Is black art just a trend? “By putting the power of profit, the power of the gaze and the power of art into the hands of black communities, society can take this to the next level. Coupled with help from allies of all backgrounds then, and perhaps only then, can we say that black art transforms beyond a trend and into a sustainable force.”

Christabel Johanson tries to answer that ‘burning question’.

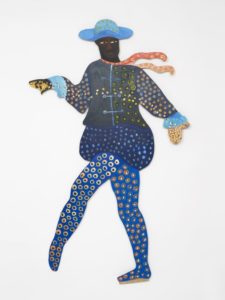

Lubaina Himid, The Dancing Master (detail of Naming the Money), 2004, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

Is Black Art just a trend?

Recently with events like the 1-54 Art Fair touring the globe through London, Marrakech and New York, it feels like contemporary black art has surfaced in people’s consciousness once again. Yet with all trends there is a time to wax and a time to wane. The pressing question is, is this only just a trend, or has black art proved itself an evergreen fixture in galleries and exhibitions?

As the Caribbean and African diaspora settle across the globe, in one sense it is easy to think that “black art” is no longer a novelty, a fashion statement or a tokenistic gesture. It is the natural integration of “the Other” in wider society. More so galleries – the formalised spaces of art – are embracing artists of color; from Asia as well as Africa and the West Indies. Yet in the everyday world that most people live in where there are still social inequalities, racism, gentrification and hate crimes which demonstrate some divide between people of color and the status quo. Therefore could the art world be in some way helping close these divides?

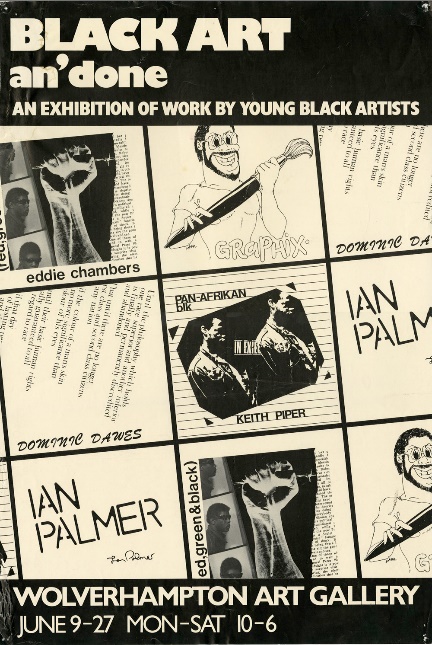

I spoke with Lisa Panting, co-founder and co-director of Hollybush Gardens, a gallery in Clerkenwell, London. According to Lisa their mission is to take selected artists and promote their practices to audiences (including collectors and institutional curators). This is achieved through writing about their work, exhibitions and of course art fairs. It is important to represent artists they believe in and as such they should be seen by the wider public. Interestingly one of the artists they represent is Claudette Johnson. Claudette was part of the BLK art group (in fact a founding member) who in the 1980s led the British charge of emerging black artists whose other members included Keith Piper, Eddie Chambers and Marlene Smith.

Poster of the BLK Art Group

So we see that even in recent history, black work has had periods of intense growth and interest. The legacy and achievements of the BLK art group were to break down racial barriers and challenge what institutions believed was popular and “good enough” to exhibit. So we have evidence of these periods leading to cohesion and general progress. Furthermore Lisa believes it would be a “fundamental misrepresentation to only show white artists, straight artists or male artists. It is really important to who we are and the contribution we wish to make to share work that reflects society’s aesthetic, social and political impulses and legacies”. As society evolves it’s political and aesthetic sensibilities then trends that pushed the limits of politics, beauty and discourse naturally make up parts of its new structure.

So Lisa what is your opinion that African/black art is getting “trendy” again? Do you think this is something that will remain or phase out?

We hope that a tipping point has been surpassed where the question is beyond trend and the question has more to do with the integrity of collections and exhibition programs. To NOT show black artists is again an omission that means that culture just isn’t being reflected properly in our galleries and institutions. The quality of work made by black artists also takes it beyond the question of merely reflecting our demographic. The talent means that the discussion also needs to become more sophisticated and be able to engage fully in the work artists are making. This means that art professionals who understand the work need to be working in museums, galleries and writing about it.

Do you see any indications on how interested audiences are for this type of work?

The possibility of black artists being on view in galleries changes the audience base. It shouldn’t seem strange to see more black audiences, but you realize just how white museum culture has been. It is a relief to see that changing.

