I hope that this artwork throws light on yet another aspect of global capital cycles that should be governed by fairer international Mineral Rights laws. Because this predatory mineral exploitation is a wave of neo-colonialism that could be curbed by more ethical governance internationally and not left to a few African leaders who do sign away rights for a pittance without conceiving of real value.

Candice Allison interviews Jeannette Unite

Measuring Modernity.

Mining as a point of departure

An interview with Jeannette Unite

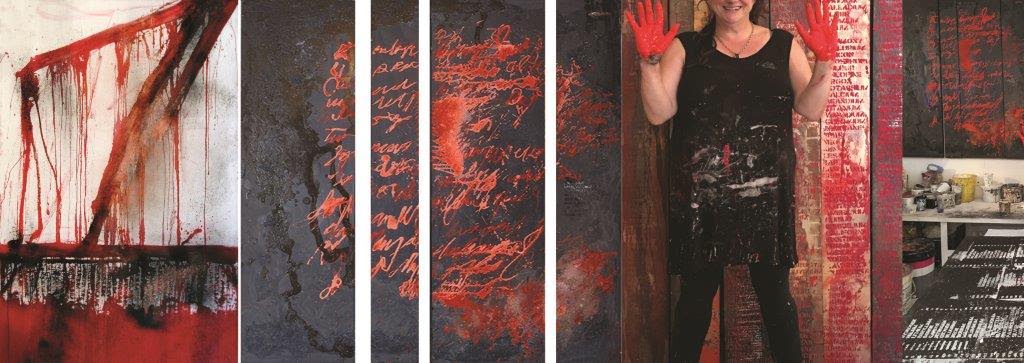

Jeannette Unite was born in South Africa in 1964, where she still lives and works. She is a mixed media visual artist who is immersed in the materiality of the art making process, whether it is using her own hand-made chalk-based pastels with mineral oxides, or using similar metal oxides in paintings, drawings or prints. She uses images, information and metaphors from mining as a point of departure for her reflections on her own personal journeys. Throughout her twenty year career, she has travelled to mining and industrial sites for material samples, and to research and photographically record evidence of the residual remains of power, industrialization and neo-colonialism on the African landscape. She completed an MA Fine Art at the Michaelis School of Art, University of Cape Town in 2014, and her BA Fine Art at the same institution in 1986.

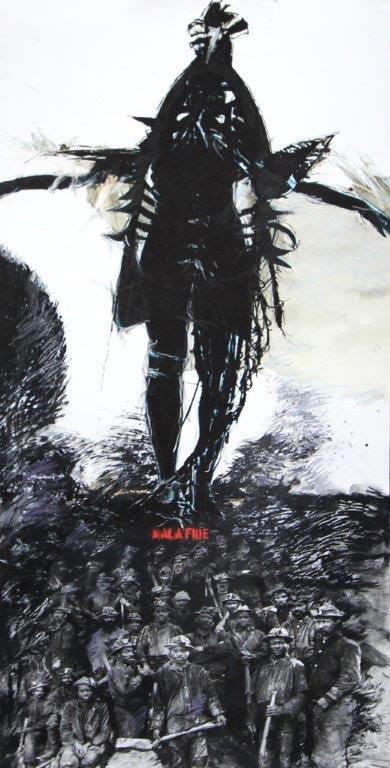

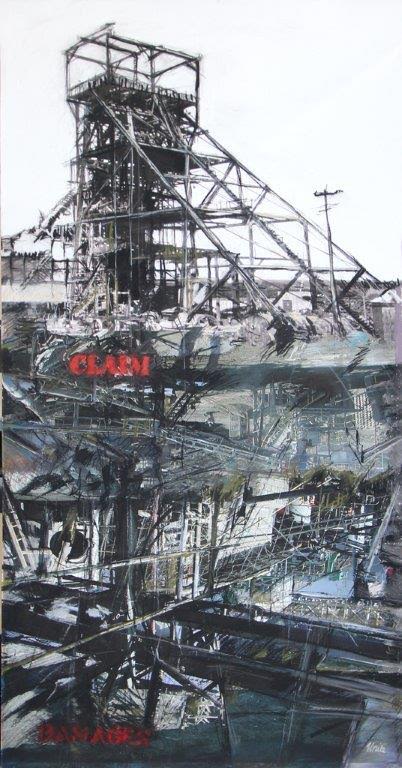

Between the Stratum of Trauma and Violence.

