Much like the work of authors, these are character studies of timeless protagonists who never existed but can have as much impact on audiences as literary heroes. Interestingly Yaidom-Boakye is also a writer, so she understands how to structure a story. Her pictures are a narrative without words.

Christabel Johanson on the British-Ghanaian artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

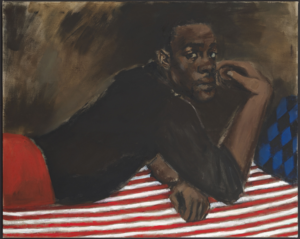

Vigil For A Horseman (detail), 2017

First published: May 6, 2020

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye

I write about the things I can’t paint and paint the things I can’t write about

From the 20th May until 31st August Tate Britain is exhibiting Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Fly in League with the Night. The exhibit will bring around 80 of Yaidom-Boakye’s paintings since 2003; making it the most thorough portfolio of her work to date.

*

The artist’s pictures have captured viewer’s imaginations because the people she presents are all fictitious. As they are not real people we cannot describe the pieces as ‘portraits’ but they are as enigmatic and captivating as any portrait of a real person would be.

A Passion Like No Other, 2012

The lauded artist has been a Future Generation Art Prize winner and was selected for the 55th Venice Biennale. Her success is in part from the textured compositions which emanate from her imagination. They are said to exist apart from a contemporary setting or time, and can be taken out of context which invites viewers to interpret the figures for themselves.

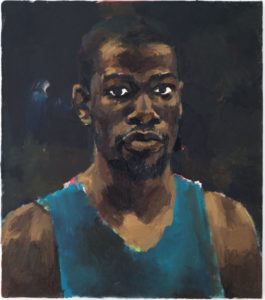

Leave A Brick Under The Maple, 2015

The Tate describes the British-Ghanaian’s work as “Often painted in spontaneous and instinctive bursts…Her paintings are coupled with poetic titles, such as Tie the Temptress to the Trojan 2016 and To Improvise a Mountain 2018. Writing is central to Yiadom-Boakye’s artistic practice, as she has explained “I write about the things I can’t paint and paint the things I can’t write about”.

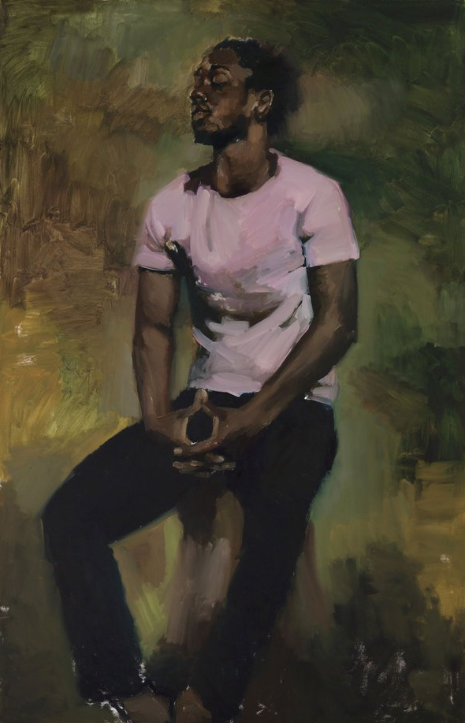

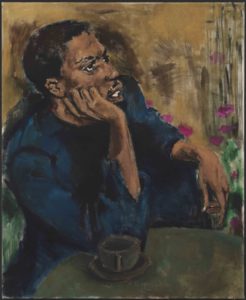

Coterie Of Questions , 2015

So it appears that these context-less apparitions only exist within the framework of Yiadom-Boakye’s mind, dispersed out for our understanding. They are an expression of feelings, thoughts, moods she cannot articulate in words save for their titles. Therefore the power of interpretation is at work here. In the above picture entitled Coterie of Questions we see a young black man sitting with his hands clasped in a pondering position. His eyes are shut contemplatively. The viewer could apply their own reading of the scene. Is he blissfully meditating? Does he have a burning question he needs to think over? Are the questions he ponders shared or particular to him?

*

The artist says that she paints “bits and pieces” of life, which she often compares to a scrapbook. Drawings, old photographs and fragments of memories are the elements of the scrapbook and combine to form her oeuvre. She says the pieces are completed within a day without further improvement because her attention is on “the actual nature of the painting itself and what that does to the subject rather than what the subject does to the painting”. With regards to the form, she confesses that there is “something about nature, about the senses, about history, that is all encapsulated in oil paint … It feels closer to the body … it forms a skin. It moves like skin when you paint”. The cloaking garb of oil paint forms that intimacy. It is obvious that Yaidom-Boakye wants to form a relationship between the art work and the viewer and, in this way breathe life into the subjects of her work. The history, the storytelling and the particular world evoked within each unique piece is the all the context it needs to be read in.