Lubaina Himid, Naming the Money, 2014 (2017 version of the work)

Do you think art fairs like 1-54 have stimulated the interest and attention towards black art? Are you aware of any other fairs that represent black art?

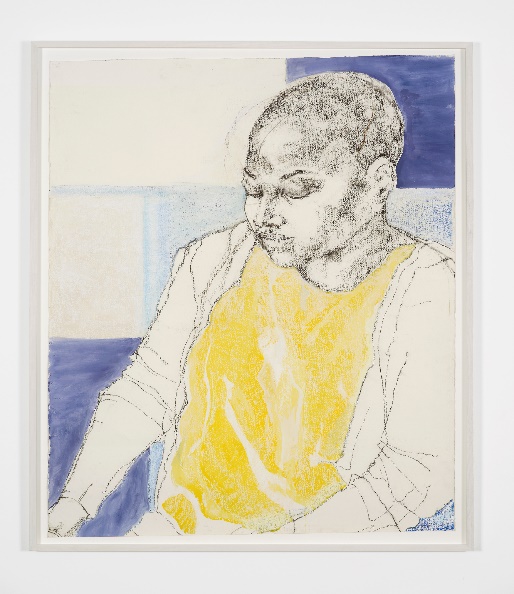

We participate in Frieze, Art Basel and sometimes other fairs. Claudette Johnson and Lubaina Himid whom we represent, whilst part of a diaspora, are also British and therefore it is important to showcase their work alongside their peers regardless of ethnicity and cultural belonging. It’s exciting to see conversations happen across a wide range of practices. We should be able to have a discussion about the quality of the line in the work of Claudette Johnson not only focus on her race or that of her subjects.

How do you think African/black art contributes to breaking down or changing barriers between black culture and the world?

When Lubaina Himid won the Turner Prize, the impact of being the first black woman to do so cannot be underestimated. Now young black girls can see this has been done and know it is possible. The mainstream success of British black female artists has been slower than their male counterparts, and this slight shift has changed the culture towards black female work. Of course more work has to be done, and in fact, what success does, is that it uncovers how deep divisions, racism and gatekeeping actually go – which just strengthens our resolve.

Lubaine Himid, Carrot Piece, 1985, Photo: Andy Keate, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

You have a gallery in London. Do you find this allows for your artists’ work to have a grassroots and an international platform?

Both. The artists have an international and local platform – as we travel to international art fairs our program reaches out beyond the physicality of the gallery space.

Are there any upcoming exhibits or events that represent black art you are excited about?

We are excited by Lubaina Himid’s solo show at the New Museum in June, Claudette Johnson at Modern Art Oxford from artists we represent. Helen Cammock at Whitechapel Art Gallery. There will be a show about the Caribbean diaspora at Tate Britain in the summer. There are very many exhibitions happening this year that will showcase works by artists we love, whether we work with them or not, and that I can’t list them on one hand can only be a step forward.

Claudette Johnson, Seated Figure, 2017, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

Claudette Johnson, Standing Figure with African Masks, 2018, photo: Andy Keate, courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

Do you have any predictions of the general development of African/black art in the future?

We can only hope that some of the gains and visibility now mean that galleries in general are not afraid of showing black artists and may in fact feel like it is no longer acceptable to only show white artists. Of course the art market plays a role and with South Africa developing a gallery scene there are conversations happening across different centers and maybe a decentralizing is beginning to happen that means it isn’t only about London, New York and Berlin – but Bogata, Cape Town, Kingston, Lagos, and other centers that are part of a wider distribution of art and ideas.

***

Certainly society feels like it is progressing towards an integrated model of art; more about the work itself rather than the “black and white” divide. However whilst inequalities still exist, we cannot totally forget the importance of representing artists from Caribbean and African backgrounds. Whilst this may be more and more the norm rather than a trend, the real litmus test as to whether black art will phase out relies on empowerment from a grassroots level.

By cultivating this in typical black spaces, like the West Indies or Africa, what will emerge is an A-Z production of black work. Through the decades, the conversations around “trends” and what is “trendy” has been promoted and demoted by mainly white people with the power to do so. By putting the power of profit, the power of the gaze and the power of art into the hands of black communities, society can take this to the next level. Coupled with help from allies of all backgrounds then, and perhaps only then, can we say that black art transforms beyond a trend and into a sustainable force.