“He makes clear that even the most successful African American men and White Women make good within roles scripted for them by others, in narratives that provide them with few options or real alternatives. Hoop dreams and football fantasies, like suitable marriages, happy households and feminine charms, are constructed ideals, actualized within well-defined social cages, gilded though they may be.”

Shelley Rice on Unbranded: A Century of White Women 1915-2015 by Hank Willis Thomas.

No anxious moments, 1918/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

Beware the Shadow

Unbranded: A Century of White Women 1915-2015 a parade of pictures adapted from advertisements published over the last century, is a series that stands tall on the shoulders of one of its distinguished forebears: the Untitled Film Stills by Cindy Sherman, those small, black and white photographs that packed such a powerful punch in the art world of the late 1970s. Fragments of narratives that never existed, isolated icons of story lines suggested but not actualized, these photographs succeeded in forcing us to take stock of the stereotypes that invade our consciousness every day. Hidden in plain sight, these visual clichés are so commonplace, so repetitive and so persistent that, as Roland Barthes pointed out in Mythologies, they register in our minds as nature rather than culture – as eternal truths rather than historical imaginaries. Writing in 1957 in the original preface of the book, Barthes said that his exploration of popular culture grew out of “an impatience at the sight of the naturalness with which newspapers, art and common sense constantly dress up a reality which, even though it is the one we live in, is undoubtedly determined by history…In the account given of our contemporary circumstances, I resented seeing Nature and History confused at every turn, and I wanted to track down, in the decorative display of what goes without saying, the ideological abuse which, in my view, is hidden there.” Focusing on Greta Garbo and Audrey Hepburn, on Plastics and Wrestling and the Eiffel Tower, Barthes lifted popular symbols out of their embedded contexts, unmooring them from their anchors in the image streams of mass media, subjecting them to a semiotic analysis aimed at understanding the multiple layers of what he called mythological speech.

Sherman, who grew up in the first TV generation, started to create her film stills shortly after Mythologies was published in English in the early 1970s. Mythic speech was all around us in those days: on the silver screen, in Life Magazine and National Geographic, and on those little screens that breached the boundaries between the outside world and the living room. This inversion of public and private space changed the relationship between consciousness and the world, and Cindy – hardly a semiotic scholar, deeply distrustful in fact of verbal explanations – used the film still format to embody the woman’s version of this new subjectivity. Raised in a feminist environment obsessed with psychology and the primacy of interior life and feeling, she suggested – in Barthesian terms, in fact – that there is no such thing as a person “degree zero,” an original consciousness, complete in itself, not subject to influences from the outside world. In Sherman’s universe, in fact, the walls of the Self, like the walls of the living room, have been breached; everyone in contemporary America is an empty vessel. Filled to the brim with images that bombard us every day, we become what we behold. Her film stills were not made to convey or even contain subjective emotions or feelings. On the contrary, they proposed that the anxiety, menace and insecurity she enacted on film was neither personal nor psychological, but a repeated, constant trope that defined female gendered behavior for everyone. By the time we had finished looking at Sherman’s pictures, we understood that we were reacting to culture and not nature – to a definition of woman not essential but ideological.

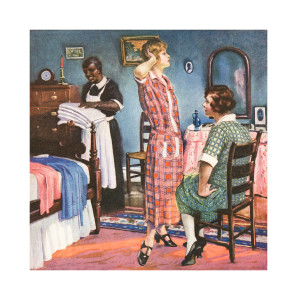

She’s got you covered, 1924/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

Hank Willis Thomas was born into this revelation, into this seismic shift that allowed all of us to unshackle ourselves from outmoded perceptions and stereotypes and to understand the power images have over our lives, our identities and our minds. His earlier related series, both employing the language of advertising because of its mass recognition and appeal, have grown out of a rich generational soil: a soil ripe for the deracination of popular imagery, and for a treasure hunt whose goal is to find the key that can unlock – deconstruct in order to reconstruct – the collective dreams and political realities of our time. Branded 2001-2011 examines the commodification of the African American male body and the charged connection between this figure and the cotton and slave trade that brought the United States so much wealth. Focusing on the similar trade in sports figures today, the series envisions a new form of slavery – this time to Nike swooshes and basketballs and bling. Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America, 1968-2008, the precursor to Unbranded: a Century of White Women 1915-2015, looks at the trajectory of images of African American life, especially but not exclusively male life, in advertising — in the constantly evolving environments and the concepts of beauty, community, mobility, relationships. Theatrical and provocative, these tableaux vivants construct – through gesture, clothing, accessories and architecture – a continually morphing guidebook for being a “successful” African American in America – from the point of view of commerce, that is.

