I think I wouldn’t encourage people to become full time artists. I never even encouraged my students to become full time artist because you don’t go to school and learn to become one. Being an artist is a calling, you are either called to be that out of a need inside you or you are driven by circumstances. But I encourage most of my students to be creative, always question and be productive. The only way we can show our worth is through what we say and do, in other words through action. The more you say and do good things, the more you are considered productive and the more you will be rewarded.

Matt Kayem in conversation with the Ugandan artist Henry ‘Mzili’ Mujunga

Dripping Earth, 2019. Courtesy Circle Art Gallery

BEING AN ARTIST IS A CALLING

In Conversation with Henry “Mzili” Mujunga

Mzili is also known as the General or you could call him the father of Ugandan contemporary art. As an artist, art teacher, mentor and writer, he has contributed a lot to shaping the art scene in Kampala. Among other achievements, he cofounded Kampala Arts Trust and was curator of the first edition of the Kampala Art Biennale. Mzili is a winner of the Royal Overseas League (ROSL) Art Scholarship 2003 and has exhibited work in OSTRALE 015, Dresden Germany, Johannesburg Art Fair 2016, Cape Town Art Fair 2017 and Close 2018 at the Johannesburg Art Gallery. His work is part of the Africa Now! collection of the World Bank Art Program.

*

Henry’s portraits feature numerous, seemingly disparate objects brought together into a single frame. They are set in intimate spaces where highly personal interactions take place – often combining several such spaces into one – with titles that the describe the interactions within the paintings themselves, and at the same time allude to external associations. Mzili’s gathering of objects, spaces, and the existing associations with these objects mimics the processes of identity-making that he observes in his native Uganda. Individuals often rely on their outward appearance, their possessions, even their environments (and their interactions within them) to communicate their own vision of themselves. At the same time these very things are looked upon by others to identify those around them. Through these information-packed autobiographical compositions, Mzili offers a glimpse into his personal history and present. In addition, they become, for the viewer, a point of departure from which to begin building an understanding of identity in present-day urban Kampala.

*

For the last 20 plus years of his career, he’s been an advocate of ‘indigenous expressionism’, a movement and ideology he gave birth to. Mujunga made his debut at the prestigious 1:54 art fair in New York which was held from 2nd to 5th May 2019. He is the third Ugandan artist after Paul Ndema and Ian Mwesiga to show at this platform and this was my basis of hunting him down for an interview. I had been trying to get to him for the last two weeks and on a Sunday like the last one, luck was on my side as he ditched his busy schedule to sit down with me. Our conversation was a broad one like his work as I steered him from his beginnings as an artist to his varied concepts. We talked deeply about sexual orientation and gender as well as future Africa.

Mzili narrating to me at his studio. Photo by Saidi Stunner.

MK: Let’s start from the beginning. How did you end up as an artist?

HMM: I studied art at Margaret Trowell School Industrial and Fine Art at Makerere University. I graduated with a Bachelors in 1996, tried to do business for two years, hated it and then I just fell back into art. Before that, I was always expressing myself through drawing as early as primary school. We would draw movie stars, cartoons and comic book characters as seen through cinema from Hollywood. I also liked building small mud houses, I had a bias towards buildings because my earliest recollection is that I would build detailed small buildings using found objects. In lower secondary school, I was drawing a lot of high rise buildings and sky scrapers in my books, unfortunately I lost all those books and that interest. So by the time I was finishing secondary school, everybody knew that I was gonna be an artist. There was another classmate they thought he would be a lawyer and it was the two of us whose future careers were very certain. I was also largely inspired by my older brother who was an excellent draughtsman. He went to Margaret Trowell too and he had also majored in drawing special at the medical school. You know, that kind of drawing done on cadavers, DaVinci style, that one. He was really good but unfortunately he never became an artist. But maybe God choose me, I was the crazy one, to follow this path.

*

MK: And the pseudonym, “Mzili”, how did you get this?

