Like a true sadist, Kemang Wa Lehulere’s show disavows any grand finale by always opening up “the end.” We leave the show content, filled but not certain with what exactly.

Athi Mongezeleli Joja on Kemang Wa Lehulere.

Red Winter, 2016.

A KNIFE EATS AT HOME

On a recent exhibition of Kemang Wa Lehulere at Stevenson in Cape Town

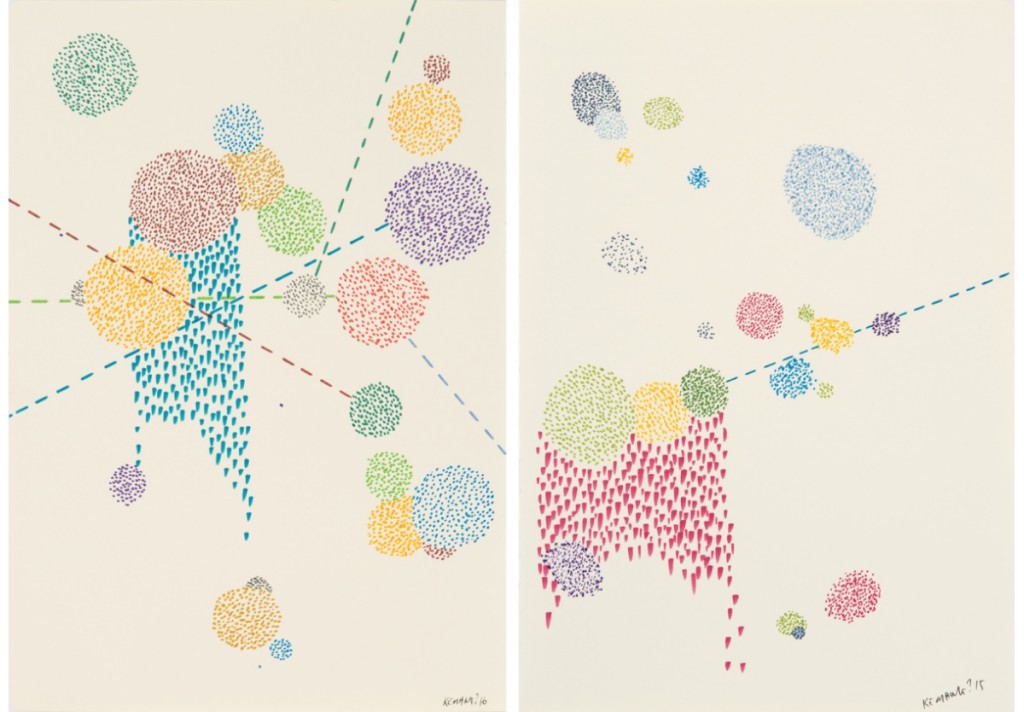

‘The Knife Eats at Home’ is Kemang Wa Lehulere’s current show at Stevenson gallery, Johannesburg, is first, a festival of color. This is so because the show presents a startling tincture of color nearly unprecedented in Wa Lehulere’s rapidly fledgling oeuvre. We see this reluctant or minimalist palette present in his most prominent works, where color fleets through or appears almost by sheer accident of its inevitability.

Monument to Lost time, 2016.

Not to say that it currently bleeds uncontrollably but to that it blends contortedly with graceful and furtive charisma. A taciturn palette bouncing off from the jumble of salvaged objects and the manipulated gallery walls, as if it were musically composed. On another side, paradoxically, color is the constitutive underside of Wa Lehulere’s oeuvre – as an embedded implicit reference talking through his body, history and objects.

The Messengers or The Knofe Eats at Home, 2016.

Where previously color appeared with relative and reticent chromaticity, it now jolts with authority and authorship. This is not achieved merely by its pure kaleidoscopic prominence but also by its considerably self-conscious aesthetic utility in the show. We could just talk of the palette and nothing else but the show, despite its eclecticism, without clutter, gestures to something more socially pressing.

X, Y, Z, 2016.

The gap between play and responsibility, or difference between a recreational space and the trenches that emerge are never neatly wedged. But our loss of the innocence of play doesn’t guarantee the disappearance of the juvenility in which our society perpetually lodges blacks into. The tension between beautiful things and the ugly situation – between pleasure and violence – is implicit but also pervasive here. We can get caught and trapped in the pleasure conferred by objects, and inadvertently run the risk of not hearing its speech.

Kisses from the future or Days to come, 2016.

(detail)

The artist quite beautifully plays the conflicts between the thingliness of things – their recyclability from one semiotic prescription to another in the symbolic world, and the capacity of objects as such to render new meanings and aesthetic sensibility. To some extent this is what con-temporaneity means, the coming together of times embodied in their discrepant representations. There’s a heavy objectness in the show, pervasive from sculptural pieces, to the neatly framed drawings and even the very aggregated installations and less ephemeral works that previously dominated. More interestingly, with the turn to more sculptural pieces, the idea of dematerialized objects, which the artist is latently associated with, appears dramatically farce.

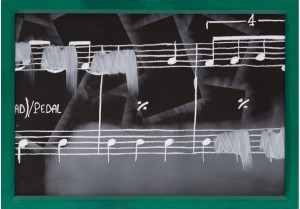

Broken Light 3, 2016.

Cosmic Interluded Orbit, 2016.

Things are never quite done away with or forgotten in Wa Lehulere’s work, but even when they are brought back, they are never simply and clearly revealed. They reappear with parts of them missing, deliberately erased or insinuated. Those could be stories, sketches, random thoughts, drawing marks, objects – motifs returning without promises, except the promise of their return. The school desks have returned as aeroplanes, hair as painting material, what was previously a sketch is now part of a drawing series or large size piece and even his porcelain dogs have returned in pieces. Even when things appear for the first time, we don’t lose “the return” only, it becomes the motif through repetition like we see in his intriguing sound installation, suitably titled, ‘One Is Too Many, a Thousand Will Never Be Enough’. This makes Kemang’s work a motivation to the return of formal reading of art, which as some argue, is either missing altogether or trapped in the old investment in auto telic reading.

Galaxy in Gugulethu 1, 2016.

And although there might not be clutter in Kemang’s aesthetic eclecticism, we never too clear about what it really wants to leave behind except traces that lead us between somewhere and nowhere. Perhaps this decision is deliberate. Occupying two spaces; both the main gallery and the new space upstairs, we can still discern disorderliness in the incoherent or lack of a conceptual thread that binds his pretty objects. At times it feels like one has been writing the same endless review of preparatory shows, but keep shifting words around.

Where there is aesthetic consistency in the body of work, and each piece speaks with clear individuality, the articulation of the conceptual project appears almost interrupted, disparate, even muted. A body present but disembowelled. A beautiful home erect but not assembled. This refusal of the purposive end, the denouement that gives us satisfaction, is stolen away almost consistently. Like a true sadist, Kemang Wa Lehulere’s show disavows any grand finale by always opening up “the end.” We leave the show content, filled but not certain with what exactly.

Until July 15 in Stevensen Gallery Johannesburg

Courtesy Stevenson Gallery