“In order to find her reflection, culture and history Iris Kensmil followed the footsteps of fellow Dutchmen from Holland to Suriname to America to Ghana and Indonesia and back. She has given us a tangible trail of not only her but our own reflection, culture and history.”

The conclusion of Sasha Dees in her article on the Dutch/Surinamese artist Iris Kensmil.

Iris Kensmil

Iris Kensmil

DUTCH HISTORY REVISITED

Art – painting, writing and later photography, film and video – has always had an important role in documenting history. Indeed as the saying goes: “We cannot know where we’re going if we don’t know where we’ve come from.” However every nation encounters those moments in which heroic actions from a specific time and context put us to shame in another. What is heroic to one is an act of terrorism for another. History tells us that true history can only be found if we take all points of view and time and place into account. Art is an important tool in both documenting accepted histories and revisions to history. Art applied in this way can lead to reconstructions, change views and opinions and redefine history as we know it.

Iris Kensmil is an artist whose work does exactly that: Dutch history revisited.

Blackman!

What Is In Thy Bosom? Pluck it

Out – Is It Genius, Is It Talent

For Something? Let’s Have it.

(Marcus Garvey, 1934)

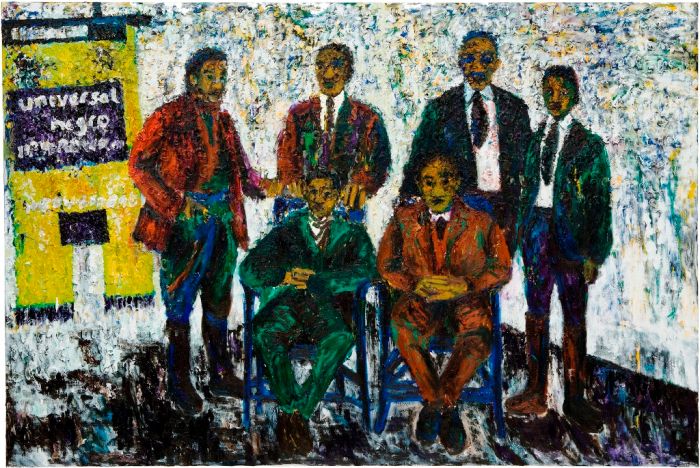

Universal Negro, 2008, 160 x 240 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: The Artist)

Universal Negro, 2008, 160 x 240 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: The Artist)

Iris Kensmil (1970) was born in the Netherlands and grew up in Paramaribo, Suriname (Dutch Guyana) till the age of 9 before moving to Amsterdam. As a teenager and student in Amsterdam there was always the nagging lack of a reflection of herself – the missing piece of Dutch culture and history that she knew should be there, in schools, in magazines and books, in songs, in museums, on television, in films.

Hope to see you soon, 2004, 800 x 800 cm / Original 200 x 180 cm Oil on canvas (Courtesy: Private Collector / De Key-Principaal/W139, Amsterdam)

Hope to see you soon, 2004, 800 x 800 cm / Original 200 x 180 cm Oil on canvas (Courtesy: Private Collector / De Key-Principaal/W139, Amsterdam)

The form of her work as a student and novice artist was abstract, colorful and text based. She focused on painting techniques and experimented with different color forms and surface, shaping and deepening her craft as a painter. Once she finished her art education at the Minerva Academy in Groningen, she gradually felt the need to research and find that reflection. Europe, which only got its first big waves of black immigrants in the 70s and 80s, proved to have little to nothing to offer.

Negroes (are okè), 2000, 64 x 142 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: Moniek Peters, Amsterdam)

Negroes (are okè), 2000, 64 x 142 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: Moniek Peters, Amsterdam)

What was available was a singular white point of view and imagery of Dutch history and culture. In turn she found refuge in the Nigerian author Ben Okri, the black emancipation movement in America and the Jamaican Marcus Garvey. Although highly successful with her abstract, text based works early on in her career, she decided to make a change. To cater to her own need to see her reflection, history and stories she started making figurative works.

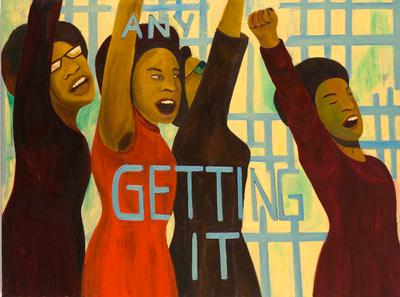

Any getting it, oil on canvas, 2004, 150 x 200 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: Museum Het Valkhof, Nijmegen)

Any getting it, oil on canvas, 2004, 150 x 200 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: Museum Het Valkhof, Nijmegen)

Similarly to Kerry James Marshall Iris Kensmil set out to exclusively paint black figures and faces to fill that same gap in the Netherlands that Marshall had felt before her in the USA. It was clear from the beginning that Iris Kensmil would not push herself into a victim role. Rather she is an emancipator. Lacking any inspiration for example in the Netherlands she explores and incorporates imagery from what she could find: the black emancipation movements in America.

