History shows that villages, cities, as well as countries need a diverse population with varied talents and abilities in order to thrive. The work of artists like Griffith and Locke reflect that concept and remind us of the important role that an engaged citizen can play in their community.

Sasha Dees reports from the Tate Modern performances of Marlon Griffith and Hew Locke.

Up Hill Down Hall

Marlon Griffith & Hew Locke

Informed by the history of the Notting Hill Carnival as it reached a milestone half-century of existence, Up Hill Down Hall in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern in London kicked off carnival weekend with performances by artists Marlon Griffith and Hew Locke.

1.

‘No Black in the Union Jack’ by Marlon Griffith, which began Saturday afternoon, became disturbingly real because of the running battle between the police forces and local protesters in Ferguson, Missouri (USA) after a policeman shot and killed Michael Brown a black teenager. Londoners had seen and experienced a very similar incident firsthand when their police force shot and killed an unarmed man, Mark Duggan, in Tottenham in 2011. Asked to participate months ago, Marlon Griffith took the 2011 riots in London as inspiration for his performance.

In both cases the police desperately tried to control the narrative, the official story portraying the victims as brutal, armed attackers; then, when that turned out not to be true, criminals that ‘looked’ armed. Though the lies kept falling apart the harm by the media was done. The victims, in the eyes of many, were stuck being at the least thugs who deserved to die. More so then not, things are never what they seem and look different from different angles.

(photo copyright Tate 2014)

(photo copyright Tate 2014)

Griffith worked (as he has in the past) with Elimu Paddington Arts Mas Band for this performance. TATE volunteers and other interested ‘outside’ volunteers were added to the band. All masqueraders were dressed in black pants and hooded black sweaters, making a blurred line between masquerader and policeman all the while reminding us of yet another event, the Trayvon Martin case. (1) The masqueraders held life size shields made by St. Martin art students supervised by Griffith.

Griffith resides in Nagoya, Japan. His first introduction to Japan was for a Residency in the Mino Paper Art Village. He specifically went there to learn Japanese folding and cutting techniques. Since then, Griffith has developed a very authentic recognizable style in his art practice in which he effortlessly blends Caribbean Carnival and Japanese Origami and Kiri-E techniques.

This work plays off the idea of the police riot shields and originally Griffith had wanted to use acrylic sheet that would have a similar transparent look of these, but due to budget restraints he had to use correx sheet. Correx sheet is normally used for packaging and other applications and covered with window tints, which added a more dynamic, stealth, militaristic, futuristic type of appearance. The light material also gave the appearance of being heavy as metal.

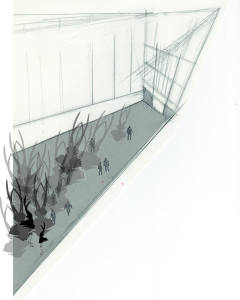

Sketch, 2014

Sketch, 2014

Griffith has always worked a lot manipulating particularly paper. Working with plastic was a big step and achieved amazing results. He went through a whole process of drawings, maquettes and more maquettes which played a big part in the success of the structures. Griffith choreographed the performer’s movements, and depending on how the light fell, the shields transformed from black to metal to reflecting mirrors. The shield not only had a visual presence but the way the performers held the shields immediately, psychologically puts them into a certain state of mind.

(Photo copyright Akiko Ota Griffith 2014)

(Photo copyright Akiko Ota Griffith 2014)

The shield design is also based on hummingbird patterns which Griffith abstracted to create the specific patterns used in this project. The humming bird is an image he uses from time to time in his work to reference the Caribbean. Most importantly the bird is extremely territorial and aggressive which worked out perfectly within the Turbine Hall project.

The performance, which included sixty performers under Griffiths’ direction, began at St. Paul Cathedral. The Mas Band, the traditional term for a themed Carnival procession of costumed performers and musicians, crossed the bridge over the river Thames towards the Tate Modern building. A wedding had taken place at the cathedral moments before. The wedding party merged with the procession, no doubt resulting in unique phOtas of their everlasting union.

At the entrance to the Turbine Hall, the Mas Band stood waiting in formation, on high alert, much like armies of yesteryear on the appointed field of war where the battle would take place at sunrise. At exactly 3PM the group charged towards and into the Turbine Hall.