Greenhouse Fantasies, 2014

The subjects of her paintings are black women and men. We ask ourselves how relevant is the race of these pretend people? “People are tempted to politicize the fact that I paint black figures, and the complexity of this is an essential part of the work. But my starting point is always the language of painting itself and how that relates to the subject matter”. So what is the language of her paintings? She often uses dark and muted tones to create a broody atmosphere. Her subjects sit or pose in relaxed or static positions. Shoes are usually off or not shown so that the work doesn’t age or reveal any decade of fashion. These factors attribute to the relatability of the pictures, and by extension perhaps the relatability of the figures for black and non-black audiences. Much like the work of authors, these are character studies of timeless protagonists who never existed but can have as much impact on audiences as literary heroes. Interestingly Yaidom-Boakye is also a writer, so she understands how to structure a story. Her pictures are a narrative without words.

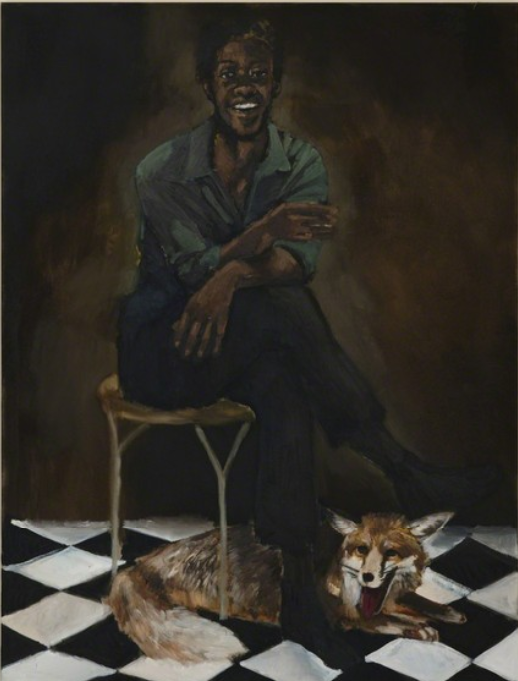

Black Allegiance To The Cunning, 2018

In the above image, the smile on his face subtly matches the fox’s grin. His casual pose coupled with the animal by his feet creates a cool and languid appeal. The title Black allegiance to the Cunning says all it needs to complement the character’s imagery. The nuances and the symbolism are expressed in the same way a novelist might ‘paint’ a feeling or mood in a book. Instead of words, Yaidom-Boakye articulates this expression with her pictures in a beguiling manner.

*

This also gives us an idea about identity and race in the same way numerous white characters have been represented in multi-media. Visibility in her work is more important than drama, and it breaks through the glass ceiling in a different and disarming way. The people ‘belong’ in their space and more so they are given the space to exist as they are. There is no immediate threat or hardship and no encroachment by white figures. Similarities can be made to John Singer Sargent or Edouard Manet’s catalogue of models. Yaidom-Boakye’s black figures are the alternative to these white characters who traditionally take up gallery space. The irony here is that black representation is advocated for by non-existent black people.

A Passion Like No Other, 2012

Storytelling is an innately voyeuristic activity because it lures the audience into its narrative. By identifying with its protagonist viewers are made to relate to their plight, their cause or their motivations. These figures become a reflection of everyday life; they are everyday people. The figures are supposed to evoke the senses in a three-dimensional way through the composition, colours, poses and most importantly the texture of emotions presented. The characters achieve a state of peace and calmness which is not traditionally afforded to a black body. Yiadom-Boakye also once said that “they’re all black because, in my view, if I was painting white people that would be very strange, because I’m not white. This seems to make more sense in terms of a sense of normality”. When white artists depict white bodies there is perhaps a subconscious acceptance that this is the norm, that this is the default representation. So by applying this logic to her own work, the artist side-steps the politics of black representation without removing the value of it.

Brothers To A Garden, 2017

“One of the things I always destroy in the work is anyone that I think looks passive. In part, this is because they’re black, and in part because I don’t want them to like anyone has taken anything from them. I don’t want them to be victimized basically, or to look that way. It’s as much about avoiding certain tropes in the work as anything else”. By avoiding the victimisation of the black body, perhaps Yaidom-Boakye pulls off a style of realism which asserts her own value to the ongoing narrative of black bodies in art. For her the black body can cease to be a spectacle, a token figure or a subversive message. Therefore her message of normality, relatability and tranquillity adds a sense of peace to a typically animated dialogue on race.