Arriving in the Netherlands was shocking. Because I realized immediately, something I oddly enough had never experienced before: that I am African. It was the first time I ever sat foot outside of South Africa and I had always just thought of myself as that kid that loved to read and draw and listen to pop music. That was my identity. When I arrived in the Netherlands, none of that mattered. People focused on my Africaness solely.

Manon Braat in conversation with London based South African artist Heidi Sincuba.

“Racism and sexism are the general ‘faceless’ enemies. That is why the black female body interests me so much in my work.”

A conversation with Heidi Sincuba

She left South Africa in 2008 to study at the art academy in Arnhem, a Dutch provincial town close to the German border. She did Goldsmiths College afterwards, fell in love with an Englishman and decided to stay in London. In the Netherlands Heidi Sincuba (SA, 1987) became known for her bold, often violent drawings of girls and women.

In June of this year Heidi came back to Arnhem, to create a new work for the current edition of Gelderland Biënnale, entitled ‘Living and Giving’. For the presentation of her work she chooses a very specific place. Exhibiting in Galerie De Buytensael, a place where tribal objects from the continent Heidi was born and raised are being shown, her exhibition is a statement in itself. In line with groundbreaking exhibitions in the past such as ‘Primitivism in 20th Century Art’ (1984, MoMA) and ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ (1989, Centre Pompidou), stirring up the debate on the Eurocentric vision on contemporary art.

Heidi’s show however does more than that. Entering the space is like a slap in the face. The first thing you see when opening the door is an army of wooden African sculptures grouped together facing you, their heads covered by pointed white hoods that immediately remind you of the Ku Klux Klan. Having to work with the ethnological objects that were already in the space and that had to stay there, Heidi gathered all the figures and installed them close to one another right next to the door, ready to attack anybody that would enter. But with their pointed white hoods, with pieces of black fabric instead of holes so they can’t see, they are silenced, entirely defused by white supremacy.

In her practice, the ghosts from the colonial past have never been far away, with the institutional racism, sexism and injustice fueling her work. This has been as much the case in Europe, as it has been in South Africa. However, as a child growing up there, she never experienced any racism, even though the apartheid system was still in place. But this is solely because Heidi has had an exceptional childhood.

“I was born in a Christian mission, a Lutheran mission to be precise. Located near the coast of KwaZulu-Natal. My parents were from two separate rural areas. One in Pietermaritzburg and one in Harding. My father was adopted by German missionaries because his father was schizophrenic and committed suicide. And my mother was taken into the mission because her mother was an alcoholic.

Those first years of my life the missionaries really looked after me. They gave us a nice house, brought me gifts from Germany. They took me under their wings because my parents came from poverty, didn’t finish high school and weren’t the role models a child needs. And being taken care of by these missionaries was super important and it made all the other black kids look at me as if I was special.

For a black child in that moment in time in South Africa I was very privileged. My best friend in the mission was a white Suisse girl, we didn’t know about the ‘divide’ between us caused by the different colors of our skin. As long as I lived in the mission, I’d never felt the reality of apartheid in the world outside. Of course it was white people running the show, doing as they pleased, but I didn’t experience any violence.

At a certain point ugly things happened, and my mother decided to leave. My father wanted to stay. Religion drove them apart. They divorced. But the mission wasn’t something you could just simply walk out of. So my mother and me and my siblings were fugitives from the mission and had to go from place to place. We lived in various townships and informal settlements. My mother started off working as a cleaner. It was a life of constant running and poverty.

Later we went to Johannesburg and my siblings and I finished school. My mother told us that she could only put one of us to university. I was pretty obvious that it was going to be me, because I was very good at school. She told me I needed to pick something that I really, really wanted to do, because this would be my one chance and I couldn’t drop out. That put a big pressure on me.

At that time, in the first decennium of the 21st century, education was kind of new in South Africa for black people. So there was this boom of suddenly being able to study. There were a few things that black people always choose mostly communications and business science. Because these studies gave you the idea that by doing those you could escape poverty. But I thought: there are enough of us choosing that path. I looked at the prospectus of the University of Cape Town and when I saw ‘fine art’ my heart skipped a beat and I knew that was what I was going to do. I had never realized before that it was something that you could actually study.”

Heidi didn’t make her mother happy with her choice, but by then her mother was working herself a way into a good life. At the time of Heidi’s graduation she had her own business. “She was driving a nice car and she bought a house. I have never had a great relationship with my mother but she was a big inspiration. I have always driven myself based on what she told me: you can work your way out of a bad place if you want it enough. That has always worked for me. At times when I didn’t have anything, my mum’s lessons have helped me to get out of miserable situations.”

As happy as she was to get into the University of Cape Town, here time there was hard. She did not get a scholarship and there were times she didn’t have any money and had to sleep on the street. But she would still go to class and study hard. She was one of five persons of color out of the sixty art students, and she was very much on her own. In her second year she had a breakdown and was brought to the hospital. A Dutch man, whom she’d known as a child because he regularly visited the mission and had kept in contact with ever since, asked her to come to the Netherlands so he could keep an eye on her. So after finishing her studies at UCT she applied at ArtEZ Art Academy in Arnhem and got in. She’d always dreamt of studying abroad but coming to the Netherlands didn’t turn out the way she hoped.

