His work speaks to the present by utilizing the past and invoking the violence enacted by the church, the military, and even the scientific fields, all under the guise of civilization so as to conquer and plunder black and brown nations.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja on the drawings of Felix Shumba, born in Zimbabwe, living in Johannesburg

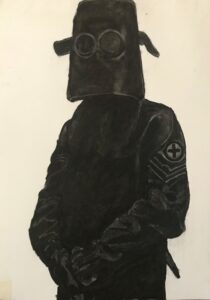

INDX – Non Human, fold, opp. 33, 40, 109, 2020

Felix Shumba: Drawings

I have found myself profoundly captivated by visual artist Felix Shumba’s current charcoal drawings. These drawings shed something quite uncanny in how they play with themes such as violence and masking, or particularly, the contradictory valances of institutional violence and its overall appearances.

Simply put, the logic of the mask operates through the dialectic of concealment and revelation. On the one hand, this means to subdue the subject’s natural disposition while on the other, it also means to act in accordance with the adopted character the mask symbolizes. Shumba’s drawings concern themselves with masking in the wake of Covid-19: that is, how on the one side masking implies a protective shield that prevents the spread of the coronavirus, while at the same time has come to be associable with the return of the authoritarianism of the state through the violence of its law enforcement apparatuses. Of course, masking is a far more complicated concept and stretches beyond these limited alternatives presented here. In all forms, masking implies a possession of the human psyche and body in the name of cultural, religious, political, or even institutional beliefs.

INDX-Gratuitous, Priori 87, 102, 2020

Felix Shumba is a visual artist from Masvingo, Zimbabwe, who currently resides in Johannesburg. Although this piece reflects on his current drawings, Shumba also enthusiastically and skillfully dabbles in poetry, painting, photography, installation-cum-sculptures, and at times performance art. This modest introduction will only focus on his drawings which I have had the pleasure to see and even discuss with him in his studio/apartment in Belleview, Johannesburg.

It must have been around April this year, soon after the national lockdown was imposed, that a couple of videos started circulating, showing either military personnel, the police, or even the newly elected minister of policing reveling in the prospect of arresting and/or even assaulting (and in some instances, fatally) all those who would disobey the regulations of lockdown. An unspoken but nevertheless implied truism latent in these videos was the passionate appetite to harm blacks in particular, who, by colonial and apartheid juridical necessity, have been considered the default criminals and targets of society. And true to form, when lockdown was imposed, the over-presence of law enforcement in black communities not only led to the harassment, abuse, and humiliation of blacks in public spaces and in the interiority of their homes, but also a handful of unaccounted for deaths of black people.

INDX – Necro Polis, Rifle, Roots, 12, 17, 133, 2020

While for South African locals this image is either an intermittent encounter often read in comparison with the apartheid days, as a foreign national Shumba’s experience of the antiblackness of the South African law enforcement is nothing new. It is an ever-present problem that not only resembles the anti-black police brutality of his native Zimbabwe—where the state has been known to frequently unleash the police, and even the military, on its people in order to silence discontent and subdue dissent—but that of colonial Rhodesia and certainly, that of colonial and apartheid South Africa.

Indeed, when lockdown began, and the videos of brutality started to circulate, what Shumba was seeing was a routinized engagement and the afterlife of colonialism manifest. Though the police might not ordinarily wear head-masks, the police uniform itself functions as a kind of disguise—sanctioned rogue personality—which each black cop wears (with pride) to express the assumed infallibility of the state apparatus. Shumba’s drawings are a complementary visual discourse that attempts to invoke iconography of authority through its figures or representatives.

INDX – Alien, Position, Aa, 77, 22, 110, 2020

In these drawings, so far, the artist currently uses, materially, the charcoal and eraser (on Fabriano paper) technique. He constructs dark or silhouetted illustrations of figures whose general visual appearance resemble either military or law enforcement personnel, and at times, medical or clerical practitioners—with the latter being longstanding co-conspirators with colonial powers and their attendant violence. The pictures usually position these figures at the centre of the pictorial plane; we never see their entire bodies, just as we don’t see their faces. The trick though, is that, unlike a usual portrait, Shumba’s figures are illegible. Though in general bodily demeanor they assume or resemble the pose or posture of studio portraiture—whose general intension is to reveal the subject—Shumba’s figures are covered up by their official garments and strange comical masks. What the viewer initially sees is a shadowy configuration thrust (usually) in the middle of a white, acontextual, background.

Like in his earlier series of abstract black paintings in which the “color” black is considered an opening to the infinite, in these drawings Shumba retreats into the dark tonal and textured renditions that explore the violence embodied by his masked figures with humor and skill. In an interview with the online publication, Newframe, Shumba talks of the color black in Judeo-Christian terms as the “beginning, the genesis,” which when read theological, would associate blackness with nothingness and lacking in potential. However, it seems here that the (non)color black is not necessarily cognized to mean closure or absence of possibility but rather to be a generative source of potentiality. This invites us to read the function of the color black here both ambivalently and openly. In images such as Gratuitous (2020), a figure in a pristine army suite and head mask stands in a self-confident posture, as if without the mask, he would be staring directly at the viewer but it is only through the attenuated layers of his humorous head covering that he is able to see us [the viewer] more clearly. It isn’t clear from which time or which army, the suit belongs. The mask too isn’t a conventional military mask but a comical feature. Likewise, the mixture of the seriousness of the military and the caricatural elements find expression in the work, and most especially the piece Non-Human (2020), in which a similar character, but in a less formalistic attire, dons a mask that resembles a blacksmith’s mask more, but with ears.

INDX – Bag, Channel – Road – Impressions, 90, 119, 250, 2020

Through these little comical gestures, or cues, Shumba attempts humor so as to indicate something uncanny in his subjects. Of course, there’s always something eerie and comedic about the state of anti-black violence which law enforcement embodies: its irrational, predatory nature always a pervasive modus operandi. His work speaks to the present by utilizing the past and invoking the violence enacted by the church, the military, and even the scientific fields, all under the guise of civilization so as to conquer and plunder black and brown nations. In this body of work, Shumba shows his capacity and potential as a burgeoning master draughtsman with both fastidious and careful attention to detail. His work is not so much exciting as it is daring—desiring an equally careful reader to keenly study it.