HMM: Mzili is a very interesting name which I got in my second last year in secondary school when I presented a paper on Mzilikazi Khumalo, the southern African king. My classmates enjoyed the presentation so much that they started calling me Mzilikazi in a mocking manner. Later, they made it more funky and turned it into Zilix. I cut it short to Mzili because I thought it was too long and it stuck, I embraced it more. By university level, everyone was calling me Mzili. I took it as my art name too because it also had a historical significance and background to it, for Mzilikazi was a great military leader who rebelled against Shaka Zulu’s tyranny.

*

MK: Congratulations on your debut at 1:54. Do you think it is important for you to show at such a platform?

HMM: Yah, it is very very important because for a long time there is been a complaint that Uganda is not visible on the global art scene. You remember when Simon Njami ridiculously said that there is no art in Uganda. His defense was that he doesn’t see Uganda artists on the international platform. So when we start penetrating these platforms, it is a good thing although I’m aware that they are also highly elitist. They are designed to create bias and interest for those collecting art to make more money but generally it is important that I’ve had the chance to show there. My overall experience at the fair was a positive one, my work was well received. I exhibited with a young vibrant Ethiopian lady which got me more visibility. But also my work was seen as a current symbol of Afrofuturism, like the progressive Africa as you know my work is about space travel, the dryers, you know a comical and dreaming new image of Africa. One of my works was on the cover of Whitewaller magazine and I got very good review from the media.

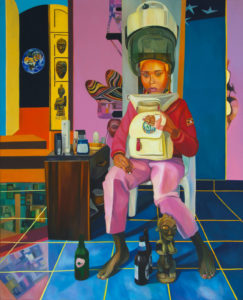

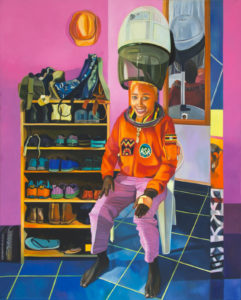

Travelling Shoes, 2019. Courtesy Circle Art Gallery.

MK: I haven’t seen a solo exhibition of your work since Six Degrees of Separation in 2016 yet you were the kind who was known to have one every year.

HMM: Yes, there are so many changes that I’ve occurred in the way I work. First, I used to work for a small gallery, Afriart Kamwokya and we used to work in small formats and it was easy for me to accumulate work. Now I’m working on large format and these are pieces that take me months to produce. So for me to produce enough work for a show means that I will not be selling any work and yet my work is on high demand with some people booking the work before I produce. Already I have two pieces booked now (points at two blank large white canvases). Unless I contact mu collectors to make a show for me and I make a few other works and add them in there. Otherwise, it’s not easy for me to accumulate enough work for a show. But I’ve been showing at international art fairs and my occasionally showing up in auctions at Piasa and in Nairobi. I also think this whole idea of exhibitions is old fashioned, their purpose is to publish work and if one is doing it through other means, then there is no reason for a solo show.

MK: What’s your process of working? How do you arrive at the finished piece?

HMM: I create the idea and after that I take photos. I use photography as a tool to sketch out my ideas. I collect the pictures, and make a set. I end with a collage and I make reference to when I’m painting but I can alter things as I work depending on how I feel. But I always try to be as accurate as possible not to have my message and imagery lost in translation. I don’t want to lose information as I move from one medium to the next so I always try to stay as close as possible without necessary duplicating it but it gives the accuracy. Some people end up calling my work realism but my work is still indigenous expressionism, it’s the way I was taught to work and also born intuitively to.

MK: You have painted, sculpted and done print-making among other artistic areas. What led you into concentrating on painting as a means of expression?

HMM: I actually majored in sculpture at the university. I did graphics, painting and sculpture in my first year, and second year, I narrowed it down to sculpture and painting and ended up with sculpture in the final year. But then sculpture is so heavy and tedious, I did a lot of monuments and public sculptures around town after university. I found sculpture very tiring and not rewarding. People contract you but don’t pay for what your work is worth. And also the tools and materials for sculpture were hard to come by then. If I was doing sculpture, I would love to do huge works like what my lecturer Professor Naggenda did. Then in print making, I had discovered a technique to work from dark to light reversing what everyone was doing that time which was light to dark. But then, I found that tiresome and delicate plus the health hazards that came with the inks we used made the medium harder to continue with. And then also having to frame the work. With painting, I’ve always found it interesting, you know, you sit down, develop a concept. And also I wanted to make something that could easily be carried away by a buyer and most of our clients were expatriates and people from outside of Uganda. They would find sculpture and print work bulky and fragile because of the glass. Commercial reasons at the end of the day led me to painting.