The packed space saw the performers change from knights going to the battlefield, to a carnival mas band to a police force charging towards us, restrained but without reluctance. The underbelly feel of a threat and fear was amplified by the soundtrack.

Griffith likes to collaborate with musicians for his projects on sound design in this case Dubmorphologhy (Gary Stewart+ Trevor Mathison). In this project the soundtrack came from ankle bells worn by the performers and an amalgam of sound as an organized chaos. Griffith identified very specific sounds he wanted to work with. He drew mostly from audio of the riots but also carnival noises, sound system clashes somewhat re-creating or creating a new environment in which the work then inhabited. It also included the “Hackney Heroine” Pauline Pearce; she gained fame from a camera phone video showing her berating looters when the riots spread from Tottenham to Hackney. Added were courtesy Dubmorphology excerpts from interviews of people who experienced the early Notting Hill carnival and riots which pulled it all together.

(Photo copyright Akiko Ota Griffith 2014)

(Photo copyright Akiko Ota Griffith 2014)

‘No Black in the Union Jack’ referenced recent international events in Europe, US and the Middle East that have touched us, unifying global citizens in a forceful demand for justice. Griffith gave a strong social political message and undertone for which art in general and Carnival traditionally has been and will continue to serve as a platform. Griffith is an emerging force to be reckoned with, a master in playing both the more populist Carnival field as well as the contemporary art field. I for one cannot wait to see a procession of his creation going through Venice as part of a future biennale!

2.

The start of Hew Locke’s performance created some confusion as it was expected by many to be elaborate and very colorful. Locke’s work, which has always been linked to the Carnival, is famed for that.

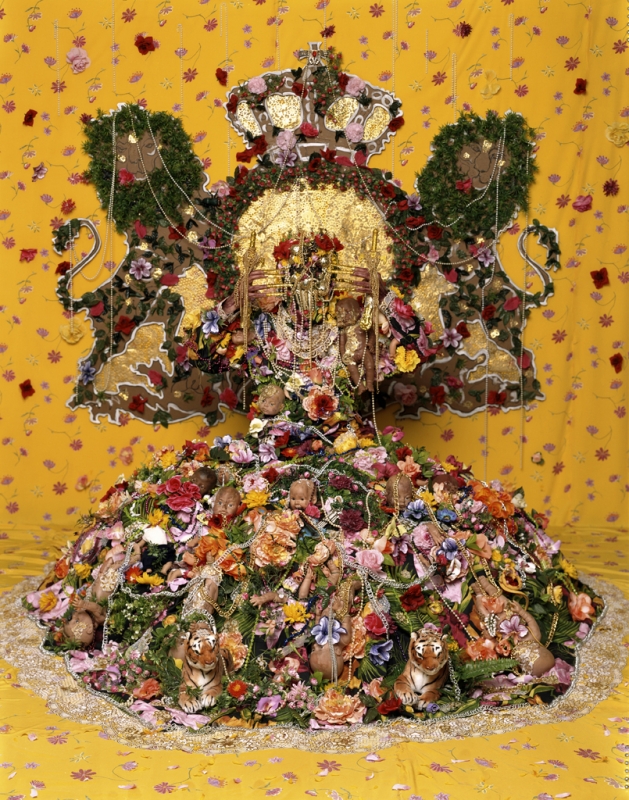

Hew Locke, Serpent of Nile – 232 x 182 cm – C-type photograph (from ‘How do you want me’ series , 2007)

Hew Locke, Serpent of Nile – 232 x 182 cm – C-type photograph (from ‘How do you want me’ series , 2007)

Carnival comes with a high price. Carnival costumes average US$10.000 per outfit to make. Locke’s artwork, as in the photographic tableaux shown here, cost about £8,000 to produce. Not to speak of the army of volunteers that Locke would have needed to make 60 such costumes in the allotted time, alongside several other projects he has in progress. Considering those facts as we should have, we couldn’t have expected 60 samba band members dressed not ‘just’ only in a carnival costume but in a ‘Locke art work’. (Secretly I kept wondering though about what a totally breathtaking gorgeous sight that would have been!)

