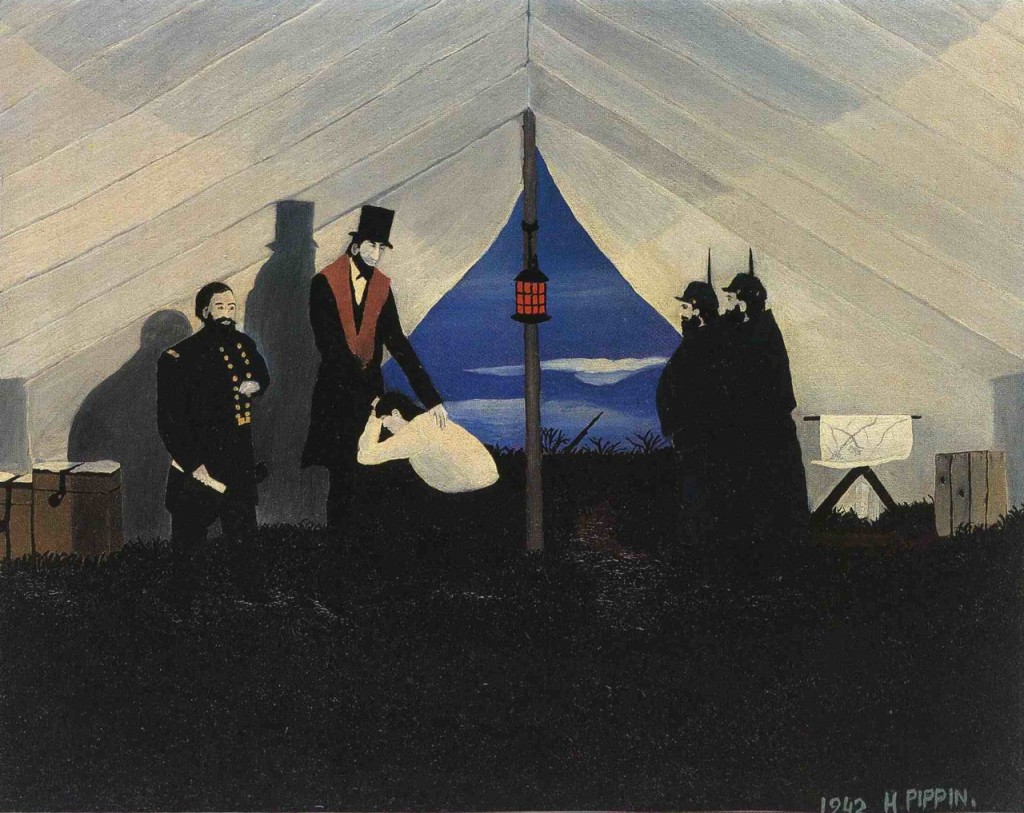

Abe Lincoln, The Great Emancipator, 1942.

Abe Lincoln, The Great Emancipator, 1942.

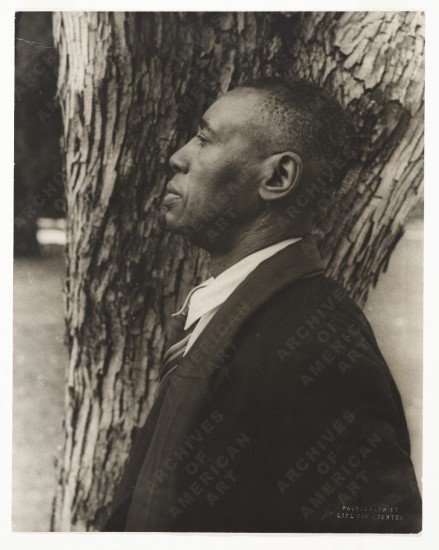

Pippin was descended from slaves. Born into a family of laborers and domestic servants in Pennsylvania, he worked as a laborer himself before entering the Army in World War I. There he was a proud member of the famed all-black 369th Infantry in France until a sniper’s bullet took him out of action, leaving his right arm partly paralyzed. He claimed that he started painting as a form of physical therapy, supporting one hand with the other when using a brush.

He worked with this handicap all his life, and possibly it encouraged the minute attention to detail we see in his work, where each blade of grass in a landscape or thread in a tabletop doily is meticulously limned. At the same time, such literalism, suggesting a hunger for the physical and the concrete, was very much in the American grain, and when Pippin states that his intention was to paint life “exactly as I see it,” we hear a representative American artist speaking.

Pippin’s realism applies to every subject. In a portrait of his wife, he carefully magnifies her eyes behind her glasses. In a mountain landscape, the shadows of trees are carefully painted to look opaque rather than solid black. The flowers in his still lifes are identifiable by name, the soldiers in his war scenes by rank, and the fur of the various beasts in his depiction of the biblical Peaceable Kingdom is distinctively rendered.