A mural that includes images from the Black Panthers evoked controversy and heated discussions. White Dutch viewers complained about why they were confronted with a violent Black American history as that “has nothing to do with them”? With her works she incites and familiarizes her audiences about shielded history. Shared history, the Netherlands being the colonizers of New York (New Amsterdam) and a major trader in the human trafficking of Africans that took place in what in Dutch history is referred to as the ‘Golden Age’. The intense emotional reaction to works like the gallery wide mural ‘To determine the destiny’ portraying Black Panthers as heroic freedom fighters, only affirmed Iris Kensmil’s path.

To determine the destiny, (detail) 2007,300 x 1650 +300 x 750 cm, mural, pigment, casein, ink on paper (Courtesy: W139, Amsterdam)

To determine the destiny, (detail) 2007,300 x 1650 +300 x 750 cm, mural, pigment, casein, ink on paper (Courtesy: W139, Amsterdam)

In her research she uses all available resources to find new leads, information and inspiration. Music and lyrics are often her rewarding sources. Iris Kensmil is a big fan and an avid listener of reggae music. It was one of her favorite bands Burning Spear that led her to get to know and research the life and work of fellow Caribbean Marcus Garvey.

Marcus Garvey, 2008, 200 x 150 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: The Artist)

Marcus Garvey, 2008, 200 x 150 cm, oil on canvas (Courtesy: The Artist)

In the 2008 exhibit that followed, we could see a change in technique and choices in the series of paintings and drawings that came out of that research. The works are darker in color more serious. There’s a different way of investigating and exploring light. The paint is thick, the brush strokes short and brusque, there is a deepened intensity. Outside reactions to the series she made informed by Marcus Garvey continued to question the content of the work and the legitimacy of its political assertions. In his 2008 review of ‘Get Up Stand Up’ in Metropolis M, Hendrik Folkerts, wrote: “For instance, looking at Universal Negro or the artist’s Surinam background in comparison to her depiction of the African-American history, the question rises if this claim of universality is legitimate. Is there such a thing as the Negro and a universal black emancipation or should this struggle be defined in more specific cultural, national or even regional terms?”

Working on the Black American emancipation movement, Iris Kensmil starts to understand she can complement the lack she finds in Dutch history and in Dutch mainstream institutions by making art herself about this history based on research.

Plain and simple, Kensmil has a birthright to be an accepted part of the Western canon. It has been evident that this canon is in desperate need of completion. Kensmil‘s work seeks out the missing parts of our history and – rightfully so – incorporates them in our Western society and canon.

Sidonhopo, 2010, 465 x 840 cm, mural print (Courtesy: Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam)

Sidonhopo, 2010, 465 x 840 cm, mural print (Courtesy: Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam)

‘Sidonhopo’ (2010) is a work that was commissioned for ‘Monumentalism—History and National Identity in Contemporary Art’ at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Kensmil’s mural is a memorial to the Granmans (Captains), regional leaders of the Maroons in Suriname, at the time Dutch Guyana, part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. The black drawings of various Granmans hung over the mural based on forms and colors of pangi cloth designed by the Maroons. The mural shows part of a letter dating from 1926 from Granman Adjankoeso, grand chief of the Saramaccaners of Asidomphopo, written in Surinamese to the Secretary of the League of Nations (now United Nations) in Geneva. In the letter he expressed his joy over the end of World War I. The work presented and documented the Granmans as recognized and participating leaders in the League of Nations.

Out of History, 2013: Elisabeth Samson, Wilhelmina van Kelderman, Fabi Labi Beyman, oil on canvas, 3x 155×105 cm (Courtesy: Amsterdam Museum)

Out of History, 2013: Elisabeth Samson, Wilhelmina van Kelderman, Fabi Labi Beyman, oil on canvas, 3x 155×105 cm (Courtesy: Amsterdam Museum)

In 2013 The Amsterdam Museum presented ‘Golden Age, testing ground of our world’ in conjunction with the 150 years commemoration of the legal abolition of slavery in Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles. They commissioned Iris Kensmil to produce a new work. The work ‘Out of History’ consists of three life size paintings portraying people that took their lives in their own hands and in doing left their mark in 18th century Dutch History. Left to Right we see Elizabeth Samson (born Paramaribo, 1715 – died Paramaribo 21/22 April 1771), businesswoman, plantation owner and the first black woman in Suriname to marry a white man. Wilhelmina (Willemijn) Kelderman (no known date of birth nor passing) who paid the ransom for both herself and her son by writing a letter to plantation owner Engelbertus Kelderman March 14, 1795 (the original letter was found in British archives). Aukaner (Ndyuka) Gaanta Beiman Fabi Labi Dikan (Arabi) who signed a peace treaty with the Dutch Government in 1760 in which the Maroon communities in Eastern Suriname were declared free and independent. As photography was only invented around 1812-1831 there are no known portraits of either. The paintings come from the imagination of Iris Kensmil reflecting on the partly oral stories.