Hew Locke, Tyger Tyger – 232 x 182 cm – C-type photograph (from ‘How do you want me’ series, 2007)

Hew Locke, Tyger Tyger – 232 x 182 cm – C-type photograph (from ‘How do you want me’ series, 2007)

Like Griffith, Locke also stayed true to the Carnival tradition of it being socially and politically engaging. ‘Give and Take’, Locke’s first performance, which he made with Batala Samba-Reggae band talks about tensions around the history of the Notting Hill area, the changing cultural influences on the carnival, and a personal reflection on his memories of living in Notting Hill and how the experience of attending carnival has changed over time. The issue of gentrification affects a large group of people either being gentrified or gentrifying.

(Photo copyright Indra Khanna 2014)

(Photo copyright Indra Khanna 2014)

Locke’s performance was the closure of the afternoon. It started with drumming as 50 masqueraders slowly walked into the hall. They held shields and sticks the exact form and size of those used by police troops in reality. The shields showed pictures of houses around Notting Hill, including the house where the artist lived in the 1980s.

The masqueraders went into a formation at the short back end of the hall and started beating their sticks against the back of their shields. First they went through the audience while beating their sticks. After a while they spread out over the width of the space, pushing the audience from one end to the other.

With intervals of just drumming, the audience kept being pushed around. At a certain point as an audience member you begin to think, “yeah, yeah, I get your point,” and Locke gives it yet another two pushes. Then comes that point where you feel really kind of frustrated and over it. Locke deftly manages the effect of building the right sense of frustration in his audience members that pushed out communities live with: just let me be and have the pushing around stop, it’s enough now!!

We all know that gentrification is hard to beat and many of us have enjoyed the benefits that come with it, like the better grocery stores with fresh produce. But regardless of our economic status, we all need the basic necessities which include a place to call home.

History shows that villages, cities , as well as countries need a diverse population with varied talents and abilities in order to thrive. The work of artists like Griffith and Locke reflect that concept and remind us of the important role that an engaged citizen can play in their community.

Check a video of Griffith’s performance:

Watch a video of Locke’s performance:

Watch a compilation of the event (including the St.Martin performance not written up in this article):

Note:

1) On the night of February 26, 2012, in Sanford, Florida, United States, George Zimmerman fatally shot Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old African American high school student. George Zimmerman, a 28-year-old mixed-race Hispanic, was the neighborhood watch coordinator for the gated community where Martin was temporarily living and where the shooting took place.

Running and future exhibits:

Up Hill Down Hall was a prelude for ‘En Mas’: Carnival 21st Century Style’,

March 6, 2015 – June 7, 2015, Contemporary Art Center, New Orleans, USA

‘En Mas’is the first major scholarly curatorial project to account for the influence of Carnival on contemporary performance practices in and of the Caribbean, North America, and Europe. ‘En Mas’ charts an alternative path for performance art in the steps of Carnival and other festivals in the Caribbean and its Diasporas. ‘En Mas’: Carnival 21st Century Style’ is curated by Krista Thompson and Claire Tancons and co-organized by Contemporary Arts Center New Orleans (CAC) and Independent Curators International (ICI). It is made possible by an Emily Hall Tremaine Exhibition Award with additional support provided by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Marlon Griffiths work can also be seen:

• October 4-November 15, 2014 – Beyond Limits: Post global Mediations, San Diego Art Institute a satellite exhibition of the mediations biennale Pozan, Poland

• November 16 – Feb 22, 2015- All Masquerade! Carnival and Disguise in Art , MEWO Kunsthalle Memmingen, Germany

• Summer 2015 – AGYU Art Gallery of York University Artist in Residence: working on large-scale “Toronto Project” which will culminate with a public street procession presented in conjunction with Parapan Am Games,Toronto, Ontario, Canada

• Summer/Fall 2015 – Solo Exhibition(untitled) Summer and Fall 2015, AGYU The Art Gallery of York University, Toronto, Canada

Hew Locke’s work can be seen:

• September 18-21, 2014 – EXPO Chicago (Halles Gallery), Chicago, USA

• October 10 – November 22, 2014 – Beyond the Sea Wall – Halles Gallery, London, UK

• October 25, 2014 – January 25, 2015 – Prospect.3, New Orleans, USA

• December 12, 2014 – March 31, 2015 – Kochi-Muziris Biennale, India

www.marlongriffith.com

www.hewlocke.net