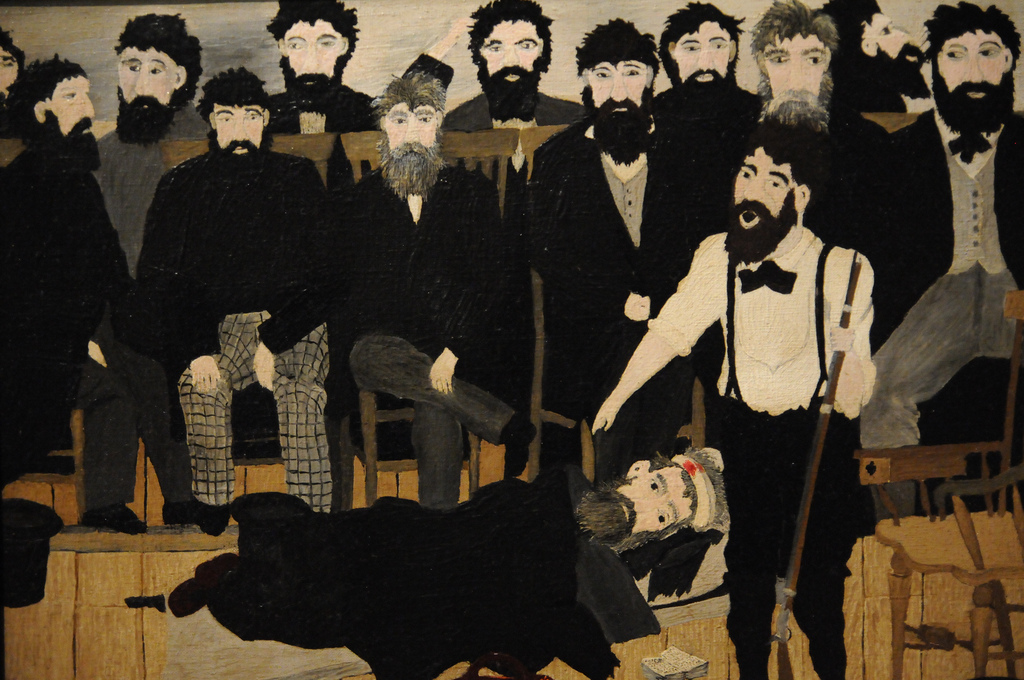

The Trial of John Brown.

The Trial of John Brown.

John Brown Going to his Hanging, 1942.

John Brown Going to his Hanging, 1942.

Nowhere in the exhibition (which was organized originally, in a somewhat larger form, by the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts) is this self-conscious accuracy as moving as in Pippin’s paintings of his childhood. The warmth of familial affection glows in scenes of Saturday night baths and of children saying bedtime prayers by the light of a kerosene lamp. And works like “Domino Players” (1943), with its generations of women quilting, smoking and talking by a companionable wood stove, bring a seldom-recorded existence vividly to life.

Yet there are disquieting things here. Window shades are torn and plaster has fallen from the wall, letting the lath show through. Women and children are present, but rarely men. In a series of exterior scenes titled “Cabin in the Cotton” (1944), Pippin painted fields of cotton stretching to the sky and ready for picking, with the white bolls rendered individually in thick relief, as if to suggest their overwhelming, suffocating presence.

Elsewhere, Pippin makes his sense of disturbance explicit. It is there in “Mr. Prejudice” (1943), a concerned citizen’s plea for racial harmony that is also a disquieting catalogue of the forms racism can take. And it is there again in his remarkable illustrations of the life of the abolitionist John Brown. To the side of the gawking, faceless mob in “John Brown Going to His Hanging” (1942), Pippin places the figure of an elderly black woman, who turns her back to the event and looks straight out of the picture, grimacing as if in anger and grief.

Supper Time, 1940.

Supper Time, 1940.

Even the religious paintings titled “The Holy Mountain,” done toward the end of Pippin’s life, are clouded. They are based on a text from Isaiah prophesying a state of universal peace, where all creatures will live in harmony “and a little child shall lead them.” Pippin’s foreground tableau of a youthful shepherd and his menagerie couldn’t be more benign, but through the forest one catches glimpses of a graveyard of military crosses and a body hanging from a tree.

Pippin was lucky in his career. Although he didn’t start using oil paint until he was 40, he was quickly discovered and promoted. Carried along on the folk-art craze that seized America in the World War II years, he gained considerable exposure, far more in fact than many academically trained artists of the day. His “Cabin in the Cotton” paintings were commissioned by Vogue to be used as illustrations; he had solo museum exhibitions outside of New York City, and his work appeared at the Museum of Modern Art in a group show titled “Masters of Popular Painting.”

At the Metropolitan, the label “popular painting” has been dropped and Pippin is on his own in the wing set aside for 20th-century art, in galleries only recently vacated by Willem de Kooning. All of this is as it should be, for Pippin is not only a powerful artist who can do without categorical qualifications, but he is also, in essential ways, more clearly an antecedent to much current art than is Mr. de Kooning himself.

Harmonizing, 1944.

Harmonizing, 1944.

His detailed recordings of American life find their echo in the work of a wide range of strong artists today, including Faith Ringgold, Pat Ward Williams, Glenn Ligon and David Hammons. The very eclecticism of Pippin’s subject matter — autobiography, history painting, portraiture, politics, religion — has a contemporary ring. And in an age suspicious of heroes, his stature feels about right. Like the West African musicians in the Rockefeller wing, Pippin’s vivid, life-enhancing paintings speak of an immensely rich history in an undemonstrative common voice.