“A lot of people think I go to the streets to sort through garbage for my creative supplies but that’s not what happens. I noticed that people say this, especially in media because they want to use poverty as an overarching theme to rack in audiences.”

Cyrus Kabiru in conversation with Mukanzi Musanga

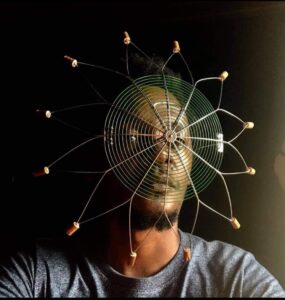

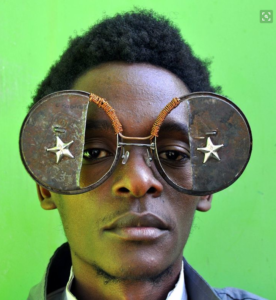

From his C-Stunners Series

CYRUS KABIRU

My creativity is a gift and not from poverty

Cyrus Kabiru is one of Kenya’s most iconic visual artists. The power of his creativity is wielded through a multi-media showcase of intricate artistry. Simply, his art can’t be contained in any singular form and it’s ever shifting

One of his C-Stunners, an ongoing project

His iconic Macho Nne Series or C-Stunners, cast him into the limelight in 2011/2012 and caught a fire that illuminated the rest of his artwork. And yet, simultaneously, it seemed like the world was not ready for the magnificence of Cyrus Kabiru’s artistry. The uniqueness of his work has left many still fumbling with how to describe Kabiru as an artist. They fail to see the obvious- that his artistry defies labels and sprawls freely on a broad creative spectrum. Kabiru is a multi-disciplinary visual artist who employs different media while creating. His creative palette ranges from craftsmanship, designing, painting, sculpting and even filming of his work. He derives pleasure from painting but mostly wields it as a secret charm to unlocking his creativity when it gets elusive.

“I make different types of art from my original ideas. Some people think I’m a designer and I will find myself invited to fashion events. And I show up. I don’t put myself in a box. As an artist, there are no set imitations as to what I should create and so I experiment a lot,” says the soft spoken multi-faceted artist.

From his Bycicle Black Mamba series

While his name orbited the globe and the world marveled at the C Stunners, Cyrus found his story in part, being wrongfully cast. Some foreign media outlets exhibited him as a once-before desperate artist who couldn’t make ends meet. The western media’s ravenous appetite for poverty themes in these kinds of stories from Africa was evident in how they voraciously sensationalized Kabiru’s story as that of rags to riches. They implied that Cyrus pursued art as an escape from poverty- portraying him as a destitute artist scavenging for materials for his mind-blowing art in nasty dumpsites on the streets of Nairobi.

“A lot of people think I go to the streets to sort through garbage for my creative supplies but that’s not what happens. I noticed that people say this, especially in media because they want to use poverty as an overarching theme to rack in audiences,” he says.

A foreign media outlet once asked him to act as if he was rummaging for these materials in a dumpsite for them to film but he declined.

Cyrus repurposes used items into art and he refers to some of these as vintage trashes. He buys them from different local markets and junkyards or gets free deliveries from those who know his work.

From his Bycicle Black Mamba Series

“The products are cheap and I buy some of them from guys who work with metal. So, you can’t actually get them in trash or dumpsites. I get them in markets or junkyards where they are sold,” the artist clarifies.

The implication that art was a conduit out of poverty vexes him as it resides far from the truth. Cyrus does not come from a wealthy background but his parents made sure he never lacked.

The artist posing next to his work

“I try not to let my work get overshadowed by the story of poverty. I started making art as a child even before I understood what the name artist meant. I don’t want to sell poverty. I want to sell creativity. When artists sell poverty, it takes attention away from the brilliance of your work, which should be embraced,” he states. He says “one doesn’t have to run away from their background and story” but they should not permit it to strangle their work. Cyrus says an artist’s work should be purchased out of belief in their abilities. And he understands why an artist may solicit buyers through pity but he sees it as an unsustainable way to market one’s work.

Unfortunately, he says some people seem to be riveted more by the act of buying art to “save an artist from starving”.