Conversations with Unite cannot be digested in one sitting. The sheer magnitude of ideas and the depth of her knowledge that she passionately and candidly shares need to be taken home, savored, and returned to, when the palate has been cleansed and is ready to appreciate the next course. Her studio is a physical and visual manifestation of her thought processes. Like stepping into the most sumptuous French patisserie, visitors are met with a smorgasbord of color, texture, raw materials, giant pastels, paints, glass jars and vials, geological and scientific instruments, and artworks lining the walls in every shade of the color spectrum – rich blues, greens, oranges, golds, reds and yellows. The surfaces of her paintings are thick, tactile and gritty. Her drawings are dark, loose, and gestural. There is an inherent anxiety to her mark making. Her source material is a personal archive of hundreds of images taken over the course of more than two decades; of the mines, mining processes, waste products and end-user goods, of almost every extractable mineral resource found across the African continent. While her concern is with issues around human and environmental wreckage of the mining industry, she also approaches her work with a deeply personal understanding of her complicit role in the mining chain of production. Her research and work is a reminder that we are all part of the market that drives the demand for mineral resources.

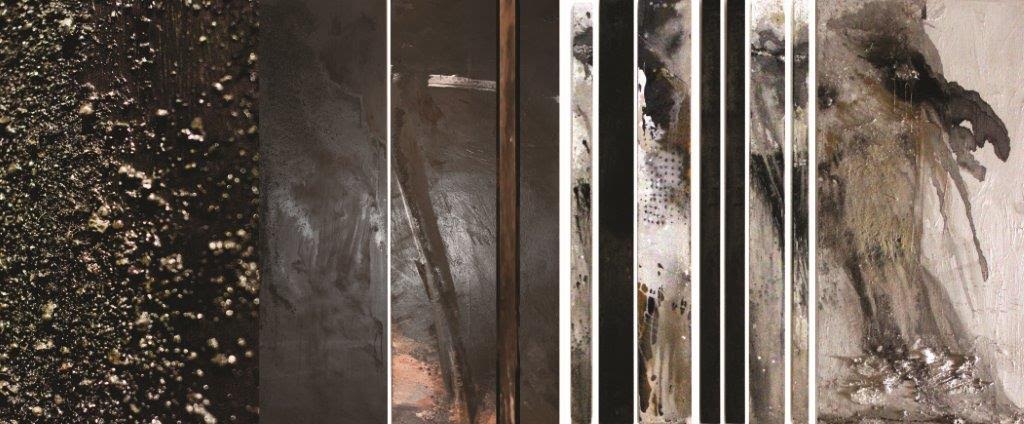

Measuring Modernity (Copper from Namaqualand).

This interview is a compilation of numerous conversations, emails and telephone calls that took place in June 2017. All images courtesy of the artist.

CA: Can you start by telling me about what you are busy making in your studio at the moment?

JU: I have mixed some paint, made with mine dump detritus, metal oxides and matter from smelters and industrial sites, for continuing to paint on various ongoing series that include the ‘Geo-Seam’: bar-code mineral lode panels echoing strata; ‘Measuring Modernity’ which are 30x30cm squares; and a series entitled ‘ERF/ PLOT’ referencing industrial sites and half-finished drawings and aerial photographs that had been used as teaching aids in the Department of Earth Sciences at Oxford University for a grid installation that is about land legislation.

CA: You have spoken a great deal about the importance of the materials that you use in your work. Where do your materials come from, how do you work with them, and how much of your practice is informed by the material you are using?

JU: When I was living on West Coast Diamond mines in the 1990s a geologist told me that “titanium is diamondiferous”. I realised that I am an end-user of mining because titanium was also in my paint tubes.