*

MK: Your work has changed concept wise and aesthetically over the course of your career. From the indigenous expressionism period to the figurative approach we are seeing now, which is something quite different from your work of say ten years ago. Why is that?

HMM:. My work has always been figurative, it’s only that my work has become more clearer, my portrayal of the subject has become more simplified.. It is no longer a cacophony of noise because before, my work was a burst of ideas creating these lines and colors, what one would call abstraction. In a way, my work is still abstraction because to abstract is to simplify. So my work has always been figurative, one thing I can say is that I have placed emphasis on drawing, I’ve always been good at drawing. It doesn’t mean that if you’re an abstract painter, you can’t draw. I’m drawing more now and I’m picking from nature. So I started the conversation of why we are doing things people do not understand. Yes, they are clever and beautiful but why do you want to become so clever that people around you don’t understand you. People were always complaining about our abstract work, I had even coined the word ‘volongoto’ as an ism for my work. Volongoto is a derogatory word in Luganda which means a mixture of things. So there was this divide where a bunch of artists did realism and we did abstraction and no one crossed the boundaries, either parties respected each other. So I broke the mold when I did Buffalo Woman in 2010 which was different from my usual work. I created a wave which has been continued with Paul Ndema. So I wanted to create simpler and clearer work. There is no better lesson than one from nature and there is nothing new under the sun.

*

MK: Your work takes on a maximalist approach, there is a lot you are trying to comment on, so much symbolism, from African history to present day identity politics. It speaks of an artist who reads and researches deeply. How do you arrive at these concepts?

HMM: Essentially I’m inspired by those around me, especially my friends. Some of the stories I’m creating about gender are coming from my experience of gender biases among my female friends. And I’ve seen people here in Uganda not understanding issues of gender and they end up drawing these lines, male and female, period. So all these guys who fall in between, who don’t identify as either, or, who want to cross over are disregarded. You know, we used to laugh at these boys who acted like girls, we had a boy we called Julie, you know, the teasing. But I didn’t take part in that, I was always watching and empathizing with someone in that position because some of my friends were like that. I used to read extensively and I observe a lot. I have a deep background with African history. I like philosophy, science and knowledge. I like human knowledge with all its breadth, you know, space. I always watch national geographic. I’ve always had this hunger to know more since childhood. So I get all these ideas and sometimes it’s difficult to them. Danda once called my work a symphony, different ideas coming together to make a song. So unless you love my music, you won’t be able to relate to my song.

*

MK: You know, so many people have referred to you as ‘the one with a well of ideas’…

HMM: Hehe, that is Kafulu Xenson, I’m the General, but I’ve always been a smart guy even back in school when I was always on top of my class.

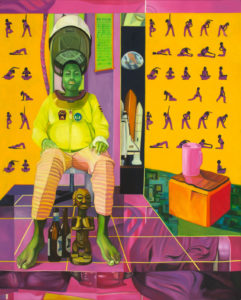

Antenatal Trip, 2019. Courtesy Circle Art Gallery

MK: So you don’t have any other enhancers or secret elixirs to help you create or develop ideas…

HMM: Alcohol is very good, he he, like I always tell people that substance use is not abuse. I drink alcohol and sometimes it makes me think more clearly and creatively.

*

MK: Before this new work, your old work touched on issues of gender and the shifting paradigm towards a “new normal”. I think it was very important seeing that every day we wake up to a new letter added to the ‘LGBTIQ…’ movement. And within all this, you seemed to say there is somebody at the top holding the strings and making the puppet dance, creating a new structure for social control in this age of attention seeking.