Cyrus was coined Msanii, which means creative in Swahili, by his schoolmates when he was a kid. He was popular in primary and high school for his knack for art, which he created for some of his friend’s pro bono, when he wasn’t trading his pieces to get his homework done. Academics alone didn’t do it for him; in fact, he couldn’t stand studying and preferred spending his time making art in a quiet space. He contemplated going to art school but decided against it. With no desire to pursue college education, he decided to focus on art. He even turned down an art scholarship offer in the United Kingdom (UK). His father was not pleased with this. He didn’t see art as a viable career but was willing to pay for art school just to ensure Kabiru gets further education. However, his son was defiant and wanted to create art in his own way.

Cyrus sold an art piece for the first time in high school, to his uncle. At the time, he still had no clue that his talent could be of monetary value. In fact, he felt guilty for selling the artwork to his uncle and resorted to avoiding him. His uncle on the other hand, was also dodging him out of shame for buying the art piece for a low price, feeling that he should have paid more. Uncle and nephew would later on finally have a talk and the former compensated Cyrus adequately.

Studio view

“I was making art from a tender age but I believed an artist was someone who could paint another with their eyes shut. I also never thought I could make money off it,” he recalls.

After high school, he continued selling more of his work which he made in his home studio.

“I didn’t attain good grades in my high school finals and everyone said I would have a difficult life but I remained unfazed. I knew what I was doing. People actually assumed that I was just lazy and didn’t want to work. Life proved me right and my vision manifested itself and suddenly, everyone who doubted me changed their perception of me,” says Kabiru momentarily glancing at a yellow metallic teapot sitting on an old bike in his studio. The kettle or teapot, which he plans to decorate a bicycle artwork with, was a gift from his grandmother who passed away in 2021. They had a special bond. She understood his work and supported him. His grandmother would spare various creating materials for him.

The studio, together with his gallery, are curated from shipping containers. His work station is clattered with heaps of creating media. Asked how he finds his way around and gets everything he needs when making art, he says he just wings it, really.

“But when I have to look for something, any movement from where I’m seated awakens me. And I like the process of sorting through the pile because it spurs creativity when I come across something that I wasn’t planning to use but it turns out to be handy,” he shares. That tends to change the direction of his creativity and even sparks new ideas for projects. But he always ensures that his tools are in plain sight.

When creating on any of his ideas, Cyrus sometimes withholds titling his work to give his audience the chance to interpret it depending on how it resonates with them. “I could give them a story about it but it won’t be what they are seeing and connecting with. I give you a chance to have a conversation with the artwork, perhaps tell me what you see and ask questions. I would like to know what the art means to you or what it brings to mind when you look at it before I indulge you on the story behind it,” he says.

Yellow from a Distance

Then there are those he has named; like the astonishing piece hanging neatly on the wall on his right. Yellow from a Distance is the title and it simply derives its name from the miniature circular dotted yellow spots hinged on it and stand out from afar. The piece is a meticulous gather of an old radio at the core, enclosed with other components such as a bicycle wheel part, wooden cooking spoon, wooden rolling pin and tiny dismantled speaker parts.

More of his artwork, such as his famous C Stunners are named and each has its significance. Some of them carry names of places he has been too such as Ireland and the Vatican. Cyrus travels a lot and, on these expeditions, he collects discarded items from these places and utilizes them to make art. Actually, he started making the eye-wear pieces of varying designs in his childhood.

“When I create, even if it isn’t with the items I collected from my visit, I still do so with the image of that place in mind. For instance, I was in Venice, Italy for a two-month residency and the art I created was drawn from my experiences during my time there,” he says. He started making bicycle art in 2020 and they are quite phenomenal. They have taken on various design forms and none is replicated. He crafts bicycle parts together with other materials to make masterpieces.

From the Radio Series

When he goes to a foreign country, Cyrus doesn’t take his art. To avoid clashing with the Kenya Revenue Authority (KRA) on his return with his art, he prefers to make new art while on a foreign trip.

“When you leave this country with your work, it could become hard to get it back after exhibitions because KRA may confiscate it. There are no clear guidelines governing the tax related factor to art and this makes it hard to get your work back,” he speaks of the conundrum.

This frustration, among others, prompted the formation of Association of Visual Artists and Creatives (AVAC). Cyrus and fellow artists created this organization to secure the integrity of artists’ work and are in the process of registering fellow creatives with a target of having 300 members.

To protect the identity of his work further, Cyrus prefers to model his own pieces. He becomes his own muse, for instance, with the bifocals. Using his face to model the C Stunners is a way to protect his art and intellectual property. In addition, he does it as a way to market his own work.

“I wanted to create that identity where when you see me, you see my work,” he speaks of the strategy.

He is currently making art from old stereos which he says have become attractive to the eye of some of his clients.