In fact arts’ own capacity for re-composition and self-realization is contingent on its ability to change the world. This utilitarian trait of art isn’t something forced upon it since art can choose otherwise. Art autonomy therefore is possible only when art chooses the path consistent with the agenda of constructing a revolutionary situation and subjectivity. Thami Mnyele Lives!

Concludes Athi Mongezeleli Joja

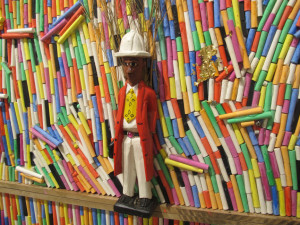

Installation view, Cape Town Art Fair.

From the Cape Town art fair to #theopening.

The Cape Town Art Fair didn’t disappoint me in any kind of way. I strolled through the jamboree with a very controlled excitement, mostly induced by the sheer pleasure of seeing new works and lingering prospects of little fun. After all, art fairs are no longer fashioned as exclusive theatres for the buying elite, but as contact spaces where the cultural public visits without the pressure of buying. Lest we forget, the term ‘public’ isn’t as heterogeneous as it appears, especially if you are black. Rather it is fraught with and reflective of all the contradictions and tensions of exclusionary practices. Put differently; in a racist world, like the private, the public is white.

Pascale Marthine Tayou (detail), 2016.

Structural racism no longer needs expressive signs of prohibition because spaces like art fairs are already regimented to reproduce systematic exclusion. Empirically, this restless dissonance in events fashioned as public, portrays the systematic barring out of the very masses by exorbitant entry fees and heightened prices that makes it impossible to even afford a bottle of water. This is a global art world problem in which “change” is regimented by the pressure to keep up with appearances, but not out of conviction. In South Africa where the meaning of public is afflicted and forked by the immediate coincidence of race, class and patriarchy, one sees clearly how the art world concurrently safeguards white interests. Here, if you are black you “enter at your own risk,” as public buildings signs would warn us.

This also speaks to the drama of ongoing student protests, more so how their political performance uncovers the pretensions of civil society. Like the art fair’s veneer of the public, universities as citadels of civil life, retain the structural characteristics of the colonial complex. By their form and content, they uphold the spatio-temporal tropes of racist traditions. And reminiscent of the June 16, 1976 student protests 40 years ago, who similarly burned down schools, shops etc. the movements’ rhetorical violence seeks to destabilize this normalised unjust running of universities as colonial cathedrals. Inspired by figures like Frantz Fanon, Steve Biko, Audre Lorde et al to decolonize that reality, students have given a new emphasis to the constructive capacity of black destruction. They have managed to speak black to the muting and disciplinary cultures of higher learning institutions.

#the opening, installation view.

Opening at the same time as the Art Fair, the group show curated by Justin Davy titled #theopening at Greatmore Studios officiates this view, through an aesthetic experience of both the student protests and related unfolding attempts. It might appear that the show’s narrative puts the rhetoric of the Fair under pressure, exposing the scales of social discontinuities that such events attempt to deny. But the irony that the Cape Town Art Fair funds #theopening might raise tensions. Yet, those fissures are also indicative of the split personality of power. That is, to appease its conscience, power is privy to staging the very conditions of critiquing its own opacity and redundancy. That is, more than this being Davy’s downside, it shows the implicit limits of power, its constant playing of catch-up to the demands of the indelible transformation agenda.

#theopening, installation view, 2016.

#theopening, installation view, 2016.

With diverse works by artists like Kemang Lehulere, Dathini Mzayiya, Wandile Kasibe, Sithembile Mzesane et al, #theopening wrestles with the multiple ways in which artists have engaged and responded to university culture, history and the visual archive. From photographic documentation to more contemplative art pieces, and not all of them as individual pieces formally strong, #theopening monopolizes on the urgency of intersecting questions: responding to the crises at hand and also of reviewing the role of cultural production post 1994. Student activism has made us question the social role of every practice, including art.

Reviewing severed relationships between art and ideology championed by Albie Sachs’ 1989 essay Preparing Ourselves For Freedom, #theopening traces the fault lines in the discursive and political framing of the cultural space. Here, Sachs provocatively prepares his comrades to see the superficial wedge that was to give art a sovereign face, ungoverned by the injunctions of protest, ideology and its solidarity criticisms. After 22 years of democracy under his ANC, Sachs’ thesis has proven to be a factory fault. In fact we must pay attention to his fallacious premise from the beginning, at that crucial point when he animatedly instructed rooms full black militias that his speech was nothing but the extension of the party’s compradorial retreat – a seize fire. His commandment was conveniently correlative with the liquidation and extinguishing of the liberation project. From this perspective Sachs’ preparatory remarks, contemporaneous with Joe Slovo’s Has Socialism Failed? (1989), should be considered to be a polite disciplining of the arts, issued by the master to secure the status quo.