Recalibrating our awareness that even money and fame can be a trap, that gold chains brand and bind us to stories that unfold like historically determined destinies, Thomas shows us archetypal players without agency, actors in a drama already written that predated their birth and that will outlive their death. Whereas Sherman personalizes her Selfies and her dramas, embodying the stories of battered and anxious women herself, Thomas focuses on the iconic, the impersonal and the public in his Branded and Unbranded series. (The tragedy and pain of blackness is found elsewhere in his work, the consequences that come home to roost after the slave ship has docked.) He makes clear that even the most successful African American men and White Women make good within roles scripted for them by others, in narratives that provide them with few options or real alternatives. Hoop dreams and football fantasies, like suitable marriages, happy households and feminine charms, are constructed ideals, actualized within well-defined social cages, gilded though they may be.

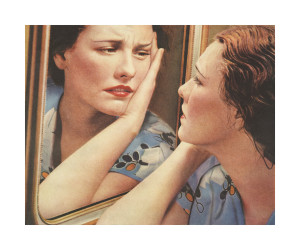

Wipe away the years, 1932/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

Unbranded: A Century of White Women 1915-2015 visualizes the construction of that cage in America, by showing us the evolution of the Ideal White Woman through advertising: her beauty, her satisfactions, dreams, options and choices. Since feminine glory is a reflected one in these ads, shining always through the eyes of men, this parade of pictures shows us not only White Women but their consorts – and sometimes captors.

There is, in fact, a photo of a caged woman in the Unbranded: A Century of White Women series. Set in an ersatz woodsy area, the picture dates from 1966, and shows a blond bombshell in a skimpy leopard skin smiling – seductively, of course – through the bars at her male captor, who seems like an Indiana Jones sort of guy. Referring, one assumes, to the Tarzan and Jane tale and the Temple of Doom – both of which had currency in the popular culture of the 1960s – the image is an ad for liquor, and one sees two cocktails awaiting the couple on the ground, among the grasses and the shrubs.

What do we make of this absurd scenario? The original ad was for Martini and Rossi, and the caption reads: “What a catch! Martini and Rossi Imported Vermouth for cocktails that purr! Try it in your own cage…” There are obvious symbolic markers on view here: the woman as “pussy” (tamed, or at least captured, and loving it) is trapped in a “cage” that is obviously viewed as a comfy domestic (read: marital) space (tolerated best with alcohol). Within the white upper classes, the targeted audience, such a scenario might be seen as funny, as satiric, the allusions to sexual tensions and abuse dissolved into humor. But for Saartje Baartman and other African women and men caged in human zoos in Europe (and Brooklyn!) during the 19th century, forced to show off their sexual parts in public, this is hardly a joke. For people enslaved and sold — in America in the past, in countries where traffic in war booty and sexual slavery is booming today – this is offensive and outrageous. But of course the whole point of an effective advertisement is that it borrows a cultural icon recognizable to its target audience, and then cleans it up, strips it of historical meaning and context in order to transform it into mythological speech: a pure image, ahistorical and empty, that signifies not a specific scenario but an archetypal way in which, in this case, men and women tacitly agree to interact in a given society.

That pure image, of course, is Hank Willis Thomas’ Holy Grail. For him, as he says (shrugging his shoulders), “the words are beside the point.” He unbrands not only white women but their depictions, taking away the linguistic frameworks that bind these drawings and photographs to the cultural stories we all know, unleashing them from the constraints of the narratives that pretend to give them some irrefutable meaning. Surrounded by written language and the familiar graphic design of magazines or billboards, pictures are justified and tamed; they can hide the fact that they are polysemous, that they speak in tongues. Left to their own devices, they are amorphous, mute and dumb, open to the interpretation of the beholder, free to float into ambiguous spaces that might instill anxiety or fear. Language and context mask what both Barthes and Susan Sontag have called the “madness” of photography, its stubborn capacity to resist fixed meanings, to become unmoored from the narratives that provide pictures with a comfortable and domesticated “cage.”

