One of the reasons why I felt enthralled by the artwork is because the artist has mastered capturing the viewer’s eyes by forming fragmented black individuals that unapologetically return the gaze to the spectator. The artist is aware that ‘when working with black bodies, it becomes immediately political’, and in that sense the artist endeavours to force the observer into a dialogue.

Raquel Villar-Pérez in conversation with Frida Orupabo, a Norwegian artist with Nigerian heritage.

Untitled, courtesy the artist

Chaos as a way of organising thoughts.

A conversation with Frida Orupabo

Frida Orupabo is a Norwegian artist who also has Nigerian heritage. Although embodied by herself all her life within a distinctly white society, she hadn’t connected with her African background until recently. Her art practice unfolds in two very different formats that complement each other: on one hand, she mindfully crafts an Instagram account – @niemepeba -; on the other, she creates collages and photomontages.

Untitled. Courtesy the artist

I came across Frida Orupabo’s artwork not long ago whilst doing some casual google searching. Her name was next to Arthur Jafa’s on a text entitled Medicine for a Nightmare.(1) The article presented Frida’s collages shown at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo, an exhibition of the same name earlier this year. The works were distorted human figures, kind of raw, brutal and grotesque, but above all, beautifully hypnotic. At a personal level, collages and photomontages highly attract me, because I understand the multi-layered nature of these creative practice as a reflection of the multiplicity of identities, the numerous different roles that we all perform throughout our lifetime, but also on a daily basis in a world ever-changing.

Untitled. Courtesy the artist

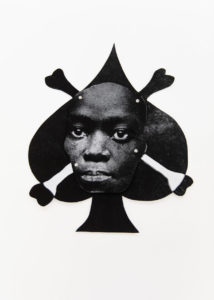

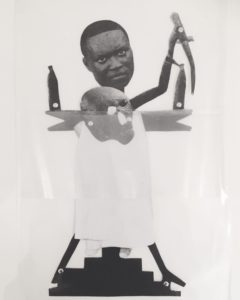

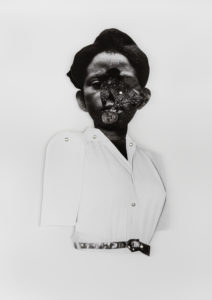

Orupabo constructs her large-scale collages from appropriated archival material that she sources mainly from the web. The research-intensive work leads her to intuitively compose disjointed black figures from cut-out images through which the artist addresses notions of race and blackness, the construction of gender, the degradation of black bodies in general and women in particular, colonial violence and pain. The artist limits her color palette to black & white and, occasionally, she uses sepia, not only because the archival material is often found in these colour schemes, but also because color itself signifies and would add an extra-layer to the already convoluted and full of meaning art pieces. She acknowledges being ‘very careful when adding color because I do not want to distort the discourse.’ Orupabo creates food-for-thought in black and white, bringing into the conversation the notion of timelessness and reinforcing the relevance of the themes tackled in her work nowadays.

Untitled. Courtesy the artist

In spite of the multiplicity of messages that stem from each work, on occasions the artist plays with polarities and ambivalence. For instance, there is a recurring presence of pigeons and crows in Orupabo’s work; these are animals present in different spiritual cosmologies, particularly pigeons symbolise love, kindness and sacrifice. Yet when they are too many and too close, they become a threat, ‘it can go from a dreamy state to a nightmare – it all depends on the composition,’ explains the artist.

Untitled. Courtesy the artist

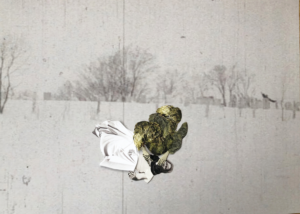

Similarly, in the image below Orupabo depicts a woman lying on the ground and a green figure resembling a bird. On one hand, the bird seems to be attacking her, but at the same time it can signify ecstasy. The green bird derives from The Winged Gorgoneio, a symbol used as protection from evil influences. The artist explains that ‘while making this collage I had a painting by Chagall on my mind. The etching is called Jeremiah received Gift of the Prophecy, which in many ways has the same ambivalence. By looking at the image it’s hard to say if this is an attack or just a loving hand placed upon Jeremiah’s mouth.’

Untitled. Courtesy the artist

The Norwegian artist doesn’t title her works. The subjects are stripped of their original context. Sometimes they are re-contextualised within a new backdrop, other times they are left floating alone. Yet no captions or explanations accompany the works, allowing for the visual imagery to stand out. One of the reasons why I felt enthralled by the artwork is because the artist has mastered capturing the viewer’s eyes by forming fragmented black individuals that unapologetically return the gaze to the spectator. The artist is aware that ‘when working with black bodies, it becomes immediately political’, and in that sense the artist endeavours to force the observer into a dialogue: ‘You shouldn’t be comfortable about my work, but rather driven into a conversation with the figures, even though you may not like them aesthetically. That is the most important thing with my work; the fact that I create subjects that are able to stare back.’ By doing so, the artist reverses any objectification of the black bodies and if, on hand they reminisce violence and pain as mentioned above, on the other, Orupabo empowers her beings to narrate stories of endurance, strength and resilience.

Untitled. Courtesy the artist

With almost 10,000 followers and 2,500 posts, Orupabo’s Instagram account has become one of the largest archives interrogating notions of race, family relations, gender, sexuality, colonial violence, trauma and identity. The artist started @nemiepeba in 2013 as a visual diary, a platform where, in the early stages, she poured images of herself and her family. Thoughtfully posting one image or text in relation to the next, the artist chose to use her account as a resource for ordering ideas that she was coming across with during her ceaseless search for a sense of belonging, of understanding how her identity had been shaped. Eventually, Orupabo started adding sourced material: titles, names, writings, movies, the work of other artists and archival imagery that helps her creating a quizzical narrative about the established ideas within which black subjects are inscribed. For the artist, her Instagram account is ‘a way of organising thoughts, a thing in itself like a collage of thoughts.’

Untitled. Courtesy the artist

In an era of image overload where we have become desensitised to the trauma and pain of others, where most Westerners remain oblivious to the historical reasons why we are privileged in this so-called global and neoliberal world, decolonial creativity functions as a wake-up call at a time where racism and xenophobia are on the rise. Frida Orupabo’s collages create opportunities for critical dialogues with colonial and imperial legacies and the spaces they inhabit today.

1. https://www.afterall.org/online/frida-orupabo-and-arthur-jafa-medicine-for-a-nightmare#.Xeo4Zi2cZ3k