I had already been making my own paint with pigments, marble dust and acrylic base since undergraduate years under Professor Kevin Atkinson, who had shared this method with his students. It seemed a logical concept to use material I had ‘mined’ myself from mines, quarries and industrial sites that contain residues of metal ores; materials that also represent stories and the experience of the places they come from. I use the material itself to convey the all-encompassing redness of an iron ore mine and how different this is from the verdigris of a copper mine; or the blue-grey on a diamond separation plant where the volcanic ore from the Kimberlitic pipes is referred to as “blue ground”.

By collecting material directly from platinum, diamond, gold, copper, zinc, zirconium, iron, coal mines, chalk and kaolin quarries and mixing these into a stabilising archival polymer acrylic emulsion – the medium becomes the message. When I visit the mines, smelters and processing plants I also take photographs and interact with the geologists to glean more information. The material becomes a means to tell the story.

Gea – Seam (Johannesburg Gold)

CA: The recipes that you use for making your materials, do they allow room for experimentation or have you worked out a set of rules for each recipe?

JU: I worked in glass for a decade – and there were more reactions in glass kilns in furnace-high temperatures turning mine detritus and metals back to flowing magma at times. Especially if we used colours and fluxes (mostly toxic) like lithium, lead, for serendipitous surprises and reactions.

I was guided by the maverick ceramic ‘alchemist’ genius of Jo Faragher who died in 2007, possibly from over-exposure to all the fumes from his glazes. As an ex-underground mining engineer he understood and shared not only the chemistry of the minerals we were working with, but also the geological subterranean position and socio-political rubric behind extraction of those materials.

But I am still surprised when a new mineral I play with in paint almost curdles alkalines with acidic or ‘creeps’ and separates in an unusual way. New combinations always make for interesting surprises.

CA: In contrast, you have a very loose, abstract approach to your painting. Can you tell me about the process, or the journey, that brought you to your distinctive aesthetic style?

JU: I am a modernist at heart – and loved the post-painterly abstractionists. After I discovered the strange forms in mining (I find the formal engineering angles and masses of metal that move landscapes mouth-watering wonderful), I worked on non-representational large works before I started directly referencing the mining Industry. I split the works to define ‘Visual Sentences’ – supports that are made up before I work. The way I paint is very gestural; the medium is applied liberally on a paved area that allows the wet viscous paint to move and run with gravity.

Claim Damages – the Subterraneam

CA: Do you tend to visualize in advance? Do you have a set image of what you want to create or is it purely about the materials that you want to bring to the fore?

JU: The vast collection of images sourced from my journeys to mines and museum archives are a starting point, and often times it is the material itself that guides the works. The drawings involve more planning as they are recognisable.

CA: You are clearly knowledgeable about the scientific and geological side of mining, and from what I understand a large part of your practice is research based. What are you researching now?

Stock Exchange of Minerals

JU: Apart from finishing the book COMPLICIT GEOGRAPHIES, I have been compiling a list of who owns all the mines in all the countries in Africa for a multi-panelled artwork with the working title “Who Owns Africa”. I am hoping that the ownership of the continent’s mineral resources by organisations outside Africa will be seen at a glance.

My intention is to stencil transfer the list of mines, with paint made with the relevant mined matter; so to use titanium, platinum, iron or gold mine dust if that is the main ‘product’ of the mine operation, alongside owners listed on Toronto, New York, London, Hong Kong, Australian stock exchanges or found in mining media or from my own travels and experience. Despite having arranged access to various lists through contacts in mining and geology internationally, the information is not easily available, or at least, no single existing list of African Mines is comprehensive, by their own admission.

CA: Were you surprised by this lack of transparency in the mining industry? For me, as a South African, and I am sure I am not alone in feeling this way, it just seems that mining companies and the mining industry itself is Evil with a capital E. Any kind of mineral extraction, it seems, is mired in secrecy, corruption, human rights abuses, and environmental destruction.

JU: I shouldn’t have been as surprised as I have been that there is an astounding lack of transparency around resource wealth on the continent. The lack of information enables exploitation and plunder. The corporations have a term ‘The Resource Curse’; a construct used to describe why people who live above valuable mineral commodities are automatically poor. This is in my opinion a worse situation for African countries than the original wave of Colonialism. Resource rich countries on Africa’s continent are left with environmental repercussions and water contamination from extraction without the financial benefits of their own commodity’s values. Copper from Zambia is sold at artificially reduced prices to avoid tax to foreign based companies who resell it to other companies owned by themselves, resulting in countries like Switzerland which has ZERO copper deposits or copper mines, exporting many times more tonnes of copper than Zambia.