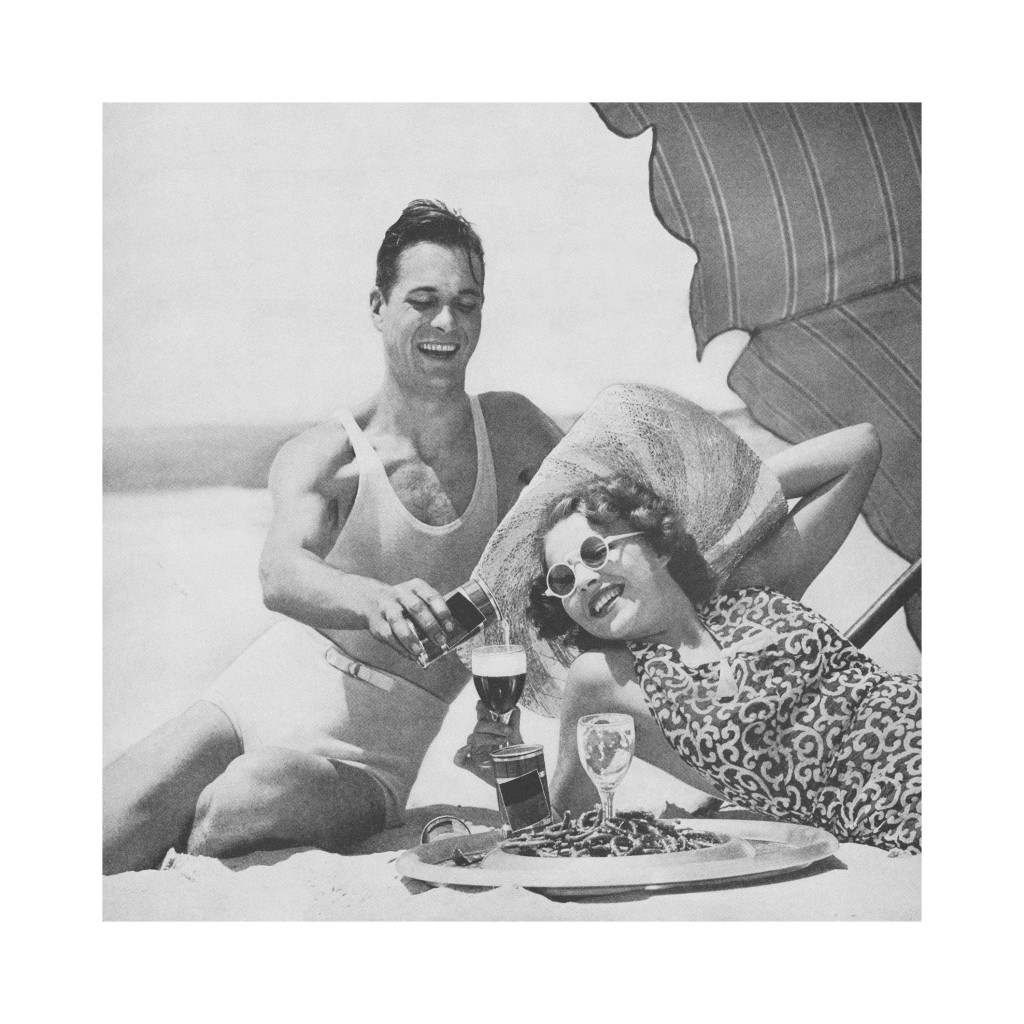

Someway, somehow, 1937/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

Someway, somehow, 1937/2015, digital chromogenic print, 2015.

These “cages” in fact need some explication, since they embody not only the references but also the temporalities of what John Berger, in Ways of Seeing, calls “publicity.” For Berger, ads must always appropriate pre-existing signs with some form of cultural currency – historical or literary characters, stereotypes or landmarks, artworks or religious symbols among them – to establish the value of their claim. The images in Unbranded: A Century of White Women 1915-2015 bear this out. They reference Mother Nature, the Pilgrims and Ancient Egypt, celebrate the “hospitality” of Southern plantations and minstrel shows, and situate themselves in the stock market and on Mount Rushmore. Rooted as they are in an established cultural image bank, these dynamic proposals – these consumer dreams — nevertheless move toward a continually deferred future, since they are only activated within the consumer’s life if a sale is made. This oscillation between past and future, between established values and latent potentialities, explains why in fact these images “move” so little. Unbranded: A Century of White Women begins around the time when new technologies of mass production made it necessary to create expanded markets in America, and to undermine the ethnic and regional differences that defined the spending habits of our diverse populations. Changes too in labor laws – the 40- hour work week and higher minimum wages – made discretionary spending (the grease in the capitalist wheel) possible for many. Corporations, growing in power and interested in selling their wares to increasingly large and diverse publics, refined the mythological speech of advertising in mass circulation magazines newly equipped with technologies for half tone reproductions. Eager to forge a market that operated nationally, that unified all cultural and ethnic differences into the singular vision (with commerce and ideology inextricably intertwined) of an American citizen, advertising gurus understood that they needed to choose their stories carefully and stick to them. And they also needed to make it clear that each of these happy scenarios has a Shadow Side: an alternative future, of loneliness and despair, of anxiety and ostracism, if one chooses not to play the game.