HMM: Yah I’ve said that, I’ve said that all these gender identities have been there before. In some societies they are suppressed and in others they were left to flourish. But then now, somebody is drawing political and economic attention towards gender identity. And also now, we have an issue of trends, what is trending? Nowadays it’s cool to relate with the LGBTQI. So I think it’s so simple when you look at it from the view of what people want to be. If someone, a “man” feels like a woman, it shouldn’t be a crime, unfortunately it is here in Uganda. It’s a feeling one wants to express but what I don’t understand is when one goes an extra mile to change their bodies. I thought it was only necessary to let someone live comfortably with their feelings of being in the wrong body. I don’t fully understand it but I think this global façade we are seeing now is tending towards an underlying political and economic intrigue.

*

MK: The work that was on show at 1:54 deals with the contentious subject of identity. What is your understanding of this in relation to present day urban Kampala?

HMM: Identity in Kampala is quite interesting because right now we are picking on a global identity. We no longer have these clear cut boundaries among the sexes. When we were growing up, they could tell us, a man wears a trouser and cuts his hair short. Then for us we decided to grow our hair not because we were rebelling, but we wanted to express ourselves differently and then the trend picked on. And also, this is one of my theories, many of us where brought up by single mothers so we identify better with our feminine side. You see, these young men are all becoming softer, wearing tight pants and therefore men don’t feel the need to be macho anymore. And also the ladies because of the hustle of the city have become tougher to survive and it is working.

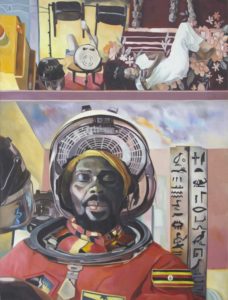

The Afronaut, 2018. Courtesy Circle Art Gallery

MK: Your painting at the fair, Afronaut seems like a shot from a sci-fi movie, with you suited up for a trip to another universe, yet a mirror reflection of your wife show that your journey is more likely a fantasy born in the mediated world of your smart phones. Please tell us more about this work.

HMM: That work was actually my first Afronaut work. I was sitted in a salon having my hair dried and it happened that the salon had a mirror at the back which was inclined at an angle. So I saw the image in the mirror at the back and I thought it was amazing. You have two worlds, one world reflecting the other but I had to make reference to the current social media frenzy. I also know that in my narrative, my wife represents the younger generation, the dot com age while I represent the television age. So basically we are two people from different generations who go through life together and compliment each other and share lives together. So I wanted to bring these divergent images together and still emphasize the divide, that’s why you see the separated areas. So she’s there dressed in white symbolizing purity and I’m there with my desired to fly. So the whole scenario and especially the hair dryer made for good allegory for space travel.

*

MK: Your work also references the potential of an African space program. With this in mind and the ideas of Cheikh Anta Diop and Thabo Mbeki, what do you think is the future of me and my generation?

HMM: Interestingly, I just learnt about this recently when I was reading an article about my work, that in 2007, they inaugurated the African Space Agency. I thought mine was called the Afro Space Agency. And even the logo I used is mine and I’m going to patent it. I wanted to mock, everyone thinks that Africa will make progress but unfortunately it’s always lagging behind because we are always catching ideas that others have regurgitated. So Africa started to explore space today, they would start with where Russia and America started from in the 50s. So the whole idea of Afro Space program is a joke but a beautiful one because for us Africans, we travel with our minds. I have been to space, maybe I’m the first African there so I travelled there mentally because the others have beaten me to there.

Me(Matt Kayem) and Mzili seated outside his house chatting away. Photo by Saidi Stunner.

MK: As someone who has tutored young people about art. What do you think they are lacking or the system is lacking? How do they better their hopes of becoming full time artists?

HMM: I think I wouldn’t encourage people to become full time artists. I never even encouraged my students to become full time artist because you don’t go to school and learn to become one. Being an artist is a calling, you are either called to be that out of a need inside you or you are driven by circumstances. But I encourage most of my students to be creative, always question and be productive. The only way we can show our worth is through what we say and do, in other words through action. The more you say and do good things, the more you are considered productive and the more you will be rewarded.