One of the solutions for neo-colonialism would be if the real price of ore is paid to the country of extraction, calculated to include labour, environment, natural energy and electricity to create the deposit, it would be a thousand times more expensive. And humans would be that much more careful with manufacturing built-in-obsolescence and waste.

I hope that this artwork throws light on yet another aspect of global capital cycles that should be governed by fairer international Mineral Rights laws. Because this predatory mineral exploitation is a wave of neo-colonialism that could be curbed by more ethical governance internationally and not left to a few African leaders who do sign away rights for a pittance without conceiving of real value.

Complicit – Red Handed

CA: Well I look forward to seeing it when it’s finished. Does all your work reflect on the social and political consequences of mining?

JU: We are all complicit in mining. I want to get that message across through mined material.

Also by using images, maps, surveillance, measuring and reference legal systems that define ownership. As humans we are entirely dependent on Earth and minerals for tools and technologies. All wealth is created from Earth, both metal deposits in the subterranean and Real Estate on the surface.

Modern systems and knowledge are managed on a grid. The land is measured, divided and allocated via Title Deed and Mineral Rights. Laws of land are traceable back to Sumerian clay tablets ‘cast-in-stone’ and are core to the systems of modernity.

CA: This is going back a few years for you, but the other work I was interested in hearing about is ‘Paradox of Plenty’. Photography seems to be an important resource for you, and looking through image after image of mines and headgears, I can’t help thinking of other photographers like David Goldblatt, and even more so Bernd and Hilla Becher’s ‘typologies’. I think Goldblatt was trying to document a social phenomenon in South Africa, of cheap labor and cheap lives; while the Becher’s were feverishly documenting the sheer scale and aesthetic standardization of the industrial revolution. What do your photographic archives represent for you?

JU: Strangely I landed on the Headgear series when I was working on an exhibition for the old State Archives in 2008 and was faced with finding a theme about mining in the 45 kilometres of records. I combined headgears from the State Archives with my own travels to mines. Only after this 2008 exhibition ‘Remembering the Future’ – was I directed to the Becher’s – whose ‘typologies’ I love.

I take a lot of stop frames of the industrial sites I visit to convey a sense of being there. I want to take you to these strange almost other world sci-fi spaces, so I take multiple frames that work in photographic animated gifs that I use in the exhibition installations.

CA: There is a sense of repetition in all your work. You don’t ever just make one drawing of one thing, or one painting using one material. When do you decide that you have completely exhausted an idea or a material?

JU: I like working in series, to complete a sequence of related ideas. When I find a scale and format that best conveys works like ‘The Paradox of Plenty’ and ‘Headgears’, I will keep working in that same format, creating enormous grids or barcodes that can be continuously added to or taken away from.

I intentionally work vertically, more than horizontally, even though landscape artworks are traditionally literally in a ‘landscape’ format. Partially because my concern is about how humans interact with Earth.

Geo – Seam (Platinum Titanium Liminite)

CA: Tell me more about COMPLICIT GEOGRAPHIES? What is the impetus behind the book and what bodies of work will it include?

JU: In COMPLICIT GEOGRAPHIES I hope to show global cycles of extraction, manufacture, consumption and waste.

I have shifted from being extremely critical of mining when I started living on mines in the 1990s, and working as an artist. But I am not judgemental, I realise we are all involved, our activities make us complicit because we consume. From Stone Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age, we use ‘stuff’ that is mined to manufacture tools. Everything we use comes from mining or agriculture. And because we consume, we drive the market and that drives mining and resource extraction.

I also want to highlight that we must be better stewards of this marvellous planet that is our only home.

Candice Allison is a Cape Town based curator and writer. She is currently Curator of The New Church Museum Collection. She holds a Masters with Distinction in Curating Contemporary Design from Kingston University, London and a BA Honors in History of Art and English Literature from the University of Pretoria.