“In the Black Fantastic will be the first exhibition to highlight this very significant and still under-acknowledged artistic territory that extends across the field of visual art to recent trends in literature, film, television, and music”.

Christabel Johanson quotes Ralph Rugoff, Director at the Hayward Gallery

Installation view Hayward Gallery (work of Rashaad Newsome)

The Future of Afrofuturism:

In the Black Fantastic

In the Black Fantastic is the UK’s first major exhibition dedicated to black artists who use “fantastical elements to address racial injustice and explore alternative realities”. The artists all remake familiar tropes and themes within mythology, folklore, spirituality, Sci-Fi and more to create a vision of Afrofuturism. The exhibition showcases special commissions as well as totally new works of art that encompass mixed media including sculpture, video, painting, photography and installations.

The show is curated by Ekow Eshun and centres on how the artists “reimagine the ways in which we represent the past and think about the future, whilst also engaging with the challenges and conflicts of the present. The fantastical element has nothing to do with escapism; instead it considers alternative ways of being, and confronts socially constructed ideas about race”.

This multi-layered work brings the viewers into a textured aesthetic, somewhere between the familiar world and somewhere new. This feeling of uneasy familiarity can be characterised by the German term unheimlich. Translating literally into the term “unhomely”, unheimlich is a psychological experience that evokes something unsettling, creepy and uncanny.

This aspect of uneasiness is harnessed to good use here as In the Black Fantastic sometimes brings forth a dystopian edge to the future, as it intersects the borders of race and identity. For example, the distressing yet familiar slavery narrative of our reality is reimagined by artist Ellen Gallagher.

The slave trade across the Atlantic Ocean is retold in her mythic paintings that call to mind the legend of Atlantis alongside an alternate reality. In this reality there exists an underwater community inhabited by the descendants of drowned Africans across the Middle Passage.

The Middle Passage was an infamous stretch of the slave trade and its voyage through lasted roughly 80 days. Many slaves brought over from Africa died from disease, poor ventilation or dehydration.

Ellen Gallagher, Ecstatic Draught of Fishes, 2021, Oil, palladium leaf and paper on canvas, 249 x 202 x 4 cm, © Ellen Gallagher. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Tony Nathan

Eshun reflects that “as a concept, the Black fantastic does not describe a movement or a rigid category so much as a way of seeing shared by artists who grapple with the inequities of racialized contemporary society by conjuring new visions of Black possibility. More than ever Black visual artists, as well as writers, film-makers and musicians, are thinking in boldly imaginative terms in order to explore race and cultural identity in the contemporary era.”

By this token, the vision of a Black reality where Gallagher’s characters exist are a stark reminder of the racial inequalities and atrocities that slaves faced. It is a condition that the Black community can still face. This is a bold exploration of the “what ifs” in history. As much as the Black community today have roots in slavery, Gallagher’s reality positions the viewer in the shoes of these mythological descendants, who are the focus of her work.

Ralph Rugoff, Director at the Hayward Gallery describes the show as “at once vivid and thought-provoking, lyrical and relevant, the works in the show embody the power of the fantastic to help us chart new ways of confronting legacies of racism and celebrating cultures of resistance and affirmation.”

On that note, Lina Iris Viktor uses regal symbolism to offer us another embodiment of race. In her work she fuses fantastical elements alongside vivid colouring, ranging from the golds and blues, that are in keeping with African traditions. “Viktor’s mixed-media works draw from sources including astronomy, Aboriginal dream paintings, African textiles, and West and Central African mythology”.

Lina Iris Viktor, Eleventh, 2018, Pure 24 karat gold, acrylic, ink, copolymer resin, print on matte canvas, 165 x 127 cm, © 2018. Courtesy the Artist

In the above piece, traditional African patterns frame a woman who is set against a golden “throne” shaped background. The figure feels regal although she is not draped in ostentatious jewellery, it draws in the viewer into a narrative about Black excellence. Her hair is strikingly styled and she has an obvious dark black mask on her face. Could this be an evocation of “black-facing”? If so, what effect does this have when a lighter skinned Black woman is presented in such a way? This is a thought-provoking union of culture and fashion, of tradition and the fantastical.

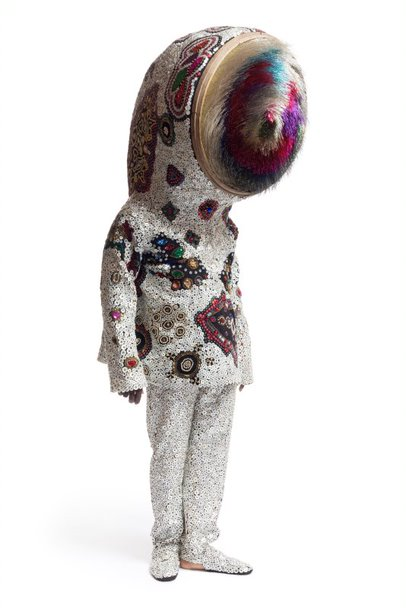

Another featured artist is Nick Cave whose piece entitled Soundsuit is an otherworldly submission into the exhibition. It is part of a larger collection of Soundsuits, intended to be worn and danced in. These have been called “wearable sculptures” most likely because they are as arresting in isolation as a costume or showcased as freestanding art.

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2014, Mixed media including fabric, buttons, antique sifter, and wire, 211 x 60.5 x 67.5 cm, © Nick Cave. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Mandrake Hotel Collection

The suits are made from objects found in flea markets as well as woven fibres made from twigs, yarn, hair amongst other things. As the suits become kinetic during performances, Cave adds another dimension to them by attaching pots, tins and anything else that creates a sound. With their eye-catching styles, glimmer and astronautical chic, these pieces transform the Black body into a walking billboard, a protest on legs or an alarm call. They could become the protection needed to keep a Black body alive (within Earth or Outer Space), or they could be the shelter in which to retreat and hide away. Cave’s suits become another skin and through this function, the viewer is invited to see the vision of the Black body in a new and revised way.

Furthermore, what if Cave’s suits are a representation of an inner self, an aura in all its beauty? If it is a revelation of the soul without discrimination or without judgement of skin colour, then he presents a vision of the future where we can truly see more than meets the eye when society is not blinded by prejudice. It is a picture of a future where Black brilliance is celebrated.

As an artistic expression Afrofuturism explores the Black experience from a unique perspective. Rugoff comments that, “In the Black Fantastic will be the first exhibition to highlight this very significant and still under-acknowledged artistic territory that extends across the field of visual art to recent trends in literature, film, television, and music”.

The term, which was coined in 1994, has seen a steady increase in popularity. Its aesthetic and philosophy seems to be permeating Black pop culture more and more. For example one of the biggest breakthroughs was the movie Black Panther which hit the cinema in 2018.

Afrofuturism is another way for the Black diaspora to process and express their experience, on a platform which has historically belonged to other communities. Caucasian and East Asian cultures have embraced Futurism through literature, anime or technological booms, and these have become the tokens of social privilege. Thus to dream of the future and to interact with visions and versions of realities is truly a sign of security. It moves beyond survival territory and, like the sky and stars synonymous with Futurism, it illuminates a clearer path for ascension.