“Arriving in the Netherlands was shocking. Because I realized immediately, something I oddly enough had never experienced before: that I am African. It was the first time I ever sat foot outside of South Africa and I had always just thought of myself as that kid that loved to read and draw and listen to pop music. That was my identity. When I arrived in the Netherlands, none of that mattered. People focused on my Africaness solely. It was the kind of racism where people don’t mean you any harm but just feel they don’t have anything in common with you. “

Although black students are protesting incessantly all over the country in South Africa, fighting against the continuing institutional racism and for equal opportunities to be educated, Heidi understands why racism in South Africa somehow feels less oppressing than in Europe.

“There’s still a lot of racism in South Africa and so much needs to change. But we are being insistent about it in South Africa. There’s this urgent demand, we’re in a state of emergency when it comes to racism. There are lots of instances of extreme hate and violence, but also lots of instances where you can clearly see that white people in South Africa really have to deal with black people. They just have experience with black people that Europeans don’t have. In South Africa it’s out in the open and it’s unacceptable to refuse to see color as an issue.”

Racism has always played an important role in Heidi’s work, the consumption and representation of the black female body has for long been the central theme. On the walls surrounding the masked wooden sculptures at Galerie De Buytensael in Arnhem are drawings and paintings of a woman. Yet the new work somewhat differs from what she made a few years ago.

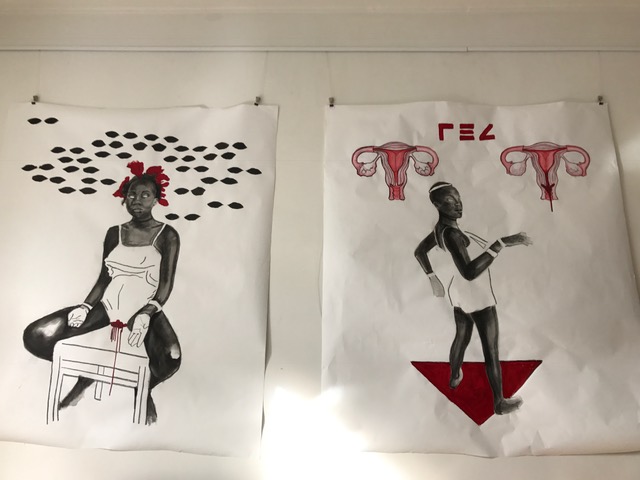

“Racism and sexism are the general ‘faceless’ enemies. That is why the black female body interests me so much in my work. I think initially I was representing the violence inflicted on the black female body quite directly, in an attempt to make people face the trauma that is exerted upon it.”

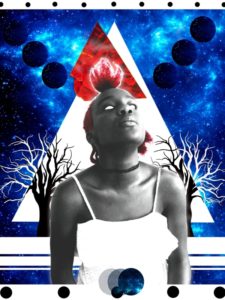

In the new works references to Zulu and religious rituals and African mythology are still there, just like the geometric patterns and the dominant colors in Heidi’s palette remained red, white and blue. Colors that have a symbolic importance for the medicines the sangoma, traditional Zulu healers, use to cure and protect people in the community. But the colors also refer to (the national flags of) the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, countries that not only are crucial in Heidi’s personal live, but that also shaped the current South Africa. Unmistakably also the satirical take on the representation of the black female body in story-telling, art and popular media is still present in the new drawings in Arnhem, but what Heidi shows is not so much African female suppression as a female African Futurism world.

Inspiration for the drawings and paintings was a young woman Heidi met at an Afropunk festival in Paris some months ago. Her name is Tirsa. From the first minute Heidi felt an overwhelming connection with Tirsa and asked her to become her muse. Tirsa was born twenty years ago in the Netherlands, Heidi a decade earlier at the other side of the world. They have the same color of skin and face similar difficulties in this world. Through Tirsa, Heidi shows a black woman’s world. By portraying the woman in many different ways, even including bits of their written dialogues in the exhibition, the audience gets to see all aspects of a person: the strong, the proud, the insecure, the vulnerable, the lust, the anger. Nothing is concealed. Even the mental health problems both Heidi and Tirsa have had to deal with in their lives and that is not commonly spoken about in many black communities, as well as the bodily pain while menstruating, are not avoided. People may think that the image of the woman with the bleeding vagina refers to female circumcision, but it does not. Heidi deliberately uses bold images like these to play with the viewers’ expectations.

This exhibition is not a realistic representation of her or Tirsa’s world; it contains elements of both their lives, combined with elements of historical fictions and facts, cosmologies, fantasy and magic realism, challenging European preconceived ideas about Africa, and black women.

This month Heidi will travel to Johannesburg to participate in the ‘Black Portraiture’ conference and exhibition organized by New York University. Being able to exhibit her work in South Africa is something she’s particularly happy about. She knows there’s so much going on in Johannesburg and Cape Town and that people, some of her old class mates even, are starting project spaces where upcoming artists have a chance to show their work to the public. That’s why she thinks South Africa is more of an inspiring place for her to be than London. Eventually Heidi wants to go back to her home country permanently and be an inspiration to a young generation of black South Africans, who dream of making a bright future for themselves. She’s always aspired to travel the world, get a great education abroad and then come back home and live well.