In fact, if one looks at the sweep of Unbranded (which is a chronological panorama of images, one selected per year by Thomas and then cleaned up, color adjusted and greatly enlarged), one realizes that the assumption that ads are “up to date” and always relevant to the contemporary moment is disingenuous. In actual fact, though suit jackets and hemlines and haircuts might change, the stories are foundational, and as such they are tenacious, indeed timeless. For a solid century, through wars and economic crises and feminists movements, women have remained “branded” by their bodies, trapped within the boundaries of their soft skin, fearful that if they lose their smiles (there are too many grinning bimbos in these pictures!) they will lose their families, their freedom, even their brain. There is an image, from 1951, that shows a woman in a straight jacket. Seen in situ, in the context of the original advertising copy, the picture is “explained.” It becomes clear that this woman was shackled by the bad bureaucratic procedures in her office; new and modern systems promise to free her from bondage. Viewed without those words, however, this is a picture of a woman in distress, tied up and helpless, struggling to free herself – during a moment in American history, by the way, when it was legal for husbands to institutionalize their wives and even demand a frontal lobotomy if they found their nagging too annoying.

The thinly veiled hostility toward – even violence against – women (surfacing especially after their impressive efforts during World War 2, on the battlefield or the domestic front) is hard to miss in this survey. There are images of women buried in the sand, hanging precariously from mountaintops (because their husbands find them a “drag” when they are outside of the home!) and proudly sporting black eyes; there are pictures of ladies being attacked by groups of men (physically) or jealous women (with cannons) or even their own kitchen appliances. Whereas we have a sense of our history as an upward spire – as a movement toward greater equality and strength – that is not the story these particular pictures tell. The feminist movement is referred to on occasion – one woman works for the phone company (and therefore can gab away while hanging from a telephone pole) and others run for political office (campaigning in their underwear!!), while Carrie Bradshaw writes on her computer (naked) – but obviously the gains referred to are illusory, powerless, without teeth. Our accomplishments in the professional world cannot, will not, alter the foundational myth, the Mother of them all: we are our bodies, and nothing more.

While we are on the subject of Carrie Bradshaw: Sex in the City was, in fact, the archetypal statement of feminine arrested development and the impotence of radical change. Carrie and her lady friends – riding high on their respective career ladders – spent little time actually working during the show. Their professional achievements (and the money these jobs brought in) were simply assumed in the television series. Their accomplishments were the backdrop, indeed the stepping-stone, for the friends’ important mission, which of course remained the same as ever: to find, and keep, a suitable man. One learned, in watching this hugely popular weekly fantasy, that girls are always on a short leash — that at some point they must go home and get down to the business of being a real, a natural, woman.

This admonition is, ultimately, the lesson one also learns from Unbranded: A Century of White Women, and it is a sobering one. Today’s little girls might want to be pink princesses in Manolo Blahniks instead of Arden women, but they have not managed to escape the cultural imaginaries that stop at the boundaries of their skin. At first glance this isn’t obvious, since in the course of the century ads celebrate women “liberated” by modern machines, free to travel in cars and trains and planes and to participate in both the work force and the Armed Forces. But look again, ladies: we might make small forays into the world, but we always end up back in our cages — smiling, lithe and content with our men and our clothes and our children. We bake and dine and dance; we primp and pose, and flaunt our breasts and legs; we serve and are served. What is most striking about this parade of pictures is how confined we are, how small the spaces we inhabit, how conventionalized and vapid the gestures we repeat and the things we covet — and, perhaps most important for our contemporary political condition, how hard these images work to disconnect us from the modern world, from public life and history. There is one picture that I can’t seem to get out of my mind. Based on a 1919 advertisement for hosiery, it showcases a man and a woman. The man is in uniform (this is right after World War I) and in a wheelchair. Young, handsome, seen in profile, the veteran looks off to the side, somewhat ruefully. He makes no eye contact with his woman, who is busy showing off her shiny stockings. Twirling gracefully, joyfully, she seems completely disconnected from her companion and his experiences, like a little girl incapable of comprehending the world of grown-ups. Ann Douglas, in The Feminization of American Culture, talks about how this infantilizing attitude toward women — more specifically, white, upper and middle class women whose husbands worked in the newly configured capitalist system, earning enough so they could insist that their wives forgo any participation in the job market and function instead as the “angel of the house” — was formulated in the 19th century, and then institutionalized in the popular culture (magazines, dime novels etc.) whose original target audience was housewives trapped at home. When we complain today about our media, about its idiocy, its disconnection, its dumbing down of the news and the citizenry, we need to remember that the roots of this problem are gendered, and run deep in the cultural life of our country. Beware the shadow, because it will inevitably come back to haunt you.

Books Cited:

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), trans. Richard Howard

Roland Barthes, The Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1979), trans. Richard Howard

Roland Barthes, Mythologies (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), trans. Annette Lavers

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (New York: Penguin Books, 1977)

Bram Dijkstra, Idols of Perversity: Fantasies of Feminine Evil in Fin-de-Siècle Culture (London and New York: Oxford University Press, 1988)

Ann Douglas, The Feminization of American Culture (New York: Avon Books, 1977)

Stuart Ewen, Captains of Consciousness: Advertising and the Social Roots of Consumer Culture (New York: Basic Books, 2001)

Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1977)