Displaced Persons: Belanda Hitam #2, 2014, 180 x 115, oil on canvas (Courtesy: The Artist)

Displaced Persons: Belanda Hitam #2, 2014, 180 x 115, oil on canvas (Courtesy: The Artist)

During an exchange project in Ghana, Iris Kensmil learned about Belanda Hitam ‘Black Dutchmen’, a group of three thousands Africans recruited between 1831 and 1872 for the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). These recruits from the then Dutch Gold Coast fought for the Dutch army together with European and native soldiers in the Java War against Prince Diponegoro. Most of the African recruits who were placed above the native soldiers and treated equal to their European soldiers stayed in Java, the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). Her research sparked her fascination with the path of people going from one continent to another in search for better lives. She got interested in the phenomena of displacement, which brought her back to herself and her own family history.

Displaced Persons: Boeroe #1, 2014, 180 x 115 cm oil on canvas (Courtesy: Haags Gemeentemuseum)

Displaced Persons: Boeroe #1, 2014, 180 x 115 cm oil on canvas (Courtesy: Haags Gemeentemuseum)

Iris Kensmil herself has a white, blue-eyed grandmother. Iris Kensmil started researching ‘Boeroes’ (Surinamese farmer of poor white Dutch ancestry who left Europe in search for a better life). She reads letters and documents of Boeroes who are visiting their family in Holland nowadays after living in Suriname for some generations. Like the story of a Boeroe calling various institutions in Groningen for a family matter. He was surprised by the lack of service and the outright crude treatment he received on the phone. When he finally managed to get an appointment he was shocked to realize from the embarrassment of the clerk and their apologies that they had given him the black treatment, now, still, in 21st century Europe. Based on the above research Iris Kensmil painted a first-generation Boeroe female based on an image she found on the internet as well as a portrait of a 21st century Boeroe male.

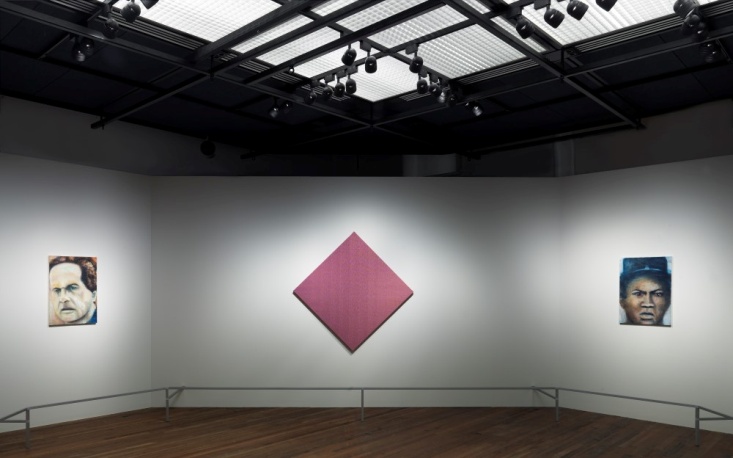

Shifting Colours 2014, Installation with Willem de Rooij (detail) Courtesy: Tropenmuseum/The Artist

Shifting Colours 2014, Installation with Willem de Rooij (detail) Courtesy: Tropenmuseum/The Artist

In her latest works on ‘Belanda Hitam’ and ‘Boeroes’ (both 2014) we see another change in her painting. It looks as if she has found some peace of mind. The paint is no longer thick and dark.The brush strokes are not brusque but soft yet firm. The light now seems to glow and reflect of the canvas. The bright colored surfaces are mature and subtle. Iris Kensmil seems to have outgrown the darker palette of the Dutch Golden Age.

In order to find her reflection, culture and history Iris Kensmil followed the footsteps of fellow Dutchmen from Holland to Suriname to America to Ghana and Indonesia and back. She has given us a tangible trail of not only her but our own reflection, culture and history.

Kensmil will participate in the first Contemporary Art Triennial of Suriname in Moengo, August 15 until September 20.

Iris Kensmil Negroes [are oke] – ISBN 978 90 76881 04

Sasha Dees is an international cultural producer and curator. Sasha is currently producing the art films: Witte Dieren (Simone Bennett, Russia) and Lorca/Casement Project (David Antonio Cruz, Ireland), is a guest curator for Centrum voor Beeldende Kunsten, visiting curator for Residency Unlimited and Art Omi (NY), juror for Akrai Residency (Italy), editor -with Rob Perrée- of the planned publication “I wonder if they’ll laugh when I’m dead” on Tirzo Martha (Curacao) and contributing writer to ARC Magazine and Africanah.org.